|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: HIC 6.1: The Chimariko

Item page — this may be a chapter or subsection of a larger work. Click on link to access entire piece.

Earthdate 2005-11-12

The Chimariko were one of the smallest distinct tribes in one of the smallest countries in America. They are now known to be an offshoot from the large and scattered Hokan stock, but as long as they passed as an independent family they and the Esselen served ethnologists as extreme examples of the degree to which aboriginal speech diversification had been carried in California.

Two related and equally minute nations were neighbors of the Chimariko: the New River Shasta and the Konomihu. The language of these clearly shows them to be offshoots from the Shasta. But Chimariko is so different from both, and from Shasta as well, that it must be reckoned as a branch of equal age and independence as Shasta, which deviated from the original Hokan stem in very ancient times. It seems likely that Chimariko has preserved its words and constructions as near their original form as any Hokan language; better than Shasta, which is much altered, or Pomo, which is worn down.

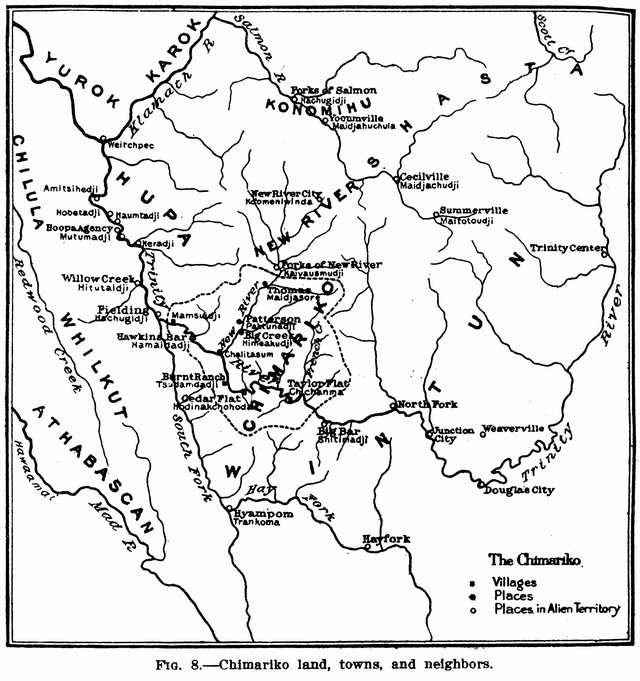

The entire territory of the Chimariko in historic times was a 20-mile stretch of the canyon of Trinity River from above the mouth of South Fork to French Creek (Fig. 8). Here lay their half dozen hamlets, Tsudamdadji at Burnt Ranch being the largest. In 1849 the whole population of the Chimariko was perhaps 250. In 1906 there remained a toothless old woman and a crazy old man. Except for a few mixed bloods, the tribe is now utterly extinct.

The details of the fighting between the Chimariko and the miners in the sixties of the last century have not been recorded, and perhaps well so; but the struggle must have been bitter and was evidently the chief cause of the rapid diminution of the little tribe.

Since known to the Americans, the Chimariko have been hostile to the Hupa downstream, but friendly with the Wintun upriver from them. Yet their location, with reference to that of the latter people and the other Penutians, makes it possible that at some former time the Chimariko were crowded down the Trinity River by these same Wintun.

The Chimariko called themselves Chimariko or Chimaliko, from chimar, person. The Hupa they called Hichhu; the Wintun, Pachhuai — perhaps from pachhu, “willow”; the Konomihu, Hunomichu — possibly from hunoi-da, “north”; the Hyampom Wintun, Maitro-ktada — from maitra, “flat, river bench”; the Wiyot, Aka-traiduwa-ktada — perhaps from aka, “water.” Djalitasum was New River, probably so called from a spot at its mouth. They translated into their own language the names of the Hupa villages, which indicates that distrust and enmity did not suppress all intercourse or intermarriage. Takimitlding, the “acorn-feast-place,” they called Hopetadji, from hopeu, “acorn soup”; Medilding, “boat-place,” was Mutuma-dji, from mutuma, “canoe.” The Hupa knew the Chimariko as Tl'omitta-hoi.

The customs of the Chimariko were patterned after those of the Yurok and Hupa in the degree that a poor man's habits may imitate those of his more prosperous neighbor. Their river was too small and rough for canoes, so they waded or swam it. They used Vancouver Island dentalium shells for money, when they could get them; but were scarcely wealthy enough to acquire slaves, and too few to hold or sell fishing places as individual property. Their dress and tattooing were those of the downstream tribes; their basketry was similar, but the specializations and refinements of industry of the Hupa, the soapstone dishes, wooden trunks, curved stone-handled adzes, elaborately carved soup stirrers and spoons, and rod armor, they went without, except as sporadic pieces might reach them in barter.

With all their rudeness they had, however, the outlook on life of the other northwestern tribes — a sort of poor relation's pride. Thus they would not touch the grasshoppers and angleworms which are sufficiently nutritious to commend themselves as food to the unsophisticated Wintun and other tribes farther inland, but which the prouder Hupa and Yurok disdained. The only custom in which the Chimariko are known to have followed Wintun instead of Hupa precedent — though there may have been other instances which have not been recorded — was their manner of playing the guessing game, in which they hid a single short stick or bone in one of two bundles of grass, instead of mingling one marked rod among 50 unmarked ones.

The Chimariko house illustrates their imperfect carrying out of the completer civilization of their neighbors. It had walls of vertical slabs, a ridgepole, and a laid roof with no earth covering. These points show it to be descended from the same fundamental type of all wood dwelling which prevails, in gradually simplifying form, from Alaska to the Yurok. But walls and roof were of fir bark instead of split planks. The length was 4 or 5 yards as against 7 on the Klamath River, the central excavation correspondingly shallow. The corners were rounded. A draft hole and food passage broke the wall opposite the door where the Yurok or Hupa would only take out a corpse. And the single ridgepole gave only two pitches to the roof — a construction known also to the lower tribes, but officially designated by them as marking the “poor man's house,” the superior width of their normal dwelling requiring two ridge poles and three slants of roof.

Chimariko religion was a similar abridged copy. Sickness, and, on the other hand, the medicine woman's power to cure it, were caused by the presence in the body of “pains,” small double-pointed animate objects, which disappeared in the extracting doctor's palm. The fast and uncleanness after contact with the dead lasted five days, and had to be washed away. Such more elementary beliefs and ritual practices for the individual the Chimariko shared with the other northwestern tribes. But the great national dances of the Yurok, Karok, and Hupa, held at spots hallowed by myth, colored by songs of a distinctive character, dignified by the display of treasures of native wealth, and connected with sacred first-fruit or even world-renewal ceremonies, these more momentous rituals the Chimariko lacked even the pretense of, nor did they often visit their neighbors to see them. They were a little people in its declining old age when civilization found and cut them off.

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12

1 comments: (End)