|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: 2004-01-25 Archive

Earthdate 2004-01-30

Far-thinker physicist Freeman Dyson, in his intriguing book Infinite in All Directions, describes the profound impact in history of a very simple technology: 1

The technologies which have had the most profound effects on human life are usually simple. A good example of a simple technology with profound historical consequences is hay. Nobody knows who invented hay, the idea of cutting grass in the autumn and storing it in large enough quantities to keep horses and cows alive through the winter. All we know is that the technology of hay was unknown to the Roman Empire but was known to every village of medieval Europe. Like many other crucially important technologies, hay emerged anonymously during the so-called Dark Ages. According the Hay Theory of History, the invention of hay was the decisive event which moved the center of gravity of urban civilization from the Mediterranean basin to Northern and Western Europe. The Roman Empire did not need hay because in a Mediterranean climate the grass grows well enough in winter for animals to graze. North of the Alps, great cities dependent on horses and oxen for motive power could not exist without hay. So it was hay that allowed populations to grow and civilizations to flourish among the forests of Northern Europe. Hay moved the greatness of Rome to Paris and London, and later to Berlin and Moscow and New York.

1

Freeman Dyson, Infinite in All Directions: Gifford Lectures given at Aberdeen, Scotland: April-November 1985, 1988, Harper & Row, New York; Library of Congress catalog no. Q175.3.D97 1988;

UPDATE: 2004-02-01 10:45 UT: Simple Tech II posted.

Impearls: 2004-01-25 Archive

Earthdate 2004-01-17

|

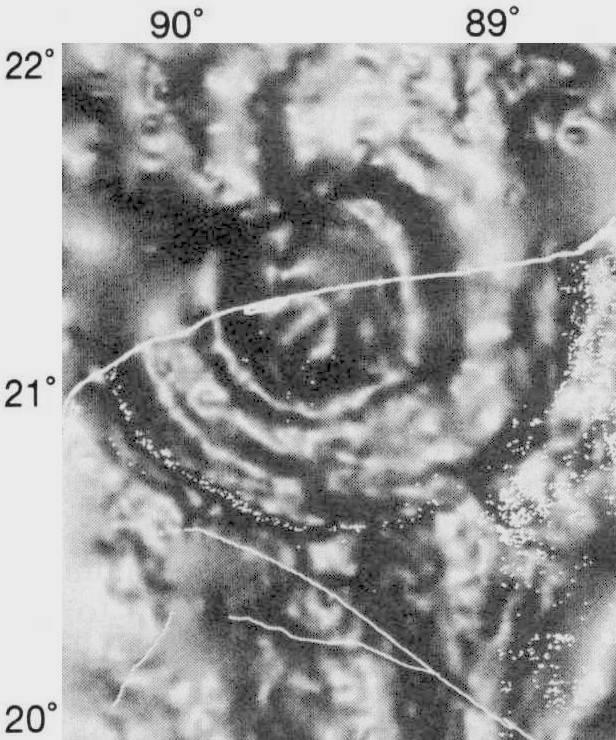

It's well accepted among scientists nowadays that the dinosaurs — along with three-quarters of all species on earth, land and sea — disappeared in the aftermath of the cataclysmic collision of a sizable asteroid or comet impacting the earth some 65 million years ago. Though the huge, multi-ringed, some 180 kilometers (112 miles) in diameter crater resulting from that cosmic trainwreck was found over a decade ago — buried at the northwestern tip of the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico, beneath up to a kilometer of sediments — it's apparently invisible as far as any visible effect on the surface topography of that part of the Yucatan (which basically is about as flat as a pancake) is concerned.

The deeply buried crater's seeming irrelevance to affairs on the surface is more apparent than real, however. The porous limestone (so-called “karst”) basement of the Yucatan is pierced by a plenitude of water-filled sinkholes, known locally as “cenotes”. These cenotes fall into patterns (easily visible on detailed road maps, for example) which, it turns out, congregate along the buried outer wall of the stupendous concentric-ringed prehistoric crater.

(Thus, one can swim in a pool lying atop the old dinosaur-killer crater rim. A fond remembrance: rather like the Pantheon in Rome, one might say, the underground cenote raised a vast dome vaulting through the rock ceiling into daylight for only a brief circle, through which sunlight poured to blaze in the otherwise dark, quiet pool, down the roof and along the sides of which stalactite and stalagmite columns marched….)

As A. R. Hildebrand and his colleagues (authors of the paper in Nature “Size and structure of the Chicxulub crater revealed by horizontal gravity gradients and cenotes” that is considered in this piece) describe it: 1

The cenote ring corresponds to (and was presumably created by) a zone of enhanced groundwater flow, as evidenced by a coincident low in the groundwater surface and the presence of freshwater springs where the cenote ring intersects the coast. High hydraulic conductivity is also indicated in the surrounding near-surface rocks by low hydraulic gradients and widespread response to tides. […] The ring consists mostly of water- and reed-filled cenotes of larger size (typically up to ~300 m [~1,000 feet] diameter) than the cenotes and dry karst pits found elsewhere on the peninsula. On the crater's east side, the size of the main ring's constituent cenotes allows it to be distinguished from the widespread karst features exterior to the crater. The main cenote ring is up to ~5 km [~3 miles] wide, and corresponds to a topographic low of up to ~5 m [~16 feet] over some of its length. Much of the permeability in karst terrains like the Yucatán peninsula is due to fracture systems, so it has been assumed that the cenote ring corresponds to a zone of enhanced fracturing. Although fractures are not directly observable along the cenote ring, we presume that a fracture system of ≤5 km width with orientations preferentially parallel to the underlying crater structure created the permeability that lead to the ring's formation. A zone of enhanced fracturing would also allow preferential erosion to create the topographic low associated with the ring.

The authors also note that, “The edges of the crater (and associated gravity-gradient features) correspond to bends in the coastline, and interior gradient features sometimes correlate with rocky points along the coastline.”

Beyond those surficial physical consequences of the subterranean crater's presence, the team assembling this marvelous figure and accompanying article, in effect — “merely” by careful measurement of seemingly trivial changes in gravity — have stripped the veil off this vast interred sepulchre, revealing the blasted hole in all its ruined glory! Kudos to the group for putting together this dramatic portrait — which isn't an image at all in the sense of a photograph, but might as well be for the clarity of the scene it presents.

The authors interpret the spectacular visage of the ancient crater: 1

Figure 1 reveals a striking circular structure centred near the Yucatán shoreline at ~89.57° N, 21.29° W. At least six concentric gradient features occur between ~10 and ~90 km [between ~6 and ~56 miles] radius. These features are probably most distinct in the southwest owing to denser sampling of the gravity field. Truncations of the gradient features often correspond to gaps in survey coverage. […] We interpret the outer four gradient maxima (at ~55 to ~90 km radii) to represent concentric faults in the crater's zone of slumping, as are also revealed by seismic reflection data. The inner two maxima probably represent the outer margins of the central uplift (at 20-25 km radius) and the peak ring and/or collapsed transient cavity (at 40-45 km radius). Radial gradients in the southwestern quadrant over the inferred ~40-km-diameter central uplift may represent structural ‘puckering’ as revealed at eroded terrestrial craters. Gradient features related to regional gravity highs and lows are visible outside the crater, but no concentric gradient features are apparent at radial distances >90 km [>56 miles]. Note that the crater's outer gradient and karst features are linear near the northern and tangential part of the Ticul fault […].

Hildebrand et al. acknowledge that, “the peripheral strong gradient features are truncated or diverted for the northern third of the crater.

Magnetic and seismic data confirm that a completely circular basin and impact structure is present, and some weak circular structure appears in the gravity data north of the truncation of the peripheral gradient features, but the cause of the truncation of Chicxulub's gravity expression remains to be understood.”

Here's the Abstract from A. R. Hildebrand and colleagues' Nature article: 1

It is now widely believed that a large impact occurred on the Earth at the end of the Cretaceous period, and that the buried Chicxulub structure in Yucatán, Mexico, is the resulting crater. Knowledge of the size and internal structure of the Chicxulub crater is necessary for quantifying the effects of the impact on the Cretaceous environment. Although much information bearing on the crater's structure is available, diameter estimates range from 170 to 300 km (refs 1-7), corresponding to an order of magnitude variation in impact energy. Here we show the diameter of the crater to be ~180 km [about 112 miles] by examining the horizontal gradient of the Bouguer gravity anomaly over the structure. This size is confirmed by the distribution of karst features in the Yucatan region (mainly water-filled sinkholes, known as cenotes). The coincidence of cenotes and peripheral gravity-gradient maxima suggests that cenote formation is closely related to the presence of slump faults near the crater rim.

1 A. R. Hildebrand, M. Pilkington, M. Connors, C. Ortiz-Aleman, and R. E. Chavez, “Size and structure of the Chicxulub crater revealed by horizontal gravity gradients and cenotes,” Nature, Vol. 376, Issue No. 6539 (dated 1995-08-03), pp. 415-417 [doi:10.1038/376415a0]. Requires pay-per-view for full text.

2

H. J. Melosh,

“Around and around we go,”

Nature,

Vol. 376, Issue No. 6539 (dated 1995-08-03), p. 387.

Accompanying news piece; requires pay-per-view for full text.

UPDATE: 2004-01-19 19:00 UT: Substantial rewording and material added from Hildebrand et al.

UPDATE: 2005-07-24 06:00 UT: Compression on crater image decreased.

Impearls: 2004-01-25 Archive

Earthdate 2004-01-16

The journal Science presented its annual “Breakthrough of the Year” special issue as usual in its final installment of the year. This last year's No. 1 Breakthrough, however, would appear to deserve honors beyond a single year's acclaim. It seems silly to talk about ”Breakthrough of the Century” this early in the 21st century, but the scientific results this last year in astrophysics are downright breathtaking.

Here's how Science's Charles Seife describes these illuminating advances: 1

A lonely satellite spinning slowly through the void has captured the very essence of the universe. In February, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) produced an image of the infant cosmos, of all of creation when it was less than 400,000 years old. The brightly colored picture marks a turning point in the field of cosmology: Along with a handful of other observations revealed this year, it ends a decades-long argument about the nature of the universe and confirms that our cosmos is much, much stranger than we ever imagined.

Five years ago, Science's cover sported the visage of Albert Einstein looking shocked by 1998's Breakthrough of the Year: the accelerating universe. Two teams of astronomers had seen the faint imprint of a ghostly force in the death rattles of dying stars. The apparent brightness of a certain type of supernova gave cosmologists a way to measure the expansion of the universe at different times in its history. The scientists were surprised to find that the universe was expanding ever faster, rather than decelerating, as general relativity — and common sense — had led astrophysicists to believe. This was the first sign of the mysterious “dark energy,” an unknown force that counteracts the effects of gravity and flings galaxies away from each other.

Although the supernova data were compelling, many cosmologists hesitated to embrace the bizarre idea of dark energy. Teams of astronomers across the world rushed to test the existence of this irresistible force in independent ways. That quest ended this year. No longer are scientists trying to confirm the existence of dark energy; now they are trying to find out what it's made of, and what it tells us about the birth and evolution of the universe.

Lingering doubts about the existence of dark energy and the composition of the universe dissolved when the WMAP satellite took the most detailed picture ever of the cosmic microwave background (CMB). The CMB is the most ancient light in the universe, the radiation that streamed from the newborn universe when it was still a glowing ball of plasma. This faint microwave glow surrounds us like a distant wall of fire. The writing on the wall — tiny fluctuations in the temperature (and other properties) of the ancient light — reveals what the universe is made of.

Long before there were stars and galaxies, the universe was made of a hot, glowing plasma that roiled under the competing influences of gravity and light. The big bang had set the entire cosmos ringing like a bell, and pressure waves rattled through the plasma, compressing and expanding and compressing clouds of matter. Hot spots in the background radiation are the images of compressed, dense plasma in the cooling universe, and cold spots are the signature of rarefied regions of gas.

Just as the tone of a bell depends on its shape and the material it's made of, so does the “sound” of the early universe — the relative abundances and sizes of the hot and cold spots in the microwave background — depend on the composition of the universe and its shape. WMAP is the instrument that finally allowed scientists to hear the celestial music and figure out what sort of instrument our cosmos is.

The answer was disturbing and comforting at the same time. The WMAP data confirmed the incredibly strange picture of the universe that other observations had been painting. The universe is only 4% ordinary matter, the stuff of stars and trees and people. Twenty-three percent is exotic matter: dark mass that astrophysicists believe is made up of an as-yet-undetected particle. And the remainder, 73%, is dark energy.

The tone of the cosmic bell also reveals the age of the cosmos and the rate at which it is expanding, and WMAP has nearly perfect pitch. A year ago, a cosmologist would likely have said that the universe is between 12 billion and 15 billion years old. Now the estimate is 13.7 billion years, plus or minus a few hundred thousand. Similar calculations based on WMAP data have also pinned down the rate of the universe's expansion — 71 kilometers per second per megaparsec, plus or minus a few hundredths — and the universe's “shape”: slate flat. All the arguments of the last few decades about the basic properties of the universe — its age, its expansion rate, its composition, its density — have been settled in one fell swoop.

As important as WMAP is, it is not this year's only contribution to cosmologists' understanding of the history of the universe. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) is mapping out a million galaxies. By analyzing the distribution of those galaxies, the way they clump and spread out, scientists can figure out the forces that cause that clumping and spreading — be they the gravitational attraction of dark matter or the antigravity push of dark energy. In October, the SDSS team revealed its analysis of the first quarter-million galaxies it had collected. It came to the same conclusion that the WMAP researchers had reached: The universe is dominated by dark energy.

This year scientists got their most direct view of dark energy in action. In July, physicists superimposed the galaxy-clustering data of SDSS on the microwave data of WMAP and proved — beyond a reasonable doubt — that dark energy must exist. The proof relies on a phenomenon known as the integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect. The remnant microwave radiation acted as a backlight, shining through the gravitational dimples caused by the galaxy clusters that the SDSS spotted. Scientists saw a gentle crushing — apparent as a slight shift toward shorter wavelengths — of the microwaves shining near those gravitational pits. In an uncurved universe such as our own, this can happen only if there is some antigravitational force — a dark energy — stretching out the fabric of spacetime and flattening the dimples that galaxy clusters sit in.

Some of the work of cosmology can now turn to understanding the forces that shaped the universe when it was a fraction of a millisecond old. After the universe burst forth from a cosmic singularity, the fabric of the newborn universe expanded faster than the speed of light. This was the era of inflation, and that burst of growth — and its abrupt end after less than 10-30 seconds — shaped our present-day universe.

For decades, inflation provided few testable hypotheses. Now the exquisite precision of the WMAP data is finally allowing scientists to test inflation directly. Each current version of inflation proposes a slightly different scenario about the precise nature of the inflating force, and each makes a concrete prediction about the CMB, the distribution of galaxies, and even the clustering of gas clouds in the later universe. Scientists are just beginning to winnow out a handful of theories and test some make-or-break hypotheses. And as the SDSS data set grows — yielding information on distant quasars and gas clouds as well as the distribution of galaxies — scientists will challenge inflation theories with more boldness.

The properties of dark energy are also now coming under scrutiny. WMAP, SDSS, and a new set of supernova observations released this year are beginning to give scientists a handle on the way dark energy reacts to being stretched or squished. Physicists have already had to discard some of their assumptions about dark energy. Now they have to consider a form of dark energy that might cause all the matter in the universe to die a violent and sudden death. If the dark energy is stronger than a critical value, then it will eventually tear apart galaxies, solar systems, planets, and even atoms themselves in a “big rip.” (Not to worry; cosmologists aren't losing sleep about the prospect.)

For the past 5 years, cosmologists have tested whether the baffling, counterintuitive model of a universe made of dark matter and blown apart by dark energy could be correct. This year, thanks to WMAP, the SDSS data, and new supernova observations, they know the answer is yes — and they're starting to ask new questions. It is, perhaps, a sign that scientists will finally begin to understand the beginning.

Note:

The publishers of Science, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), have made the

“Breakthrough of the Year”

The online article (linked to below) ends with numerous links to abstracts and full text of recent online research reports and review articles in this area.

(I like the title of the article from last year, by A. Gangui:

“A Preposterous Universe”!)

Interesting results, indeed.

1 Charles Seife, “Illuminating the Dark Universe,” Science, Vol. 302, Issue No. 5653 (dated 2003-12-19), pp. 2038-2039. Does not require subscription or pay-per-view; does require registration.

Impearls: 2004-01-25 Archive

Earthdate 2004-01-13

A recent issue (2003-10-30) of the journal Nature contains a pair of articles, a research report titled “Near-infrared flares from accreting gas around the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Centre” by R. Genzel (of the Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik) et al., and a news item by Harvard astronomer Ramesh Narayan on the same topic, called “Black holes: Sparks of interest.” 1, 2

I vividly remember reading decades ago one of the first books to come out on the quasars, those seemingly starlike (though stars impossibly brilliant to be seen at their distance) ‘quasi-stellar objects’ that were such a puzzle at the time. The book, as I recall, carefully considered the characteristics of the light spectrum emitted by quasars and came to the then-controversial conclusion (it seemed to me that the evidence, as the author presented it, practically screamed) that the terrific engines powering those gargantuan, universe-illuminating beacons were black holes — gigantic, what are now called supermassive, black holes. How can a black hole release energy, you may ask? As matter ‘infalls’ into a black hole, a portion of the matter's Einsteinian E = mc2 energy — i.e., nuclear energy — may be liberated, and the process can be far more efficient than what the stars, and we on Earth, use to produce nuclear power or explosions.

Nowadays the existence of black holes can scarcely be doubted, and any number have been located, from so-called ‘stellar-mass’ black holes incorporating a few times the sun's mass (relatively tiny in size, with a Schwarzschild ‘event horizon’ only a few kilometers across) to the ‘supermassive’ black holes, containing millions of times the mass of our sun, which drive the brilliant quasars as well as quieter, more lurking variants of these exotic beasts that occupy the centers of many of the galaxies.

New details about the light spectrum of one particular supermassive black hole — the closest to us, our own galaxy, the Milky Way's stupendous central black hole — promise to repeat this history of unfolding knowledge, by uncovering the precise modus operandi of this fabulous monster, the gigantic Hole at the heart of the Galaxy. The two Nature articles together describe detection of flares in the pattern of near-infrared light emission from the Galaxy's supermassive black hole, which has already provided illuminating details concerning it.

Harvard astronomer Ramesh Narayan describes the latest news, in his accompanying piece in Nature:

At the centre of the Milky Way is a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). As supermassive black holes go, Sgr A* is a relatively small one: it's four million times more massive than the Sun, but black holes up to 1,000 times more massive are known to exist in other galaxies. What makes Sgr A* special is that it is by far the closest supermassive black hole to Earth, making it a prime target for study. And, of course, it is our black hole, at the centre of our own Galaxy. Another, curious, feature is that Sgr A* is one of the dimmest black holes known.

Sgr A* has been studied extensively at long wavelengths, through the detection of radio- and millimetre-wavelength radiation from it; only recently has that information been complemented by images at shorter wavelengths, taken by the space-borne Chandra X-ray Observatory. On page 934 of this issue, Genzel and colleagues add more detail, with their detection of Sgr A* at infrared wavelengths, using the Very Large Telescope in Chile's Atacama Desert. Genzel et al., and another group led by Ghez, find that the brightness of Sgr A* at infrared wavelengths is highly variable, and flares frequently. These observations, reflecting similar patterns seen earlier in X-rays, open a new window on this enigmatic source.

Some supermassive black holes in distant galaxies are observed as very bright quasi-stellar objects, or quasars, that often outshine an entire galaxy of stars. Those black holes accrete (absorb) a lot of gas from their surroundings and in so doing convert a good fraction, say 10%, of the mass energy of that gas to radiation. Their luminosities are nearly equal to the maximum allowed — the so-called Eddington limit, which is proportional to the mass of the object. Sgr A*, in contrast, is extremely dim, radiating at only a billionth of the Eddington limit for its mass. In this respect it resembles the vast majority of black holes in the Universe, which are mostly very dim.

Why is Sgr A* so dim? It is true that it has less gas to accrete, compared with the bright black holes in quasars — but this is only around 10,000 times less, not a billion times. Two other factors are believed to contribute to its dimness. First, in contrast to the accretion flows in quasars, the gas flow in Sgr A* is radiatively inefficient: only a very small fraction of its mass energy is converted to radiation. Second, as a direct consequence of this radiative inefficiency, only a small fraction of the available gas actually accretes onto the black hole, the rest being ejected from the system.

This still leaves the fundamental question of exactly how an accretion flow converts mass energy to radiation and why the process is very efficient in bright quasars but highly inefficient in Sgr A*. Something is clearly different about the physics in bright black holes and in dim ones. Unfortunately, the relevant effects are complex and poorly understood, and it has become clear in recent years that real progress will be achieved only when we have more detailed observational clues. The infrared detections of Sgr A* by Genzel et al., coupled with Chandra's X-ray observations, may be the breakthrough we have been looking for.

The fact that the emission from Sgr A* varies over tens of minutes, and is almost periodic, indicates that the radiation comes from gas orbiting close to the black hole. This is not unexpected. What is surprising is that Sgr A* emits frequent massive flares of radiation at both infrared and X-ray wavelengths, suggesting that the conversion of mass to radiation is not steady and continuous, but very erratic. There are several possible explanations. One is that the radiatively inefficient accretion flow ejects gas in spurts rather than continuously, and that each ejection of a blob of gas is accompanied by a spurt of radiation. Another is that the amount of gas accreting onto the black hole itself fluctuates, causing the emission to vary. A third idea, perhaps the simplest, is that the accretion engine shorts out once in a while. Lines of magnetic field pervade the accretion disk, and occasionally these may become so distorted that they ‘snap’ and new lines form. These magnetic reconnection events would produce streams of energetic particles and sparks of radiation (Fig. 1).

It is not clear at present which, if any, of these ideas is correct, or how the radiation processes actually work in detail. But the beauty of having a flaring source such as Sgr A* is that each flare provides a new and independent view of the underlying physical processes. So by collecting and studying data on many flares, we may learn much more than from a steady source.

After chewing on that ‘supermassive’ entree, try this meaty excerpt from Genzel et al.'s research report:

The flares' location close to the central black hole, as well as the temporal substructure, poses a serious challenge to models in which the flares originate from rapid shock cooling of a large-scale jet, or are due to passages of stars through a central accretion disk.

The few-minute rise and decay times, as well as the quasi-periodicity, strongly suggest that the infrared flares originate in the innermost accretion zone, on a scale less than ten Schwarzschild radii (the light travel time across the Schwarzschild radius of a 3.6-million-solar-mass black hole (1.06 × 1012 cm) is 35 s). If the substructure is a fundamental property of the flow, the most likely interpretation of the periodicity is the relativistic modulation of the emission of gas orbiting in a prograde disk just outside the last stable orbit (LSO). If the 17-min period can be identified with this fundamental orbital frequency, the inevitable conclusion is that the Galactic Centre black hole must have significant spin. The LSO frequency of a 3.6-million-solar-mass, non-rotating (Schwarzschild) black hole is 27 min. Because the prograde LSO is closer in for a rotating (Kerr) black hole, the observed period can be matched if the spin parameter is J/(GMBH/c) = 0.52 (± 0.1, ± 0.08, ± 0.08, where J is the angular momentum of the black hole); this is half the maximum value for a Kerr black hole. (The error estimates here reflect the uncertainties in the period, black-hole mass (MBH) and distance to the Galactic Centre, respectively; G is the gravitational constant.) For that spin parameter, the last stable orbit is at a radius of 2.2 × 1012 cm. Recent numerical simulations of Kerr accretion disks indicate that the in-spiralling gas radiates most efficiently just outside the innermost stable orbit. Our estimate of the spin parameter is thus a lower bound.

Other possible periodicities, such as acoustic waves in a thin disk, Lense-Thirring or orbital node precession are too slow for explaining the observed frequencies for any spin parameter. (The 28-min timescale of the quiescent emission corresponds to a radius of 3.2 × 1012 cm for a prograde orbit of J/(GMBH/c) = 0.52; the last stable retrograde orbit for that spin parameter has a period of 38 min at a radius of 4 × 1012 cm). Lense-Thirring precession and viscous (magnetic) torques will gradually force the accreting gas into the black hole's equatorial plane. Recent numerical simulations indicate that a (prograde) disk analysis is appropriate to first order even for the hot accretion flow at the Galactic Centre.

To extract some fascinating details from this piece, the Schwarzschild radius (radius of the event horizon) of the 3.6 million solar mass ‘Galactic Centre’ (as they call it) black hole is 35 light seconds, or some 10.6 million kilometers (about 6.6 million miles); this is about 15¼ times the size of the sun (695,000 km radius), and (at 0.07 Astronomical Unit) about one-sixth the radius of the orbit of Mercury (0.4 AU) in our solar system. As the authors conclude, “the most likely interpretation of the periodicity” in the observed flaring in the infrared emission of the black hole — including a 17-minute periodicity — is “the relativistic modulation of the emission of gas orbiting in a prograde disk just outside the last stable orbit (LSO).” ‘Prograde’ means orbiting in the direction of spin of the black hole. The period of the ‘last stable orbit’ of a non-rotating black hole of this mass is 27 minutes; thus a 17-minute orbital periodicity could not exist if the black hole were not rotating.

For a rotating black hole, Genzel et al.'s article points out, “the observed period can be matched if the spin parameter” is about 0.52 (52%) of the maximum spin such a black hole could possibly possess. “For that spin parameter, the last stable orbit is at a radius of 2.2 × 1012 cm” from the ‘center’ of the black hole — which is 22 million km (13 million miles), or some 31 times the size of the sun, and (at about 0.15 AU) more than one-third the radius of Mercury's orbit. Something in this ‘prograde last stable orbit’ would orbit some 11 million km (7 million miles) above the ‘Galactic Central’ (as we'll call it) black hole's event horizon. If I understand the physics correctly, something like a spaceship could venture below the ‘last stable orbit,’ but an unpowered trajectory would inevitably spiral into the event horizon, from whence no return is possible; a spaceship would have to expend power (if it had enough) to return from below the ‘last stable orbit.’

As Genzel and his colleagues wrote, “Recent numerical simulations of Kerr accretion disks indicate that the in-spiralling gas radiates most efficiently just outside the innermost stable orbit. Our estimate of the spin parameter is thus a lower bound.” The piece also notes that “The 28-min timescale of the quiescent emission corresponds to a radius of 3.2 × 1012 cm.” This ‘quiescent emission’ gas is thus orbiting at a radius of 32 million km (about 20 million miles), which is some 0.21 AU or a little over half the size of Mercury's orbit. The article additionally points out that the last stable retrograde orbit for that Galactic Central black hole spin parameter (0.52) “has a period of 38 min, at a radius of 4 × 1012 cm,” or 40 million km (about 25 million miles), which is some 57 times the size of the sun, and (at about 0.26 AU) approximately two-thirds the radius of Mercury's orbit.

Even though the last stable orbit, in any direction, around the ‘Galactic Central’ black hole lies below the height of Mercury's orbit in our solar system, if a planet such as Mercury were to swing by at a similar distance from the ‘center’ of Galactic Central, it would have to possess a far greater velocity to successfully orbit, due to the enormously greater mass and thus gravitational strength of the central attractor in that system, or else it would simply plop into the black hole. Notice the difference in orbital period: 38 minutes for the (retrograde) last stable orbit (which would orbit Galactic Central at two-thirds the distance of Mercury) versus Mercury's period of 88 days to circle our sun.

Disregarding complications such as tidal forces which tend to pluck apart a too-closely-orbiting planet, and presuming an appropriately large enough orbital velocity, an object or planet would be able to stably orbit the ‘Galactic Central’ black hole — at or beyond the so-called ‘last stable orbit’ for the direction in which it is orbiting.

How fast would that orbital velocity have to be?

Taking the prograde direction, and ignoring relativistic effects, the circumference (2πr) of a 22 million km radius circular orbit is about 138 million km.

This distance must be traversed during each 17 minute orbital period, requiring a speed of some 136,000 km/second (84,000 miles/second), or approximately 45% of the speed of light!

1 R. Genzel, R. Schödel, T. Ott, A. Eckart, T. Alexander, F. Lacombe, D. Rouan, and B. Aschenbach, “Near-infrared flares from accreting gas around the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Centre,” Nature, Vol. 425, Issue No. 6961 (date 2003-10-30), pp. 934-937 [doi:10.1038/nature02065]. Requires subscription or pay-per-view.

2 Ramesh Narayan, “Black holes: Sparks of interest,” Nature, Vol. 425, Issue No. 6961 (date 2003-10-30), pp. 908-909 [doi:10.1038/425908a]. Requires subscription or pay-per-view.

Impearls: 2004-01-25 Archive

Earthdate 2004-01-05

Stephen Bainbridge at Professor Bainbridge.com responded to Impearls' earlier piece on the Sarmatians (permalink) with a rebuttal, “Were the Rohirrim Sarmatians? No.”

I'm a bit bemused by Prof. Bainbridge's reply, because as Impearls' earlier article tried to make clear, it was Peter Jackson's version of The Lord of the Rings (and the filmmakers' declared grafting together of the memorable Vikings from history with their need for a horse-oriented culture to populate the land of Rohan) to which it was responding. (It's way too many years ago that I read Tolkien for me to feel comfortable replying thus to the original books.) Bainbridge, on the contrary, explicitly talks about Tolkien's version of Middle Earth, from which obviously the Jacksonian films have somewhat diverged. This makes the comparison a bit apples and oranges.

Impearls will rise to the occasion nonetheless! See below for various parts of the discussion, including consideration of candidate peoples.

The important point is that seeking to find an exact match between any ancient people and the folk of what is after all (I know I'll get lynched for this) a work of fantasy and fiction, is (you'll pardon me, I hope, Stephen) a fool's errand! Nonetheless, without being so dogmatic, there's much in this area that's interesting (to say the least), educational, and fun! Let's investigate the possibilities, after setting our goals and requirements.

As the earlier article tried to convey, what is being sought is a folk like or reminiscent of the Rohirrim, not some will-o'-the-wisp of who exactly, really was the Rohirrim (answer: nobody, really). No, the real goal, here at Impearls anyway, is to illuminate a few little known (though fascinating and significant) peoples in history through the vivid example of the Rohirrim — whom they resemble — and vice versa: to cast a light on the Rohirrim through the spectacle of real peoples in history!

Keeping that in mind, let's consider Bainbridge's stated requirements:

- Language: Old English

- Place of origin: Somewhere to the north of present location

- Current location: Occupying lands that had once been part of the domain of a neighboring culture that is both older and more highly developed

- War panoply includes: Mainly cavalry, saddles with stirrups, spears, swords (probably iron), and bows (long bows in the movie, although composite bows seem a more likely candidate for a cavalry army)

- Lifestyle: Possibly semi-nomadic herding, but with a permanent residence for the king

- Fortifications: A place of refuge (i.e., Helm's Deep; which in John Keegan's technical terminology seems to be a hybrid between a refuge and stronghold)

Now edit these requirements, according to the above criteria. The first of these, language, deserves a section of its very own.

Among Bainbridge's requirements, the rest we'll consider in a moment, Stephen declares that the Rohirrim spoke Old English (!), pointing to a note by Tolkien which, Stephen asserts, verifies this point of view. Now, we'll look at Tolkien's note shortly, but all one really has to do is glance at a map of Middle Earth to discern that it's nowhere near to possibly representing Britain, or Germany, or Europe, or anywhere else on (non-Middle) Earth; and thus nowhere where true speakers of Old English have ever lived in any numbers (that is, Britain or — stretching things a bit — the lower Elbe valley/Jutland peninsula region of Germany). Ergo, the people of Middle Earth cannot “really” (love this sort of thing when talking about fiction!) have spoken Old English.

The notes that Bainbridge points to in Tolkien's Lord of the Rings books further contradict the point he's trying to make. Tolkien makes it quite clear in these notes that in his “translation,” as he puts it, he's mapping the archaic variants of his so-called “Westron Common Speech” such as the Rohirrim, men of Gondor, and some others in Middle Earth spoke, into what he calls “ancient English.” As Tolken says: 1

In presenting the matter of the Red Book, as a history for people of today to read, the whole of the linguistic setting has been translated as far as possible into terms of our own times. Only the languages alien to the Commmon Speech have been left in their original form; but these appear mainly in the names of persons and places.

The Common Speech, as the language of the Hobbits and their narratives, has inevitably been turned into modern English. […] The language of Rohan I have accordingly made to resemble ancient English, since it was related both (more distantly) to the Common Speech, and (very closely) to the former tongue of the northern Hobbits, and was in comparison with the Westron archaic.

From this and context of intervening pages, it's clear that the “actual” (!) Rohirrim and other languages of Middle Earth were nothing like Old English or any other real or historic Earth language except by analogy.

It also must be propounded that the language a candidate people from history once spoke is nearly wholly orthogonal to the important issues of whether and how that folk resembles the Rohirrim. Accordingly, language will not be regarded as a determining factor.

Stirrups might also be briefly discussed. Bainbridge argues that the Sarmatians just can't be the Rohirrim because Impearls' article claims the Sarmatians didn't have stirrups — whereas, as Stephen points out, stirrups are mentioned in the books as used by the Rohirrim.

Bainbridge then goes on to dispute, however, whether Sarmatians really did lack the stirrup, providing a link to an opposing point of view. It's true, there are scholars who maintain that the Sarmatians had the stirrup. (I've heard they're mostly Hungarian, and therefore perhaps suspect of being biased in this regard; possibly I'm libeling them, and I admit I don't know.) There are even authorities who argue that the Scythians — the Sarmatians' half-millennial predecessors on the European steppe — had the stirrup. Fundamentally, however, the main reason, I think (as there seems to be no archeological proof), for concluding that the stirrup wasn't introduced until very late antiquity/early medieval times is it's hard to believe perceptive military observers like Romans and others wouldn't have picked up the trick from Goths/Sarmatians/Scythians if they'd had the concrete example staring them in the face earlier. The Romans in particular had Sarmatian auxiliaries serving in the Roman army; if the Sarmatians possessed stirrups during this period, it's difficult to understand why Romans wouldn't then have started using them too. (Moreover, I think Stephen's disputing whether Sarmatians lacked the stirrup detracts from his argument quite a bit! But it reveals Bainbridge as an honest debater.)

Beyond that specific point, however, it appears (as with language above) that the presence or absence of a single item of gear such as stirrups ought not to be an overriding factor in evaluating whether and how closely a given folk resembles the Rohirrim. Accordingly, stirrups will not be considered a determining characteristic.

Continuing the reevaluation of Bainbridge's requirements:

- Language: disposed of above as a requirement.

- Place of origin: While a northerly origin can be kept in mind as what might be called a nice to have, “reminiscence” attribute for a people, this aspect is pretty much irrelevant to the question of, are they like the Rohirrim? Remember: what's being sought are interesting folk that resemble the Rohirrim, not peoples some accidental element of whose history aligns with the fictional history of Middle Earth.

- Current location — i.e., “occupying lands that had once been part of the domain of a neighboring culture that is both older and more highly developed,” as Bainbridge put it. This aspect is also possibly worthy of consideration, though once again largely disconnected from the personality, characteristics and accoutrements that a “horsey” culture like the Rohirrim actually possessed. Let's keep it in mind, however.

- War panoply: Bainbridge's itemization is pretty good here, except perhaps for the necessity (as he sees it) to have stirrups, and another consideration that he doesn't see. Stirrups shouldn't be a deciding factor in meeting the overall goal, but another arms requirement needs to be added: armor. Cavalry and foot soldiers ought to wear at least some armor (as the Rohirrim weren't light cavalry), most probably helmet, chain mail, and shield, which the Rohirrim troops in the LOTR films prominently displayed. Shields need not be round, nor is it very important if a particular “horsey” culture's cavalry used, say, bows rather than spears. Contrary to Stephen's preference, there's no problem if some arms and armor are made of bronze rather than iron.

- Lifestyle: As Bainbridge says, either nomadic or agricultural lifestyles are fine, but there should be some permanent residences, as the Rohirrim so obviously possessed in the films. As Impearls' earlier piece pointed out, nomad empires in history “covered the most medley conglomerations of nomads and peasants,” so there normally were settled peoples and some agriculture performed within such states. See below (e.g., under Scythians and Avars) for examples of the fortresses and permanent residences that these so-called “nomads” maintained.

- Fortifications, or place of refuge: Yes, there should be such, but see the previous item above.

- A final consideration might be added to the list: allowing women to fight! That would seem to be one of the expected characteristics for the Rohirrim, given the screen version of the LOTR at least. It is, however, a “gotcha” requirement: Given history as it has unfolded, few (no?) real cultures would be able to meet this requirement were it to be rigidly applied — except for the Sarmatians!

Given the foregoing list of considerations and requirements, who are some of the peoples in history who could serve, hauntingly, reminiscently, as models for the Rohirrim, and vice versa? Here's a list of (major) candidate horse cultures (no doubt there are others — in China, India, Africa, elsewhere — that I know too little of to include), listed roughly in chronological order:

- Cimmerians

- Scythians

- Parthians

- Sarmatians

- Goths

- Avars

- Khazars

- Bulgars

- Magyars

- Normans

- Viking/Nomad/Serf combinations of various sorts

“Light” (relatively or entirely unarmored) horse warriors such as the Huns, Arabs, Seljuk Turks, and Mongols have been omitted from the list, as insufficiently like the Rohirrim — i.e., the Rohirrim wore helmets and mail armor and were certainly not light cavalry. We'll not consider all of these peoples today, but review the eldest of them, and leave the remainder (italicized above) for another day.

The Cimmerians were the first known nomad horse warriors in history, residing by about 1200 BC on the grassy steppe north of the Caucasus, Black Sea, and in central Europe. Indo-European speakers and with an Iranian ruling class, the Cimmerians assaulted several kingdoms in the Caucasus and Asia Minor towards the end of the 8th and during the 7th centuries BC, seemingly as a consequence of being ousted from their homes by the invading Scythians, who subsequently replaced them as masters of the steppe.

Historian William H. McNeill describes the situation, writing in Encyclopædia Britannica: 2

The first sign that steppe nomads had learned to fight well from horseback was a great raid into Asia Minor launched from the Ukraine about 690 BC by a people whom the Greeks called Cimmerians. Some, though perhaps not all, of the raiders were mounted. Not long thereafter, tribes speaking an Iranian language, whom the Greeks called Scythians, conquered the Cimmerians and in turn became lords of the Ukraine.

After invading Lydia and subsequently being expelled from that country, the Cimmerian refugees apparently settled in Cappadocia (whose name in Armenian is “Gamir”), and also survived on the Hungarian plain until about 500 BC.

The Scythians, as previously noted, displaced the Cimmerians from the European steppe during the 8th and 7th centuries BC, and over the next half millennium dominated the northern borderlands of Persia, Asia Minor, and Greece. Eneyclopædia Britannica's article “Scythian” describes them: 3

The Scythians were feared and admired for their prowess in war and, in particular, for their horsemanship. They were among the earliest people to master the art of riding, and their mobility astonished their neighbours. The migration of the Scythians from Asia eventually brought them into the territory of the Cimmerians, who had traditionally controlled the Caucasus and the plains north of the Black Sea. In a war that lasted 30 years, the Scythians destroyed the Cimmerians and set themselves up as rulers of an empire stretching from west Persia through Syria and Judaea to the borders of Egypt. The Medes, who ruled Persia, attacked them and drove them out of Anatolia, leaving them finally in control of lands which stretched from the Persian border north through the Kuban and into southern Russia.

The Scythians were remarkable not only for their fighting ability but also for the civilization they produced. They developed a class of wealthy aristocrats who left elaborate graves filled with richly worked articles of gold and other precious materials. This class of chieftains, the Royal Scyths, finally established themselves as rulers of the southern Russian and Crimean territories. It is there that the richest and most numerous relics of Scythian civilization have been found. Their power was sufficient to repel an invasion by the Persian king Darius I in about 513 BC.

Historian William H. McNeill indicates the Scythians' impact on the history of world civilization: 4

[T]he Scythians had erected a loose confederacy that spanned all of the Western Steppe. The high king of the tribe heading this confederacy presumably had only limited control over the far reaches of the Western Steppe. But on special occasions the Scythians could assemble large numbers of horsemen for long-distance raids, such as the one that helped to bring the Assyrian Empire to an end. After sacking the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in 612 BC, the booty-laden Scyths returned to the Ukrainian steppe, leaving Medes, Babylonians, and Egyptians to dispute the Assyrian heritage. But the threat of renewed raids from the north remained and constituted a standing problem for rulers of the Middle East thereafter.

Despite an impression one might get that these great nomad confederacies/empires lacked settlements of any kind, fortified and otherwise, historian Gavin R.G. Hambly points out the contrary, writing in the article “Central Asia” in Encyclopædia Britannica: 5

From the second half of the 8th century BC, the Cimmerians were replaced by the Scythians, who used iron implements. The Scythians created the first known typical Central Asian empire. […] [T]he Greek historian Herodotus […] provided the first and perhaps the most penetrating description of a great nomad empire. In more than one respect the Scythians appear as the historical prototype of the mounted warrior of the steppe; yet in their case, as in others, it would be mistaken to see in them aimlessly roaming tribes. The Scythians, like most nomad empires, had permanent settlements of various sizes, representing various degrees of civilization. The vast fortified settlement of Kamenka on the Dnieper River, settled since the end of the 5th century BC, became the centre of the Scythian kingdom ruled by Ateas, who lost his life in a battle against Philip II of Macedon in 339 BC.

What kind of soldier and army did the Scythians field? Britannica's article “Scythian” describes them:

The Scythian army was made up of freemen who received no wage other than food and clothing, but who could share in booty on presentation of the head of a slain enemy. Many warriors wore Greek-style bronze helmets and chain-mail jerkins. Their principal weapon was a double-curved bow and trefoil-shaped arrows; their swords were of the Persian type. Every Scythian had at least one personal mount, but the wealthy owned large herds of horses, chiefly Mongolian ponies. Burial customs were elaborate and called for the sacrifice of members of the dead man's household, including wife, servants, and a number of horses.

Assessment: We see that the Scythians possessed large fortified settlements (as did many another horse-nomad empire), and in personal arms resembled the mailed horse warriors of the Rohirrim.

The Scythian folk known as the Parni during the 4th century BC was one of three tribes in the Dahae confederacy living east of the Caspian Sea. Following the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC), the tribe moved south into the area of what is now northeastern Iran. There they adopted the speech and lifestyle of the settled inhabitants, and around the middle of the 3rd century began a struggle against Alexander's successor state in Asia, the Seleucid Empire.

About 238 BC the Parthians defeated and killed the independent-minded governor of the area, detaching the province from the Seleucid state. Based on its own resources, Parthia had been one of the poorer regions of the Seleucid realm, but it happened to incorporate a considerable stretch of the rich “Silk Road” caravan route, and lucrative tolls from the caravans passing through allowed the new kingdom to prosper.

The ruling Arsacid dynasty encouraged the idea that the Parthian domain was the inheritor of the earlier Achaemenid Persian Empire (that we in the West remember through its contests with the classical Greeks). This sentiment was not shared by the Persians themselves (inhabitants of the region of Persis in southern Iran), however, who regarded the Parthians as foreigners and barbarians, and fought alongside the Seleucids and against the Parthians. (Ultimately, half a millennium later, the Persians would take back “their” empire, when around 224 AD the Parthians were overthrown and the Sasanian Empire installed.)

During the 2nd century BC the Parthians progressively annexed almost all the Seleucid dominion except a remnant of Syria west of the Euphrates (which ultimately went to Rome), producing a realm about equal to modern Iran and Iraq put together. In the four and a half centuries it endured, Parthia remained a largely decentralized and feudal domain (the Seleucid state had also been quite decentralized with large amounts of local self-government). Despite hearkening back to the days of the Achaemenids, the Parthians' ruling Arsacids did not despise (until after about the turn of the millennium anyway) the Greek Hellenistic heritage inherited from Alexander. Whole prosperous Greek cities, autonomous in their governance — such as Seleucia on the Tigris, right across the river from the Parthian capital at Ctesiphon (forming, in fact, a kind of dual capital spanning the Tigris) — flourished within the Parthian domain, while Greek remained one of the official languages of the empire. An illuminating glimpse of the Parthians' “phil-Hellenism” may be seen in the story from the Greek writer Plutarch that the excised head of invading Roman general Crassus was brought before the Parthian king while he was entertaining a performance of Euripides' play The Bacchae. 6

Assessment: So how do the Parthians stack up compared with the Rohirrim? The Parthians used heavy cavalry — their armor was probably heavier than the Rohirrim's, in fact, though I don't have exact details on this. They certainly occupied territory once “part of the domain of a neighboring culture that is both older and more highly developed.” Place of origin was to the north: check. They had extensive fortifications and permanent settlements. Yes, the Parthians clearly rank highly as possible Rohirrim.

The Sarmatians were featured in Impearls' earlier article Horsey Vikings I (permalink). Why emphasize them in particular?

- They're an interesting folk, little known to most people today.

- Sarmatians occupied an important borderland of the Roman Empire during most of its history, and participated in major historic events involving that Empire.

- Sarmatians are the conduit which led to the medieval knight: that's a big one. As Impearls' earlier piece pointed out, Norman knights shown in the Bayeux Tapestry are equipped strikingly similarly to the Sarmatians' warrior kit — which makes sense since that's from whence it was derived! Notice that the Rohirrim cavalry displayed in Jackson's Lord of the Rings films are also nearly exact replicas of the Norman knights of Bayeau Tapestry — except that the Rohirrim used a round shield, just like the Sarmatians!

- It may even be that Sarmatians were the inspiration for King Arthur's knights. It is known that Sarmatian auxiliaries serving as part of the Roman army — equipped, as Sarmatians were, as armored horse warriors — were stationed in Roman Britain. It has been suggested that, to the extent that legends of King Arthur's knights correspond to reality, these Sarmatian warriors may have inspired (and perhaps served as the nucleus for) a troop of armored knights during the post-Roman period in Britain when Arthur is supposed to have lived.

- While talking about exact matches, what other people in history has ever allowed their womenfolk to fight as warriors! (I'm tempted to say Q.E.D. to the Bainbridge debate in this regard, but I shan't be so cruel!)

Assessment: The Sarmatians are no precise match for Rohan's Rohirrim — but then no one else is (or can be) either. They do come about as close as anyone can to that ideal, especially given the last item above.

The Goths occupy a unique place in this story, the only native agriculturists (except, arguably, the Parthians, after they adopted a settled lifestyle) among hordes of nomads. During the Gothic dominance of the east European plain (2nd through 4th centuries AD), that was the only moment in post-Cimmerian history up to the modern era when the steppe was not in thrall to nomadic empires. The Goths also spoke a Germanic tongue, which is significant for those who think language is an important criterion in this regard.

The Goths — or at least a ruling elite — originated according to Gothic legend in what is now Sweden. Certain place names, such as the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea, appear to recall the Gothic presence. Encyclopædia Britannica describes those days: 7

According to their own legend, reported by the mid-6th-century Gothic historian Jordanes, the Goths originated in southern Scandinavia and crossed in three ships under their king Berig to the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, where they settled after defeating the Vandals and other Germanic peoples in that area. Tacitus states that the Goths at this time were distinguished by their round shields, their short swords, and their obedience toward their kings. Jordanes goes on to report that they migrated southward from the Vistula region under Filimer, the fifth king after Berig and, after various adventures, arrived at the Black Sea.

This movement took place in the second half of the 2nd century AD, and it may have been pressure from the Goths that drove other Germanic peoples to exert heavy pressure on the Danubian frontier of the Roman Empire during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Throughout the 3rd century Gothic raids on the Roman provinces in Asia Minor and the Balkan peninsula were numerous, and in the reign of Aurelian (270-275) they obliged the Romans to evacuate the trans-Danubian province of Dacia. Those Goths living between the Danube and the Dniester rivers became known as Visigoths, and those in what is now the Ukraine as Ostrogoths.

Historian William H. McNeill points out that Goths in their new home in what is now the Ukraine “swiftly adopted the habits and accoutrements of steppe nomads.” 8 Goths thus became the only mounted warriors among Germans for centuries to come — which Rome learned to her sorrow.

Continuing with the story of the Ostrogothic kingdom in the Ukraine, Britannica notes that: 9

Invading southward from the Baltic Sea, the Ostrogoths built up a huge empire stretching from the Don to the Dniester rivers (in present-day Ukraine) and from the Black Sea to the Pripet Marshes (southern Belarus). The kingdom reached its highest point under King Ermanaric, who is said to have committed suicide at an advanced age when the Huns attacked his people and subjugated them about 370. Although many Ostrogothic graves have been excavated south and southeast of Kiev, little is known about the empire. The Ostrogoths were probably literate in the 3rd century, and their trade with the Romans was highly developed.

During the late 4th century the fierce Huns struck from the east, and after a period of successful defense, both Visi- and Ostrogoths were overwhelmed and obliged to accept either Hunish dominance, or escape to the west and south. Groups of both Visigoths and Ostrogoths eventually made their way into the Roman Empire — more or less with Roman permission — and had various adventures therein.

Visigoths. In 378 AD the Visigothic cavalry overwhelmed the Roman army near Adrianople, inflicting one of the worst defeats in Roman history. Under Alaric, in 410 they sacked the city of Rome. In 418 the Visigoths accepted Roman “federate” status and were settled as nominal allies in the Aquitaine region of southern Gaul, and though they remained officially bound to Rome for many years, over the rest of the century from this nucleus they built a mighty kingdom incorporating much of what is now France and most of modern Spain and Portugal.

As a result of the battle of Vouillé (507), the Visigoths were expelled from Gaul (except for the small Mediterranean coastal strip of Septimania) by the Franks under Clovis. Excepting Septimania, the Visigoths withdrew behind the Pyrenees mountains into their Spanish dominions, and remained there, their kingdom slowly percolating along, not very prosperously, until they were overwhelmed by the Arab Muslim irruption across the strait at Gibraltar in 711. The Goths of Septimania, at first passing with the rest of the Visigothic realm to the Muslims of Spain, eventually transferred their allegiance to the Franks, and the region was afterward known for centuries in France as “Gothia.”

From refuges in the northern mountains of Spain, under frequent attack from the Muslim Caliphate centered in Cordova to the south, over more than a half millennium of time the Visigothic kingdom's heirs slowly returned, in the Spanish-Portuguese Reconquista (see Impearls' article Crusades I [permalink]).

Ostrogoths. The Ostrogothic story was different. The Ostrogoths, after first being settled by the East Roman Empire in what used to be called Yugoslavia, towards the end of the 5th century were induced by the East Roman Emperor to invade Italy, ruled by the barbarian king Odoacer, who had lately put an end to the remains of the Roman Empire in the West. The Ostrogoths, under their king Theodoric the Great, defeated Odoacer, and in 493 Theodoric became king of the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy. For most of the next half century Ostrogothic Italy remained relatively prosperous and enlightened amid the darkness taking hold elsewhere. Roman civilization had not yet winked out in Italy; literary works continued to be written in Latin, and Theodoric maintained a benevolent rule over both Italians and Ostrogoths.

This state of affairs, after the death of Theodoric, was brought to an end by the Eastern Emperor Justinian, who in 535 launched an invasion of Ostrogothic Italy in order to retrieve it for the Roman Empire, commanded by the brilliant general Belisarius, who had just lately reconquered Vandal Africa for the Byzantine domain. Justinian, however, was paranoid and suspicious of Belisarius, and failed to provide him with enough troops, whereupon the war dragged on literally for decades, devastating most of Italy and doing much to propel it into the Dark Ages. Belisarius was recalled, his successors proved incompetent; Belisarius was sent back, but still not given adequate backing; finally, another general, the eunuch Narses, was installed in command, with a massive army properly supported this time, and the war, finally in 554, was won. Devastated Italy — Rome itself — were indeed recovered for the Roman Empire; that is, until the far more barbaric Lombards invaded a few years later, completing the demolition job on classical Italy. The Ostrogoths of Italy were not heard of again.

Gothic continued to be spoken for centuries, however, by peasants in the Danube valley, while a small enclave of Ostrogoths, separated from the main movements of their people, retained its identity in the Crimea (modern Ukraine) throughout the medieval period.

Assessment: The Goths, Ostro- and Visi-, one would have to say, are among the strongest candidates for a close resemblance to the Rohirrim. Agriculturalists, and Germanic speakers, these are additional factors in their favor for those who value such things. After picking up numerous nomads, Sarmatians among them, into their confederacy, they became fine horse warriors, dominating the east European steppe for a couple of hundred years. Furthermore, the Goths came from “the north,” and after conquering Roman Dacia (modern Romania), they certainly occupied “lands that had once been part of the domain of a neighboring culture that is both older and more highly developed.” Ater occupying much of formerly-Roman Gaul, Spain, and Italy, this was even more true. Goths, one must conclude, are fine candidate folk to be the Rohirrim.

The Avars were a nomadic folk, as Encyclopædia Britannica notes, “of undetermined origin and language,” who in the 6th century AD built a vast empire in central Europe stretching from the Adriatic Sea to the Baltic, and from the Elbe River to the Dnieper. Avars made their entrance onto the stage of history when, according to Britannica: 10

Inhabiting an area in the Caucasus region in 558, they intervened in Germanic tribal wars, allied with the Lombards to overthrow the Gepidae (allies of Byzantium), and between 550 and 575 established themselves in the Hungarian plain between the Danube and Tisza rivers. This area became the centre of their empire, which reached its peak at the end of the 6th century.

This movement of the Avars which ended up in the central European plain was originally instigated, however, by Byzantine diplomacy, as historians John L. Teall and Donald MacGillivray Nicol, in their article “The History of the Byzantine Empire” in Britannica, point out: 11

As long as the financial resources remained adequate, diplomacy proved the most satisfactory weapon in an age when military manpower was a scarce and precious commodity. Justinian's subordinates were to perfect it in their relationships with Balkan and south Russian peoples. For, if the Central Asian lands constituted a great reservoir of people, whence a new menace constantly emerged, the very proliferation of enemies meant that one might be used against another through skillful combination of bribery, treaty, and perfidy. East Roman relations in the late 6th century with the Avars, a Mongol people seeking refuge from the Turks, provide an excellent example of this “defensive imperialism.” The Avar ambassadors reached Constantinople in 557, and, although they did not receive the lands they demanded, they were loaded with precious gifts and allied by treaty with the empire. The Avars moved westward from south Russia, subjugating Utigurs, Kutrigurs, and Slavic peoples to the profit of the empire. At the end of Justinian's reign, they stood on the Danube, a nomadic people hungry for lands and additional subsidies and by no means unskilled themselves in a sort of perfidious diplomacy that would help them pursue their objectives.

We encountered the Avars in Impearls' earlier article Crusades IV (permalink), when acting in concert with the invading Sasanian Persians (who had overrun Byzantium's Asiatic provinces), they besieged Constantinople, the “New Rome” and capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Persians were prevented from joining up across the Bosporus with the Avars, and both were thrown back (626), whereupon Avar influence was diminished to an extent that new powers, such as the Bulgarians, emerged on their flanks, while hosts of their slaves and serfs threw off their yoke (a fascinating story in its own right) — but Avar power did not disappear. Despite narrow escapes at the hands of the Romans, the core of the Avar realm remained intact, centered on the Hungarian plain, for most of the next two hundred years.

Historian Gerhard Seeliger describes, in The Cambridge Medieval History, the Avars' permanent facilities: 12

In the plain between the Danube and the Theiss were situated the “Rings” — the strong circular walls round extensive dwelling-places. According to the assertion of a Frankish warrior — quoted by the Monk of St Gall — the Rings extended as far “as from Zurich to Constance” (therefore about 60 kilometres or nearly 38 miles) and embraced several districts. In these Rings, of which, according to the Monk of St Gall, there were nine, the Avars had heaped their plunder of two centuries.

Late in the 8th century the Avars attempted to break the growing power of the Frankish Empire of Charles the Great (known to us as Charlemagne), by allying with the Frankish realm's most important enemies — Saxons and Saracens.

In the year 788 the Avars attacked the Empire, but were totally defeated.

Charles resolved to extirpate the Avar threat; he was delayed for several years — however,

In the year 795 the Margrave Erich of Friuli, supported by the Slav prince Woinimir, advanced over the Danube and took the principal Ring. Large treasures of gold made their way to the Franks, and even if the opinion is scarcely tenable that great changes in prices in the Frankish Empire were the result, still his success was great. In the following year Charles' son Pepin completed the work of conquest. He destroyed the Ring, subdued the Avars, and opened large districts to the preaching of Christianity. In later years small risings had still to be put down, and Frankish blood still flowed in battle against the barbarians. In 811 a Frankish army was sent against Pannonia. But these were only echoes of the past. The Avars themselves are mentioned for the last time in 822.

Assessment: Purely from a combination of attributes, the Avars must rank among the highest in overall resemblance to the Rohirrim. Their military equipment kit was largely the same as the Sarmatians — which is to say, very close to the Rohirrim — plus the stirrup was indubitably known by the Avars' time, so this aspect of their gear matches as well. Avars occupied “lands that had once been part of the domain of a neighboring culture that is both older and more highly developed,” — i.e., lands formerly belonging to the Roman Empire. They certainly possessed permanent residences and very substantial fortifications. (Thus the Avars really were, in their own special sense, “Lord of the Rings.”)

If the Avar — or, say, the Gothic — realm equals Rohan, what then is Gondor, that “neighboring culture that is both older and more highly developed”? Obviously Gondor must be the (diminished) Roman Empire! Which means that Minas Tirith is… Constantinople. Actually, this makes a lot of sense (smile). Though Constantinople doesn't ring a mountain, its walls do encircle (7) hills, and were indeed the most formidable city-wall fortifications — the only double wall — in history. Associating with fabulous Constantinople ought not dishonor Minas Tirith's name one whit!

(Perhaps someday Impearls will review Constantinople's amazing walls and defenses.

In the meantime see Impearls' article

Crusades II

[permalink]

for an appreciation of the Byzantine Empire.)

Thanks to the

University of Alabama at Birmingham

for their fine

Images from History

collection.

References

1 J. R. R. Tolkien, The Return of the King, being the Third Part of The Lord of the Rings, 1965, Second Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston; pp. 411-414.

2 William H. McNeill (Robert A. Millikan Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History, University of Chicago; author of The Rise of the West and others), “The History of the Eurasian Steppe: … Scythian successes,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

3 “Scythian,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

4 William H. McNeill (Robert A. Millikan Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History, University of Chicago; author of The Rise of the West and others), “The History of the Eurasian Steppe: … Scythian successes,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

5 Gavin R.G. Hambly (Professor of History, University of Texas at Dallas; coauthor and editor of Central Asia), “Central Asia: … History: … Early western peoples,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

6 Roman Ghirshman (died 1979; Archaeologist. Director General, French Archaeological Delegation to Iran, 1946-67), “Iran: History: … The “phil-Hellenistic” period (c. 171 BC-AD 10): Wars with Rome,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

7 “Goth,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

8 William H. McNeill (Robert A. Millikan Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History, University of Chicago; author of The Rise of the West and others), “The History of the Eurasian Steppe: … Geography of adjacent regions,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

9 “Ostrogoth,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

10 “Avar,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

11 John L. Teall (died 1979; Professor of History, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts, 1968-79; coauthor of Atlas of World History) and Donald MacGillivray Nicol (Koraës Professor Emeritus of Byzantine and Modern Greek History, Language, and Literature, King's College, University of London; Director, Gennadius Library, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1989-92; author of The Last Centuries of Byzantium and others), “The History of the Byzantine Empire: … The last years of Justinian I,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Britannica CD 1997, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

12

Dr. Gerhard Seeliger (Professor of Law in the University of Leipsic), Chapter XIX: “Conquests and Imperial Coronation of Charles the Great,” Volume II: The Rise of the Saracens and the Foundation of the Western Empire, edited by H. M. Gwatkin and J. P. Whitney, The Cambridge Medieval History, planned by J. B. Bury, 1913, Cambridge at the University Press; p. 609.

UPDATE: 2004-01-09 14:00 UT. Prof. Stephen Bainbridge has linked back to this piece with a note titled “More on the Rohirrim,” calling it, in an e-mail, “Great stuff!”

UPDATE: 2004-01-16 14:15 UT. Geitner Simmons in his Regions of Mind blog has enthusiastically linked to this ‘Rohirrim’ series of articles, commenting:

On another historical note, Michael McNeil of the blog Impearls has put together a terrific set of posts titled “‘Horsey’ Vikings — exploring origin of the ‘Rohirrim’ in The Lord of the Rings.” The series looks at Saracens and other assorted horse-riding warriors. I'm ill-equipped to debate points of arguments that Michael says have arisen over the Rohirrim. The link, by the way, goes [to] a post that features exquisite graphics to complement Michael's text.

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12