|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: Greater Armenia - Little Armenia and Aftermath

Item page — this may be a chapter or subsection of a larger work. Click on link to access entire piece.

Earthdate 2004-06-26

| Little Armenia and Aftermath by Frédéric Macler |

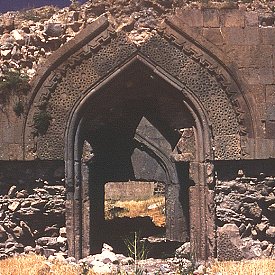

The national history of Greater Armenia ended with the Turkish conquest and with the extinction of the Bagratuni line. Little by little, numbers of Armenians withdrew into the Taurus mountains and the plateau below, but though their country rose again from ruin, it was only as a small principality in Cilicia. The fruits of Armenian civilisation — the architectural splendour of Ani, the military strength of Van, the intellectual life of Kars, the commercial pride of Bitlis and Ardzen — were no more.

Greater Armenia had been eastern rather than western, coming into contact with race after race from the east; with Byzantium alone, half eastern itself, on the west. But the civilisation of Armeno-Cilicia was western rather than eastern: its political interests were divided between Europe and Asia, and its history was overshadowed by that of the Crusades. To the Crusades the change was pre-eminently due. Crusading leaders stood in every kind of relationship to the new Armenian kingdom. They befriended and fought it by turns. They used its roads, borrowed its troops, received its embassies, fought its enemies, and established feudal governments near it. For a time their influence made it a European State, built on feudal lines, seeking agreement with the Church of Rome, and sending envoys to the principal courts of Christendom.

But the Armenian Church, which had been the inspiration and mainstay of the old civilisation, and the family ambitions, which had helped to destroy it, lived on to prove the continuity of the little State of Armeno-Cilicia with the old Bagratid kingdom.

Among the Armenian migrants to the Taurus mountains, during the invasions that followed the abdication of Gagik II, was Prince Ruben (Rupen). He had seen the assassination of Gagik to whom he was related, and he determined to avenge his kinsman's death on the Greeks. Collecting a band of companions, whose numbers increased from day to day, he took up his stand in the village of Goromozol near the fortress of Bardsrberd, drove the Greeks out of the Taurus region, and established his dominion there. The other Armenian princes recognised his supremacy and helped him to strengthen his power, though many years were to pass before the Greeks were driven out of all the Cilician towns and strongholds which they occupied.

Cilicia was divided into two well-marked districts: the plain, rich and fertile but difficult to defend, and the mountains, covered with forests and full of defiles. The wealth of the country was in its towns: Adana, Mamistra, and Anazarbus, for long the chief centres of hostility between Greeks and Armenians; Ayas with its maritime trade; Tarsus and Sis, each in turn the capital of the new Armenian State; Germanicea or Mar‘ash, and Ulnia or Zeithun. The mountainous region, difficult of approach, and sprinkled with Syrian, Greek, and Armenian monasteries, easily converted into strongholds, was the surest defence of the province, though in addition the countryside was protected by strong fortresses such as Vahka, Bardsrberd, Kapan, and Lambron.

When Ruben died, after fifteen years of wise rule (1080−1095), he was able to hand on the lordship of Cilicia to his son Constantine (1095−1100), who first brought Armeno-Cilicia into close contact with Europe. Constantine continued his father's work by capturing Vahka and other fortresses from the Greeks and thus increasing his patrimony. But he broke new ground by making an alliance with the Crusaders, who in return for his services in pointing out roads and in furnishing supplies, especially during the siege of Antioch, gave him the title of Marquess.

If the principality thus founded in hostile territory owed its existence to the energy of an Armenian prince, it owed its survival largely to external causes. In the first place, the Turks were divided. After 1092, when the Seljûq monarchy split into rival powers, Persia alone was governed by the direct Seljûq line; other sultans of Seljûq blood ruled parts of Syria and Asia Minor. Although the Sultans of Iconium or Rûm were to be a perpetual danger to Cilicia from the beginning of the twelfth century onwards, the division of the Turks at the close of the eleventh century broke for a time the force of their original advance, and gave the first Rubenians a chance to recreate the Armenian State. In the second place, the Crusades began. The Latin States founded in the East during the First Crusade checked the Turks, and also prevented the Greeks, occupied as they were with internal and external difficulties, from making a permanent reconquest of Cilicia. The Latins did not aim at protecting the Armenians, with whom indeed they often quarrelled. But as a close neighbour to a number of small states, nominally friendly but really inimical to Byzantium, Armenia was no longer isolated. Instead of being a lonely upstart principality, it became one of many recognised kingdoms, all hostile to the Greek recovery of the Levant, all entitled to the moral sanction and expecting the armed support of the mightiest kings of Europe.

For about twenty-five years after Constantine's death, his two sons, Thoros I (1100−1123) and Leo I (1123−1135), ruled the Armenians with great success. As an able administrator Thoros organised the country, and would have given his time to building churches and palaces if his enemies had left him in peace. But he had to fight both Greeks and Turks. He took Anazarbus from the Greeks and repulsed an invasion of Seljûqs and Turkomans. In his reign the death of Gagik II was at last avenged: Armenian troops seized the castle of Cyzistra and put to death the three Greek brothers who had hanged the exiled king.

{Frédéric Macler's narrative on the next nearly two and a half centuries (1130−1373) of Little Armenian (Armeno-Cilician) history omitted – Ed.}

The last King of {Little} Armenia was Leo VI of Lusignan (1373, d. 1393). His father was John, brother of King Guy, and his grandmother was Zabel, sister of Hethum II. He himself had been imprisoned with his mother Soldane of Georgia by Constantine IV, who had wished to destroy the royal Armenian line. His reign was not a success. All his efforts to avert the long-impending doom of Cilicia were powerless. He fought energetically against the Mamlûks, but was led captive to Cairo (1375). There he appointed as almoner and confessor John Dardel, whose recently-published chronicle has thrown unexpected light upon the last years of the Cilician kingdom. In 1382 the king was released and spent the rest of his life in various countries of Europe. He died in 1393 at Paris, making Richard II of England his testamentary executor, and his epitaph is still preserved in the basilica of Saint-Denis. After his death, the Kings of Cyprus were the nominal Kings of Armenia until 1489, when the title passed to Venice. Almost at the same time (1485), by reason of the marriage (1433) of Anne of Lusignan with Duke Louis I of Savoy, the rulers of Piedmont assumed the empty claim to a kingdom of the past.

During the exile of Leo VI, Greater Armenia was enduring a prolonged Tartar invasion. After conquering Baghdad (1386), Tamerlane entered Vaspurakan. At Van he caused the people to be hurled from the rock which towers above the city; at Ernjak he massacred all the inhabitants; at Sîwâs he had the Armenian garrison buried alive. In 1389 he devastated Turuberan and Taron; in 1394 he finished his campaign at Kars, where he took captive all the people whom he did not massacre, and passed on into Asia Minor. By the beginning of the fifteenth century the old Armenian territory had been divided among its Muslim conquerors — Mamlûks, Turks, and Tartars. Yûsuf, Sultan of Egypt, ruled Sassun; the Emir Erghin governed Vaspurakan from Ostan; and Tamerlane's son, Mîrân Shâh, reigned at Tabrîz. These Musulman emirs made war upon one another at the expense of the Armenian families who had not migrated to Asia Minor on the fall of the Bagratid kingdom. By the close of the fifteenth century Cilicia, too, was finally absorbed into the Ottoman Empire.

Kings and kingdom had passed, but the Armenians still possessed their Church. In the midst of desolation, schools and convents maintained Armenian art and culture, and handed on the torch of nationality. Some of the Armenian manuscripts which exist to-day were written in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The long religious controversy, of which the Uniates were the centre, survived the horrors of the period, and continued to agitate the country. Among the protagonists were John of Khrna, John of Orotn, Thomas of Medzoph, Gregory of Tathew, and Gregory of Klath. In 1438 Armenian delegates attended the Council of Florence with the Greeks and Latins in order to unify the rites and ceremonies of the Churches.

The most important work of the Church was administrative.

During Tamerlane's invasion the Katholikos had established the pontifical seat among the ruins of Sis.

But towards the middle of the next century Sis rapidly declined, and it was decided to move the seat to Echmiadzin in the old Bagratid territory.

As Grigor IX refused to leave Sis, a new Katholikos, Kirakos Virapensis, was elected for Echmiadzin, and from 1441 the Armenian Church was divided for years between those who accepted the primacy of Echmiadzin and those who were faithful to Sis.

Finally, the Katholikos of Echmiadzin became, in default of a king, the head of the Armenian people.

With his council and synod he made himself responsible for the national interests of the Armenians, and administered such possessions as remained to them.

After the Turkish victory of 1453, Mahomet II founded an Armenian colony in Constantinople and placed it under the supervision of Joakim, the Armenian Bishop of Brûsa, to whom he afterwards gave the title of “Patriarch” with jurisdiction over all the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.

From that time to this, the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople has carried on the work of the Katholikos and has been the national representative of the Armenian people.

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12

1 comments: (End)

Yeni çıkmış harika sikişlerin porno izle adresinden geçmesi daha sexi