|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: GWAC: Introduction

Item page — this may be a chapter or subsection of a larger work. Click on link to access entire piece.

Earthdate 2009-12-15

| Introduction |

Most people forget the role Washington performed between the war (the Revolutionary War, where he played a decisive part in obtaining the victory), and his two terms as first President of the United States. Historian Allan Nevins wrote about that seeming hiatus, especially with regard to Washington's commanding presence as presiding officer at the Constitutional Convention, full of portent for the future: 1

Viewing the chaotic political condition of the United States after 1783 with frank pessimism and declaring (May 18, 1786) that “something must be done, or the fabric must fall, for it is certainly tottering,” Washington repeatedly wrote his friends urging steps toward “an indissoluble union.” At first he believed that the Articles of Confederation might be amended. Later, especially after the shock of Shays's rebellion, he took the view that a more radical reform was necessary but doubted as late as the end of 1786 that the time was ripe. His progress toward adoption of the idea of a federal convention was, in fact, puzzlingly slow. Though John Jay assured him in March 1786 that breakup of the nation seemed near and opinion for the convention was crystallizing, Washington remained noncommittal. But despite long hesitations, he earnestly supported the proposal for a federal impost, warning the states that their policy must decide “whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered a blessing or a curse.” And his numerous letters to the leading men of the country assisted greatly to form a sentiment favourable to a more perfect union. Some understanding being necessary between Virginia and Maryland regarding the navigation of the Potomac, commissioners from the two states met at Mount Vernon in the spring of 1785; from this seed sprang the federal convention. Washington approved in advance the call for a gathering of all the states to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787 to “render the Constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” But he was again hesitant about attending, partly because he felt tired and infirm, partly because of doubts about the outcome. Although he hoped to the last to be excused, he was chosen one of Virginia's five delegates.

Washington arrived in Philadelphia on May 13, the day before the opening of the Convention, and as soon as a quorum was obtained he was unanimously chosen its president. For four months he presided over the Constitutional Convention, breaking his silence only once upon a minor question of congressional apportionment. Though he said little in debate, no one did more outside the hall to insist on stern measures. “My wish is,” he wrote, “that the convention may adopt no temporizing expedients, but probe the defects of the Constitution to the bottom, and provide a radical cure.” His weight of character did more than any other single force to bring the convention to an agreement and obtain ratification of the instrument afterward. He did not believe it perfect, though his precise criticisms of it are unknown. But his support gave it victory in Virginia, where he sent copies to Patrick Henry and other leaders with a hint that the alternative to adoption was anarchy, declaring that “it or dis-union is before us to chuse from,” told powerfully in Massachusetts. He received and personally circulated copies of The Federalist. When ratification was obtained, he wrote to leaders in the various states urging that men staunchly favourable to it be elected to Congress. For a time he sincerely believed that, the new framework completed, he would be allowed to retire again to privacy. But all eyes immediately turned to him for the first president. He alone commanded the respect of both the parties engendered by the struggle over ratification, and he alone would be able to give prestige to the republic throughout Europe. In no state was any other name considered. The electors chosen in the first days of 1789 cast a unanimous vote for him, and reluctantly — for his love of peace, his distrust of his own abilities, and his fear that his motives in advocating the new government might be misconstrued all made him unwilling — he accepted.

We will essay to explore further what is already apparent from Nevins's exposition of Washington: the critical importance for the history of American and the world of character.

For insight in this regard, let's turn to that delightful collection of fantasy dinner conversations with great personages of history Van Loon's Lives, published 1942 — prepared for the edification and inspiration of his grandchildren by Dutch-American historian and journalist Hendrik Willem van Loon, who arrived on America's shores in 1903 at the tender age of 19.

In the foreword to his imaginary dinner with both William of Orange (known as the Silent; founder of the 16th-century Dutch Republic, whose declaration of independence from the Habsburg Spanish Empire, the Act of Abjuration, left reverberations echoing down through history to our own Declaration of Independence), as well as George Washington (father some two centuries after William of America's Republic), van Loon ended his introduction to Washington's life (which we'll soon consider in detail) with the following penetrating comment: 2

[I]t was he who founded our republic; it was this Virginian planter who set us free from foreign domination; it was this Southern aristocrat who started us off on our noble experiment in self-government, and he was able to do this because he was far ahead of his contemporaries in that one particular respect which counts more heavily in the scales of the gods than all other qualifications for glory and success put together.

George Washington was the embodiment of character.

Webster defines character as follows: ”Highly developed or strongly marked moral qualities; individuality, esp. as distinguished by moral excellence; moral vigor or firmness, esp. as acquired through self-discipline; inhibitory control of one's instinctive impulses….”

I think that I can let it go at that. For my final comment upon both William of Orange and George Washington need consist of but one single word: CHARACTER.

We've already pointed to Washington's critical role in the drafting and ratification of the Constitution, which may also be attributed to the force of his character on the Convention and country. But there is another aspect in which Washington's character had a terrific impact on the future of the fledgling nation, and that is the manner in which he departed the office of Presidency.

One should observe that in all the centuries-long history of the Roman Empire (so analogous to America in certain ways, but in this respect so totally different) there was only a single emperor — to wit, Diocletian (regnant 284-305 a.d.) — who managed at the end of his reign to retire and devote the remainder of his days to gardening. * All other emperors of the Empire either died in office or were bloodily overthrown.

(*Diocletian's retirement palace — one can see an illustration of what it looked like here — over time transformed into the ancient historical core of the modern Adriatic coastal city of Split in Croatia.)

Washington retired from office after only two terms, less than a decade. He could have run again, but chose not to, setting a lasting, shining example for future American Presidents — whose tradition continued unbroken until, with World War II raging abroad, Franklin Roosevelt chose to stand for a third, and then a fourth term. (After the war, a constitutional amendment enforcing a two-term limit was ratified.)

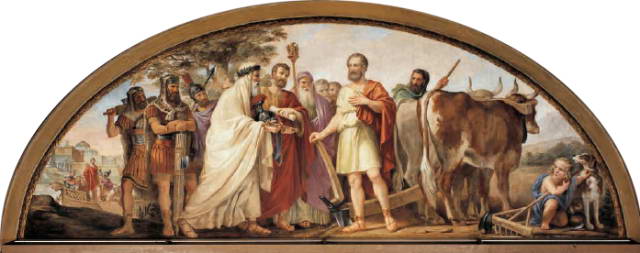

Washington and the Founders went even further in emphasizing a specifically Roman counterexample in an attempt to offset any tendency toward military instability such as Roman history so well exemplified, by creating an official association of Revolutionary War officers — the Society of Cincinnati — explicitly inspired by the Roman citizen-farmer Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (born circa 519 b.c.), who became Roman Consul and then (emergency) Dictator, but after the foe was vanquished, retired once again to his farm.

Washington and subsequent Presidents' example was such a success that nothing like a military rebellion has ever occurred in U.S. history.

And still, even today, America continues to transition authority wholly peacefully from one President to the next — in what is really a revolution: every election in a democracy is a revolution — an entirely peaceful revolution — yet one so many people in this country blithely take wholly for granted.

For me, though, given the stark precedents from Roman history, whenever I see each peaceful transfer of power occur, I consider it almost a miracle.

|

Labels: Allan Nevins, American history, ancient Rome, apotheosis, constitution, George Washington, Hendrik Willem van Loon, Revolutionary War, United States of America, William of Orange (the Silent)

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12

0 comments: (End) Post a Comment