|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: 2009-12-13 Archive

Earthdate 2009-12-15

| George Washington – Apotheosis of Character |

|

|

Enthroned above a rainbow (in Constantino Brumidi's stunning masterpiece “The Apotheosis of Washington”), the deified George Washington — first President of the United States and acclaimed as “father of his country” — regards us from on high as the Lord of Hosts and Supreme Judge of the Universe. With a gesture at the Law/Constitution on the one hand, upraising a downturned sword with the other — flanked by the goddesses of Liberty (grasping the traditional Roman fasces of authority) and Victory/Fame (cradling a palm of victory whilst flourishing the clarion of fame) — the apotheosized Washington sits haloed by a constellation of thirteen Starry maidens, hoisting a banner proclaiming E Pluribus Unum.

Round about that scene (starting at bottom, thence proceeding clockwise) are depicted tableaus of

War,

Science,

“Marine,”

Commerce,

Mechanics,

and

Agriculture — occupying the crown of the great dome arching above the Capitol, within whose hallowed halls the Congress of the United States sits and holds session.

|

This year (2009) marks the 210th anniversary of the passing (on earthdate 1799-12-15) of the man who, first as a general in war, won the freedom of the people of the United States of America; thereafter in peace (after the ignominious failure of the first American constitution, the Articles of Confederation) presided by acclamation over the Constitutional Convention, which — composed of all-time exceptionally clear-headed political thinkers — drafted the Constitution of the United States, still in effect today (a monumental accomplishment compared with the experience of almost every other country in the world); finally serving two terms as the first constitutional President of the unified American nation. Beyond those stupendous achievements was his final voluntary withdrawal after those elected terms of office, retiring to his Mount Vernon estate and removing himself entirely from subsequent politics — which, one might judge, due to the outstanding example presented to his successors and to posterity, as equal to all the preceding actions of his eventful career. These acts made Washington the stuff of legend — an almost deliberate hearkening back to Republican Rome in its grandeur.

Nowadays, following the turn of the 21st century, the extraordinary devoted homage earlier eras in America paid to its founding General and President seems more than a bit mysterious. Portrayals of Washington in powdered wig and the 18th century elite attire of the day present a notably quaint appearance today, and though founder of the U.S.A. (which somehow in retrospect seems a very easy thing to do, even foreordained), really — so the “modern,” irreverent trendy line of thought goes — what did he do that was so all-fired great? Folk today typically know little of the period or the man, so nothing (or very little) is usually the implied answer — and since most folks' dilettantish inquiries seldom go further, that's usually the end of their investigation.

However, after ten score and ten years it's high time in my view for people to once again begin to reacquaint themselves with the great man and the impact, the effect the sheer force of his character has had, on America and indeed the history of the world.

Labels: Allan Nevins, American history, ancient Rome, apotheosis, constitution, George Washington, Hendrik Willem van Loon, Revolutionary War, United States of America, William of Orange (the Silent)

| Chapter Index |

Van Loon's Washington

- Introduction by Michael McNeil

- Tectonic Movements

- The Washingtons and Washington

- War in the Wilderness

- Martha Dandridge Custis

- The Cromwellian Sequel

- Apotheosis

- References and Figures

- Updates

- End

| Introduction |

Most people forget the role Washington performed between the war (the Revolutionary War, where he played a decisive part in obtaining the victory), and his two terms as first President of the United States. Historian Allan Nevins wrote about that seeming hiatus, especially with regard to Washington's commanding presence as presiding officer at the Constitutional Convention, full of portent for the future: 1

Viewing the chaotic political condition of the United States after 1783 with frank pessimism and declaring (May 18, 1786) that “something must be done, or the fabric must fall, for it is certainly tottering,” Washington repeatedly wrote his friends urging steps toward “an indissoluble union.” At first he believed that the Articles of Confederation might be amended. Later, especially after the shock of Shays's rebellion, he took the view that a more radical reform was necessary but doubted as late as the end of 1786 that the time was ripe. His progress toward adoption of the idea of a federal convention was, in fact, puzzlingly slow. Though John Jay assured him in March 1786 that breakup of the nation seemed near and opinion for the convention was crystallizing, Washington remained noncommittal. But despite long hesitations, he earnestly supported the proposal for a federal impost, warning the states that their policy must decide “whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered a blessing or a curse.” And his numerous letters to the leading men of the country assisted greatly to form a sentiment favourable to a more perfect union. Some understanding being necessary between Virginia and Maryland regarding the navigation of the Potomac, commissioners from the two states met at Mount Vernon in the spring of 1785; from this seed sprang the federal convention. Washington approved in advance the call for a gathering of all the states to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787 to “render the Constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” But he was again hesitant about attending, partly because he felt tired and infirm, partly because of doubts about the outcome. Although he hoped to the last to be excused, he was chosen one of Virginia's five delegates.

Washington arrived in Philadelphia on May 13, the day before the opening of the Convention, and as soon as a quorum was obtained he was unanimously chosen its president. For four months he presided over the Constitutional Convention, breaking his silence only once upon a minor question of congressional apportionment. Though he said little in debate, no one did more outside the hall to insist on stern measures. “My wish is,” he wrote, “that the convention may adopt no temporizing expedients, but probe the defects of the Constitution to the bottom, and provide a radical cure.” His weight of character did more than any other single force to bring the convention to an agreement and obtain ratification of the instrument afterward. He did not believe it perfect, though his precise criticisms of it are unknown. But his support gave it victory in Virginia, where he sent copies to Patrick Henry and other leaders with a hint that the alternative to adoption was anarchy, declaring that “it or dis-union is before us to chuse from,” told powerfully in Massachusetts. He received and personally circulated copies of The Federalist. When ratification was obtained, he wrote to leaders in the various states urging that men staunchly favourable to it be elected to Congress. For a time he sincerely believed that, the new framework completed, he would be allowed to retire again to privacy. But all eyes immediately turned to him for the first president. He alone commanded the respect of both the parties engendered by the struggle over ratification, and he alone would be able to give prestige to the republic throughout Europe. In no state was any other name considered. The electors chosen in the first days of 1789 cast a unanimous vote for him, and reluctantly — for his love of peace, his distrust of his own abilities, and his fear that his motives in advocating the new government might be misconstrued all made him unwilling — he accepted.

We will essay to explore further what is already apparent from Nevins's exposition of Washington: the critical importance for the history of American and the world of character.

For insight in this regard, let's turn to that delightful collection of fantasy dinner conversations with great personages of history Van Loon's Lives, published 1942 — prepared for the edification and inspiration of his grandchildren by Dutch-American historian and journalist Hendrik Willem van Loon, who arrived on America's shores in 1903 at the tender age of 19.

In the foreword to his imaginary dinner with both William of Orange (known as the Silent; founder of the 16th-century Dutch Republic, whose declaration of independence from the Habsburg Spanish Empire, the Act of Abjuration, left reverberations echoing down through history to our own Declaration of Independence), as well as George Washington (father some two centuries after William of America's Republic), van Loon ended his introduction to Washington's life (which we'll soon consider in detail) with the following penetrating comment: 2

[I]t was he who founded our republic; it was this Virginian planter who set us free from foreign domination; it was this Southern aristocrat who started us off on our noble experiment in self-government, and he was able to do this because he was far ahead of his contemporaries in that one particular respect which counts more heavily in the scales of the gods than all other qualifications for glory and success put together.

George Washington was the embodiment of character.

Webster defines character as follows: ”Highly developed or strongly marked moral qualities; individuality, esp. as distinguished by moral excellence; moral vigor or firmness, esp. as acquired through self-discipline; inhibitory control of one's instinctive impulses….”

I think that I can let it go at that. For my final comment upon both William of Orange and George Washington need consist of but one single word: CHARACTER.

We've already pointed to Washington's critical role in the drafting and ratification of the Constitution, which may also be attributed to the force of his character on the Convention and country. But there is another aspect in which Washington's character had a terrific impact on the future of the fledgling nation, and that is the manner in which he departed the office of Presidency.

One should observe that in all the centuries-long history of the Roman Empire (so analogous to America in certain ways, but in this respect so totally different) there was only a single emperor — to wit, Diocletian (regnant 284-305 a.d.) — who managed at the end of his reign to retire and devote the remainder of his days to gardening. * All other emperors of the Empire either died in office or were bloodily overthrown.

(*Diocletian's retirement palace — one can see an illustration of what it looked like here — over time transformed into the ancient historical core of the modern Adriatic coastal city of Split in Croatia.)

Washington retired from office after only two terms, less than a decade. He could have run again, but chose not to, setting a lasting, shining example for future American Presidents — whose tradition continued unbroken until, with World War II raging abroad, Franklin Roosevelt chose to stand for a third, and then a fourth term. (After the war, a constitutional amendment enforcing a two-term limit was ratified.)

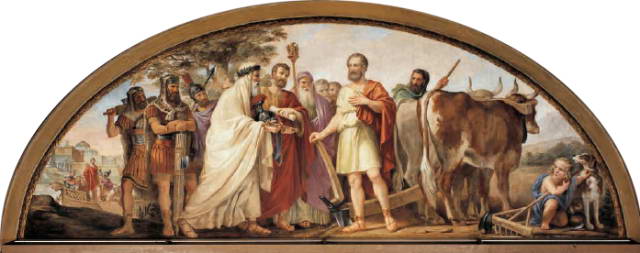

Washington and the Founders went even further in emphasizing a specifically Roman counterexample in an attempt to offset any tendency toward military instability such as Roman history so well exemplified, by creating an official association of Revolutionary War officers — the Society of Cincinnati — explicitly inspired by the Roman citizen-farmer Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (born circa 519 b.c.), who became Roman Consul and then (emergency) Dictator, but after the foe was vanquished, retired once again to his farm.

Washington and subsequent Presidents' example was such a success that nothing like a military rebellion has ever occurred in U.S. history.

And still, even today, America continues to transition authority wholly peacefully from one President to the next — in what is really a revolution: every election in a democracy is a revolution — an entirely peaceful revolution — yet one so many people in this country blithely take wholly for granted.

For me, though, given the stark precedents from Roman history, whenever I see each peaceful transfer of power occur, I consider it almost a miracle.

|

Labels: Allan Nevins, American history, ancient Rome, apotheosis, constitution, George Washington, Hendrik Willem van Loon, Revolutionary War, United States of America, William of Orange (the Silent)

|

Tectonic Movements

|

|

And now a few words about General George Washington, but so much has been written about him that I can be very short.

Within the realm of geology it sometimes happens that one layer of rock will push itself across another layer, and then it takes an expert to determine exactly what has taken place. The same holds good for history. Not infrequently it occurs that some particular cultural or economic or social layer shifts from one part of the world to another, but as a rule this takes place so quietly and so gradually that hardly anybody notices the change. Then the denuded soil at home develops a new civilization entirely different from the old one, but that too comes about so slowly that it attracts few people's attention. Until the fatal day when the people wake up to a realization that, though nominally they still speak the same language, are still loyal to the same flag, and are still supposed to worship the same God, they have no longer anything in common with each other. After that the more they try to explain themselves and their motives to their former neighbors, the less they succeed in doing so.

Take our own case. We are only beginning to suspect what happened during the seventeenth century in regard to the old England and the new one. The peace which had finally made an end to the great Lutheran-Catholic controversy had decreed that every prince should have the right to decide what form of religious worship his subjects must accept. That, of course, had been one of those “compromises of desperation” which are the result of an intolerable situation. Europe could not possibly survive if the people continued to destroy each other on account of their religious convictions. Any kind of arrangement, guaranteeing at least a momentary respite from the everlasting slaughter, was better than a continuation of the war, and the disastrous principle of “whose rule I accept, his God I also worship” was greeted as a very clever solution, worthy of the support of all good citizens and not to be questioned or debated any longer.

But in reality, the compromise was just another Trojan horse, filled with the partisans of totalitarianism, and after they had clambered out of their uncomfortable hiding place and had stretched their arms and legs, they descended upon the peaceful denizens of every town and hamlet in Europe and put before them the choice either of accepting the tyranny of their new masters or of being hanged in their own doorways.

It was then that the old Continent was delivered over to the mercies of a dozen competing dynasties, and it was then that the last remnants of medieval self-government were threatened with complete destruction. Here and there, in a few of the Swiss cantons and a few of the Dutch provinces, people continued to rule themselves (to a certain extent, for money, as it has always done, counted heavily in politics), and it was then that England made her noble and glorious effort to establish the supremacy of Parliament over the pretensions of the crown.

I am expressing myself perhaps a little too modernly. The medieval belief in an omnipotent God and in an equally omnipotent source of worldly authority was still part of the spiritual and intellectual make-up of most people. The King was still revered as the God-anointed embodiment of all terrestrial authority and therefore above criticism. Even the Act of Abjuration, which had curtly dismissed King Philip of Spain as ruler over the Low Countries because he had been an unfaithful shepherd unto his flocks, continued to be regarded by many people as something that interfered much too boldly with the orderly progress of a universe in which it stood decreed that a few were predestined to command while the rest must obey.

However, there now were definite precedents for a different approach to this subject, and the people of England were the first to make use of them. Hence, a prolonged struggle between the crown and its subjects. Good Queen Bess may have been just as much of a tyrant at heart as her dear cousin, Mary of Scotland, but she was too shrewd to reveal her true feelings. She knew how to temper her authoritative instincts with acts of good-humored bonhomie (is there a feminine equivalent for this expression?), and if occasionally she spanked her children, they accepted it good-naturedly enough. What was the use of having such a sweet and loving mother if now and then she could not lose her temper with her brood and treat them to a few slaps and cuffs?

But after the old lady had departed this life and had been succeeded by the son of Cousin Mary, a great change came over this Merrie England. The Stuarts now moved from Edinburgh to London, but being Scotchmen they never quite understood their English subjects, and, with their arrival in the British capital, there came a change over the land that led up to that half a century of constant friction which in turn was to lay the foundations for the free and independent United States of America. For those elements in England's life which foresaw what was coming despaired of maintaining the liberties and prerogatives they needed in order to function properly and happily and, as there seemed to be no chance of getting rid of their imported Scots monarchs, they began to look for another place of abode where they might continue to live their own kinds of lives without being constantly exposed to a visit from the local sheriff and a polite invitation to hie themselves to the Tower, there to await His Majesty's pleasure and (most likely) his executioner.

When an exasperated nation at last grew tired of their rulers and sent for Dutch William to put their house in order, there seemed to be a chance that all would now be well. Unfortunately, headachy William did not even live as long as Oliver Cromwell, and a dozen years after his death the British crown fell into the hands of a minor German dynasty that had to spend two centuries in its adopted country before it finally lost its guttural Teutonic accent and could express itself more or less adequately in the tongue of William Shakespeare. From a merely political point of view, therefore, little was gained when the House of Hanover succeeded that of Stuart, and gradually there came about such a hopeless cleavage between the England of the Old World and that of the New that only a war could decide the issue. That war became known as the American Revolution, and it gave us our own republic.

|

The Washingtons and Washington

|

|

The ancestors of George Washington came from Northamptonshire. The moved to the New World in 1658, when George's great-grandfather bade farewell to England's white cliffs and settled down near Bridges Creek, in Virginia. We know little about him, except that he continued to follow the sort of career he would have chosen in the Old World and became a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. He died in 1676, leaving his meager estates to his son Lawrence.

Lawrence's second son, Augustine, having been born on this side of the ocean, felt more at home among his new surroundings than his father had done. He caught the spirit of the new country and saw more profit in running an iron mine and an iron smelter than in doing what all the members of his tribe had done. Thus far they had contented themselves with raising tobacco for the London market — a rather hazardous venture, as it placed them completely at the mercies of their British agents.

Digging iron out of the soil was, of course, not quite as genteel a profession as supervising lazy and unwilling Negro slaves, but it was much more profitable, and after he had returned from his schooling in England, Augustine had settled down near Fredericksburg and in due course of time had married two wives (one after the other, of course), by the second of whom, Mary Ball, he had six children, the oldest of whom was baptized George.

The boy grew up in the normal way of that period. The local sexton taught him his letters, and afterward a schoolmaster was hired to give the young gentleman a smattering of Latin. Mathematics, for which Master George felt a great liking, was not on the regular curriculum of the Virginia educational system of the middle of the eighteenth century (George was born in 1732), and so he was obliged to go after it on his own account. He later extended his scientific researches into the realm of practical surveying, and this knowledge of how to make and read maps was of the greatest value to him when he was called upon to lead the armies of the rebellious colonists.

It was a time when boys of fourteen were supposed to be able to shift for themselves. In consequence, his half brother Augustine, who had been the head of the family ever since their father's death and who recognized that George had the makings of an excellent manager, entrusted him with the care of several plantations at an age when a modern youngster has not even thought of choosing a career. George liked his new life, for it meant action. He was forever on the move, examining accounts, hiring and firing overseers, buying and selling crops and slaves, learning all about tobacco, experimenting with new kinds of cattle, and in a general way making himself useful until, at the ripe old age of seventeen, he was deemed fit for public office and was appointed assistant public surveyor of Fairfax County. This favor was bestowed upon him by the amiable Thomas, Lord Fairfax, who, having acquired a trifling five million acres in the Shenandoah Valley, had at last decided to cross the ocean and inspect his property in person. He was now living on a fine estate along the Potomac, not far away from that plantation where John, the first Washington in America, had started the family's fortunes.

It was during this period as a public surveyor that Washington became thoroughly familiar with life in the wilderness and got some conception of the vastness of this new world in which the colonists, until then, had stuck anxiously to the narrow strip of land along the seaboard. But these carefree years, which he probably enjoyed as well as any other part of his career, came abruptly to an end in 1752, when his half-brother Lawrence died.

The Washingtons as a family were apt to have weak chests, and Lawrence had never recovered from the hardships of his campaign against the Spanish city of Cartagena, in what is now the republic of Colombia, in South America. There he had served with the fleet, and the fleet had been commanded by that Admiral Edward Vernon who as “Old Grog” won everlasting detestation in the British navy by ordering that the sailors should not get their rum straight but mixed with water so that they should not be incapacitated quite as much of the time as they used to be, when the stuff was poured raw down their throats.

This expedition against Cartagena had not accomplished much toward making England mistress of the Caribbean (through no fault of Vernon's, but because of the incompetence of most of his colleagues), but out of it had grown that friendship between Lawrence Washington and his commander in chief which made Lawrence change the name of Little Hunting Creek plantation to Mount Vernon.

As I just said, Lawrence died in 1752. He left Mount Vernon to his widow, Anne Fairfax, who within the same year married into the Lee family. She sold the estate to her brother-in-law George, who, then at the age of thirty, began that career of a sound marriage and shrewd investments which eventually was to make him one of the richest young men of Virginia.

But in the meantime, George had done several other things which were to prepare him still further for the role he would soon afterward be called upon to play.

|

War in the Wilderness

|

|

In the year 1753 Governor Dinwiddie had appointed him a major and had sent him into the wild West with orders to find the commander of the French forces, who, after an overland voyage from Canada, had occupied the greater part of the Ohio Valley. Major Washington was to remind his French colleague that he was poaching on British territory and to suggest that he leave as soon as possible.

Whether on this occasion Washington was guided by his own woodcraft, by divine Providence, or by his interpreter, Jacob Vanbraam, I could not tell you, but Washington did find the man he was looking for and delivered his message. The Frenchman courteously invited him to dinner in a fort which is now the town of Waterford, in Pennsylvania, but added that for the present, at least, he and his French troops intended to remain where they were.

This refusal on the part of the French to withdraw their forces led to skirmishes, and these skirmishes in turn led to war. During this conflict Washington, badly supported by the undisciplined colonial troops, was taken prisoner by the French and was only released after he had signed a promise that the British would not try to build any other fortifications in the Ohio Valley for at least a year.

After the failure of their irregular troops, the London authorities hoped to have better luck with their regulars. In February, 1755, General Edward Braddock arrived in Virginia. Washington, like most of the other native officers, had withdrawn from army life. The reason for such a step? These American-born fighters resented being treated as “colonials.” No “colonial” officer could receive the same pay as one born in the old country, and any colonial officer, no matter what rank he held, was supposed to be inferior to a mere youngster who held a direct commission from the King.

It was that sort of thing — that irrepressible habit of all good Britishers to act in a superior manner toward all non-Britishers — which had more to do with the outbreak of the American Revolution than all the taxes on tea and all the stamps on official documents. But England was not to learn this until more than a century and a half later.

Heaven knows, these colonials had no reason to feel inferior toward their London superiors. General Braddock, in spite of his personal bravery, was as ignorant of wilderness warfare as the commander of the Horse Guards, a hundred years later, was to be unfamiliar with the topography of the territory around Balaklava. And if it had not been for George Washington (who at the last moment had once more taken to the field, probably anticipating what was going to happen), hardly a man of that British expeditionary force would have come back alive.

In consequence whereof, Colonel Washington was appointed to the post of commander in chief of all the Virginia troops. Did all this teach the British regulars their lesson? It did not. For when George Washington, holder of a colonial appointment, told a mere captain with a royal commission to do something he wanted done, the captain told him to go jump into the lake. And Washington was obliged to travel all the way to Boston, where the British commander in chief was stationed, to get redress for this insult.

This time he won out, but it was that sort of inexcusable stupidity and arrogance which kept the colonials in a constant state of irritation.

It is quite understandable that the Virginian, whose health had been greatly impaired by his campaign in the wilderness, used the first possible opportunity to resign his commission and refused to have anything further to do with British officialdom.

From then on he was going to enjoy the quiet life of a plantation owner, and the world, whether sober or drunk, could pass by his door — it was to be no concern of his what happened to it.

A military lean-to in the forest was at best a pretty poor sort of makeshift, where as a home of his own in his beloved Virginia would allow him to forget the hardships and discomforts of his earlier days in the field.

|

|

Martha Dandridge Custis

|

|

|

|||

|

Of course, one could not very well administer a plantation without a wife. But suitable wives were hard to find, and furthermore, George Washington had never been very successful with the ladies. This, in spite of his six feet and his perfect willingness to adapt himself completely to the customs and habits of the society into which he happened to have been born and to partake of all the fashionable pleasures of that day, such as dancing, hunting, riding, drinking, and going to Sunday service in the nearest Episcopal church.

But, as most of us six-footers know only too well, women, being what they are, prefer the little fellows whom they can pick up when they fall and hurt themselves and whom they can carry away in their arms and fondle until they smile again and are able to say, “I am feeling much better, and now I will go and pluck you a daisy.”

George Washington was no daisy plucker. A young man who before his twenty-fourth year had gone through a couple of wilderness campaigns, who had fought in half a dozen battles, and who had experienced a great deal of sickness was apt to be a rather serious person, and that, of course, did not help him very much either while trying to win the favor of some Virginia belle. Finally, in sheer exasperation he decided to be practical rather than romantic, and he married the widow of a fellow planter, one Colonel Daniel Parke Custis. Martha Dandridge Custis was the mother of two children and the owner of fifteen thousand acres of land near Williamsburg, sixty-five thousand dollars in cash in the bank, and one hundred and fifty slaves. Martha Custis also was (and was to prove herself even more so in the years to come) a very kindhearted and understanding companion, an excellent housekeeper, and a discreet and faithful wife to a man who was to occupy the highest position in the land. Best of all (the only real consideration in such matters), she gave her husband everything he most cared for. She provided him with a well-run home, where at any time he could entertain all the friends he wanted to bring, and she saved him from all those fussy details which are so exasperating to a man who has got a real job to do.

Fifteen years after their marriage, George Washington came at last into his own. For he was given the task of reorganizing the new England on our side of the ocean into a nation that would be able to take over when the older England overseas should have failed.

|

The Cromwellian Sequel

|

|

The rest is history. It has been told so often and so well that I shall not waste your time repeating what all of us know. In England no one connected with the government seemed to have grasped the fact that the crown was dealing with a people who were the spiritual descendants of those Englishmen who, a century and a half before, had already rid themselves of one head bearing a crown. There is a story current in many parts of New England of how, during a threatened Indian massacre, there suddenly appeared an old, white-haired fellow, coming from nowhere in particular but wearing an outmoded Cromwellian uniform and wearily but efficiently swinging an old Cromwellian sword with which he promptly slew so many of the savages that the others fled in panic and were never again seen. Having saved his fellow settlers by his unexpected arrival, the white-haired, white-bearded hero silently withdrew into the dark fringe of the near-by forest and never again showed himself to mortal eye.

There was more truth to this bit of folklore than most people suspected. The number of regicide judges and other fugitives from Charles Stuart's revenge who had actually lost themselves in the American wilderness to find safety was probably very small. But their spirit was everywhere, and it lay hidden in the souls of a great many people who were completely unconscious of being anything but good, loyal subjects of His Majesty the King. Had a clever man ruled over England just before our Revolution, or even a merely mediocre one, capable at least of surrounding himself with wise counselors, all might have yet been saved, and the Revolution could probably have been avoided. But by this time the real rulers of England had been petrified into an aristocracy — into a rigid caste — and the country squire had so completely lost touch with the realities of daily existence that the world for him did not really begin except at five hundred pounds a year. How could those insular port drinkers and fox hunters, who only went abroad for the purpose of returning home infinitely more self-satisfied than they had left, ever had been made to understand that old Oliver Cromwell's ideas were still stirring among the spiritual descendants of those preposterous dissenters who had dared to lift their blasphemous hands against the sacred person of their anointed Majesty and who — serve them right! — had been taught a lesson when the body of their abominable leader had been dug out of its grave and had been thrown to the dogs.

That much was true.

The remains of the great Oliver no longer rested in the chapel of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey, but his soul had gone marching on.

It continued to march on for six long and desperate years, until that ever-fateful nineteenth of October of the year 1781, when General George Washington of Mount Vernon in Virginia, commander in chief of the armies of the United States of America, courteously bowed to Major General Charles Cornwallis, commander in chief of His Majesty's forces in South Carolina, and told that dejected gentleman to keep his sword, for he had been a brave foeman, and the code of honor of their common heritage demanded that one behave generously toward a conquered enemy who had fought the good fight squarely and decently and who had behaved as modestly and decorously in victory as in defeat.

|

|

Apotheosis

|

|

With this little anecdote, I think I can bid the General farewell, for you will now understand what kind of person he was. And now that all the evidence is available, we can sum him up in a very few words, for there really was nothing very complicated about this greatest of all Americans.

George Washington was not a great military leader. He was careful and methodical, but he lacked the genius of an Alexander or a Napoleon. He was not a creative statesman like Jefferson, and old Ben Franklin was his undisputed master when it came to diplomatic negotiations that required shrewdness and patience and a gift for horse trading. As an orator he was deplorably lacking in all those tricks by which an experienced speaker can sway his audiences. Nor did he ever indulge in what we would now call original and creative thinking. He was by nature a conservative and deeply distrusted the bright boys who tried to sell him the ideal of the French Revolution. Indeed, if he had had his way, all radicals would have been sent back right away to where they had come from. They upset his notions about a well-regulated commonwealth in which every man, woman, child, horse, and dog should know his, or her, or its place in society. He wanted freedom, but it was the freedom that had prevailed in the England of his ancestors. The conception of liberty which was to arise soon afterward among the disinherited masses of the future republic he did not understand at all, and it is doubtful whether it would have been very much to his liking.

Yet, it was he who founded our republic; it was this Virginian planter who set us free from foreign domination; it was this Southern aristocrat who started us off on our noble experiment in self-government, and he was able to do this because he was far ahead of his contemporaries in that one particular respect which counts more heavily in the scales of the gods than all other qualifications for glory and success put together.

George Washington was the embodiment of character.

Webster defines character as follows: “Highly developed or strongly marked moral qualities; individuality, esp. as distinguished by moral excellence; moral vigor or firmness, esp. as acquired through self-discipline; inhibitory control of one's instinctive impulses….”

I think that I can let it go at that.

For my final comment upon both William of Orange and George Washington need consist of but one single word:

CHARACTER.

|

| References and Figures |

1 Allan Nevins (1890−1971; Senior Research Associate, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California, 1958−1969; Dewitt Clinton Professor of History, Columbia University, 1931−1958; author of The American States During and After the Revolution, The Emergence of Modern America, and many biographies), “George Washington,” Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008 Standard Edition.

2 Hendrik Willem van Loon (1882−1944), Van Loon's Lives: Being a true and faithful account of a number of highly interesting meetings with certain historical personages, from Confucius and Plato to Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson, about whom we had always felt a great deal of curiosity and who came to us as our dinner guests in a bygone year, written and illustrated by Hendrik Willem van Loon, 1942, Simon and Schuster, New York; pp. 110−111.

3

Hendrik Willem van Loon

(1882−1944),

Van Loon's Lives: Being a true and faithful account of a number of highly interesting meetings with certain historical personages, from Confucius and Plato to Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson, about whom we had always felt a great deal of curiosity and who came to us as our dinner guests in a bygone year, written and illustrated by Hendrik Willem van Loon, 1942, Simon and Schuster, New York; pp. 100−111.

Dinner conversation (not quoted): pp. 111−127.

f1 Constantino Brumidi (1805−1880), “The Apotheosis of Washington” (1865), Capitol of the United States, Washington, D.C.

f2 Constantino Brumidi (1805−1880), Detail: George Washington as Lord of Hosts and Supreme Judge of the Universe, from “The Apotheosis of Washington” (1865), Capitol of the United States, Washington, D.C.

f3 Constantino Brumidi (1805−1880), “Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus,&rdquo Capitol of the United States, Washington, D.C.

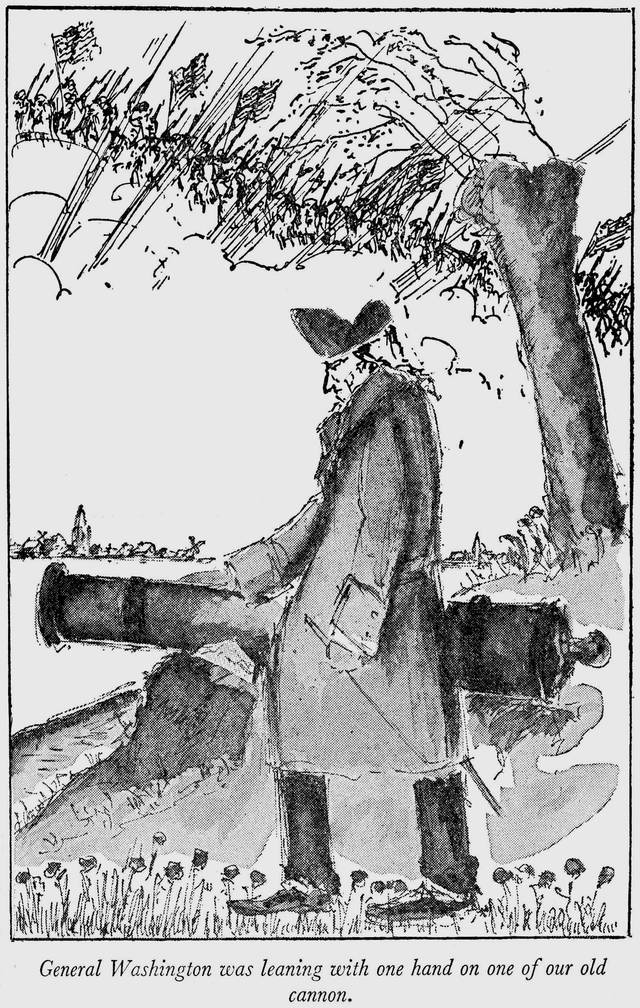

f4 Hendrik Willem van Loon (1882−1944), “General George Washington,” from Van Loon's Lives: Being a true and faithful account of a number of highly interesting meetings with certain historical personages, from Confucius and Plato to Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson, about whom we had always felt a great deal of curiosity and who came to us as our dinner guests in a bygone year, written and illustrated by Hendrik Willem van Loon, 1942, Simon and Schuster, New York; p. 117.

f5 Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741−1828), “George Washington” (1788), located in Virginia state capitol, Richmond. Original image file is here. “In Richmond stands a marble statue of George Washington that is among the most notable pieces of eighteenth-century art, one of the most important works in the nation, and, some think, the truest likeness of perhaps the first American to become himself an icon.”

f6 Charles Willson Peale (1741−1827), “George Washington in 1772,” hanging in Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia. Image from Wikipedia: George Washington in the French and Indian War; image page is here; image file here.

f7 Antonio Canova (1757−1822), “George Washington” in the garb of a Roman soldier (1820), located in North Carolina state capitol, Raleigh. The original image file is here.

f8 Charles Willson Peale (1741−1827), “George Washington in 1776” and “Martha Washington in 1776,” images from George Washington's Mount Vernon – Estate and Gardens, specifically from Paintings & Sculpture (obsolete page).

f9 Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze (1816−1868), “Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth”; image is here.

f10 Constantino Brumidi (1805−1880), “Surrender at Yorktown” (1865), Capitol of the United States, Washington, D.C.

f11 Horatio Greenough (1805−1852), “Washington as Zeus” (1832−1841), now on display at the Smithsonian Institute, National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C. Many thanks to Flickr user wallyg for the photograph; search to find similar Horatio Greenough photos by wallyg; particular photo is here.

f12 Constantino Brumidi (1805−1880), Detail: E Pluribus Unum, from “The Apotheosis of Washington” (1865), Capitol of the United States, Washington, D.C.

| Updates |

UPDATE: 2009-12-20 17:30 UT: Eric Scheie at his Classical Values blog posts a piece titled “210 years ago…” pointing to Impearls' article, and noting: “It is no exaggeration to say that George Washington's leadership of the country in its infancy has ensured that we have never had an emperor, dictator or military coup. His importance cannot be underestimated” [presumably he means “overestimated” here], “and it's never too late to learn why.” “Simply go to Michael McNeil's blog, check out his own essays, scroll down to read Van Loon's Washington and look at some wonderful images.” Thanks, Eric!

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12