|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: 2004-02-08 Archive

Earthdate 2004-02-14

Four years ago today — appropriately on Valentine's Day of the year 2000 — the NEAR-Shoemaker (NEAR for Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous) spacecraft slid into orbit about the asteroid 433 Eros.

The remarkable 780-frame sequence of photographs shown at left, forming a movie of Eros' stunning end-over-end rotation, was shot on 2000-02-12 (shortly before orbital insertion) at the rate of one frame every 26 seconds.

Following, and indeed preceding, arrival in Eros orbit, NEAR-Shoemaker gave the spinning mountain terrific camera coverage, providing us with close-up views of a near-Earth approaching asteroid such as we'd never seen before.

After a year of this, on 2001-02-12, the spacecraft — though never designed for any sort of landing — was commanded to settle down onto the surface of the asteroid Eros, continuing in radio contact with Earth all the while.

It sits there to this day.

Kudos to the NEAR team!

1

Four years ago today — appropriately on Valentine's Day of the year 2000 — the NEAR-Shoemaker (NEAR for Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous) spacecraft slid into orbit about the asteroid 433 Eros.

The remarkable 780-frame sequence of photographs shown at left, forming a movie of Eros' stunning end-over-end rotation, was shot on 2000-02-12 (shortly before orbital insertion) at the rate of one frame every 26 seconds.

Following, and indeed preceding, arrival in Eros orbit, NEAR-Shoemaker gave the spinning mountain terrific camera coverage, providing us with close-up views of a near-Earth approaching asteroid such as we'd never seen before.

After a year of this, on 2001-02-12, the spacecraft — though never designed for any sort of landing — was commanded to settle down onto the surface of the asteroid Eros, continuing in radio contact with Earth all the while.

It sits there to this day.

Kudos to the NEAR team!

1

UPDATE:

2004-02-24 02:00 UT:

Asteroid 433 Eros forms a 34 × 11 × 11 km (21 × 7 × 7 mile) rough cylinder, incorporating a volume of 2,503 km3 and area of 1,106 km2.

This surface area is a little larger than, say, the city of Moscow, the Dead Sea, Tahiti, or King Island in Australia, a bit smaller than Lake Champlain, Okinawa, Impearls' own Santa Cruz County in California, or the city (not county) of Los Angeles.

The rotation period (day) of Eros is 5.27 hours.

The range of surface-normal gravitational accelerations is 2.1 to 5.5 mm/s2, while the range of escape speeds is 3.1 to 17.2 m/s.

2

1 Follow this link or the one on the image above to a page with larger-scale versions of the animation. Don't miss this page of all the NEAR Eros animations, while the main NEAR page can be found here. The NEAR site's Image of the Day Archive is a particularly nice browse.

2 D. K. Yeomans, P. G. Antreasian, J.-P. Barriot, S. R. Chesley, D. W. Dunham, R. W. Farquhar, J. D. Giorgini, C. E. Helfrich, A. S. Konopliv, J. V. McAdams, J. K. Miller, W. M. Owen Jr., D. J. Scheeres, P. C. Thomas, J. Veverka, and B. G. Williams, “Radio Science Results During the NEAR-Shoemaker Spacecraft Rendezvous with Eros,” Science, Vol. 289, No. 5487 (Issue 2000-09-22), pp. 2085-2088. Requires subscription or pay-per-view.

Impearls: 2004-02-08 Archive

Earthdate 2004-02-13

There's been an altercation — a disturbance — in the fabric of the Blogosphere, whose ripplies have bounced round the tub a few times, and in further reflecting off Impearls, transformed into the form herein, “In praise of the C-Word!” featuring Geoffrey Chaucer's Wife of Bath.

There's been an altercation — a disturbance — in the fabric of the Blogosphere, whose ripplies have bounced round the tub a few times, and in further reflecting off Impearls, transformed into the form herein, “In praise of the C-Word!” featuring Geoffrey Chaucer's Wife of Bath.

I hesitate to even mention the original problem, so divergent is it from the path we're taking here, but in its first context one party took severe exception (to the extent of publicly and dramatically cutting off contact with another, a woman) over her one-time use, not directed at any specific individual, of the technical term feminazi cunt.

I shan't address the issue raised, other than express my inclination to say, “Girls, girls!” (oops, not politically correct, substitute) “Ladies, ladies! Can't you play nicely?”

I'll also not comment as to applicability of the former portion of this remarkable turn of phrase — leaving that to the girls ladies — but (now, after having offended nearly everyone) I will jump in to debate the etymological aptness of the use, at least in some contexts (appropriately in time for Valentine's Day!), of the fine old English language word “cunt” (sometimes euphemized, in modern polite company, as the c-word). How's that for a variant consequence of the original quaver in the fabric of the Blogosphere?

The c-word, it turns out (which I'll use to spare further the sensitive eared), is of venerable ancestry, dating back well into the Middle Ages, and ultimately deriving probably from an old Germanic root meaning, among other things, “a hollow space or place, an enclosing object….” Modern English words as various as cottage, codpiece, cobweb, coop, cog, cock, chicken, cudgel, kobold, and even the keel of a boat all apparently derive from this same old root. 1

Beyond illustrating this etymological history, however, I'll let Geoffrey Chaucer's character in The Canterbury Tales “The Wife of Bath” continue for me, in her own eloquent, inimitable fashion.

Happy Valentine's Day!

UPDATE: 2004-02-24 13:40 UT: Discussion continues after the quotation. Jump to Afterword.

UPDATE: 2004-03-11 16:40 UT: A follow-up article In Praise of the C-word II has been posted.

Following is an excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” in Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales: 2

|

Modern English

translated by J. U. Nicolson |

Middle English

edited by W. W. Skeat |

|---|---|

| “ ‘Of all men the most blessed may he be, | Of alle men y-blessed moot he be, |

| That wise astrologer, Dan Ptolemy, | The wyse astrologien Dan Ptholome, |

| Who says this proverb in his Almagest: | That seith this proverbe in his Almageste, |

| ”Of all men he's in wisdom the highest | “Of alle men his wisdom is the hyeste, |

| That nothing cares who has the world in hand.” | That rekketh never who hath the world in honde.” |

| By this proverb shall you understand: | By this proverbe thou shalt understonde, |

| Since you've enough, why do you reck or care | Have thou y-nogh, what that thee recche or care |

| How merrily all other folks may fare? | How merily that othere folkes fare? |

| For certainly, old dotard, by your leave, | For certeyn, old dotard, by your leve, |

| You shall have cunt all right enough at eve. | Ye shul have queynte right y-nough at eve. |

| He is too much a niggard who's so tight | He is to greet a nigard that wol werne |

| That from his lantern he'll give none a light. | A man to lighte his candle at his lanterne; |

| For he'll have never the less light, by gad; | He shal have never the lasse light, pardee; |

| Since you've enough, you need not be so sad. | Have thou y-nough, thee thar nat pleyne thee. |

| “ ‘You say, also, that if we make us gay | Thou seyst also, that if we make us gay |

| With clothing, all in costliest array, | With clothing and with precious array. |

| That it's a danger to our chastity; | That it is peril of our chastitee; |

| And you must back the saying up, pardie! | And yet, with sorwe, thou most enforce thee, |

| Repeating these words in the apostle's name: | And seye thise wordes in the apostles name, |

| “In habits meet for chastity, not shame, | “In habit, maad with chastitee and shame, |

| Your women shall be garmented,” said he, | Ye wommen shul apparaille yow,” quod he, |

| “And not with broidered hair, or jewellery, | “And noght in tressed heer and gay perree, |

| Or pearls, or gold, or costly gowns and chic”; | As perles, ne with gold, ne clothes riche”; |

| After your text and after your rubric | After thy text, ne after thy rubriche |

| I will not follow more than would a gnat. | I wol nat wirche as muchel as a gnat. |

| You said this, too, that I was like a cat; | Thou seydest this, that I was lyk a cat; |

| For if one care to singe a cat's furred skin, | For who-so wolde senge a cattes skin, |

| Then would the cat remain the house within; | Thanne wolde the cat wel dwellen in his in; |

| And if the cat's coat be all sleek and gay, | And if the cattes skin be slyk and gay, |

| She will not keep in house a half a day, | She wol nat dwelle in house half a day, |

| But out she'll go, ere dawn of any day, | But forth she wole, er any day be dawed, |

| To show her skin and caterwaul and play. | To shewe hir skin, and goon a-caterwawed; |

| This is to say, if I'm a little gay, | This is to seye, if I be gay, sir shrewe, |

| To show my rags I'll gad about all day. | I wol renne out, my borel for to shewe. |

| “ ‘Sir Ancient Fool, what ails you with your spies? | Sire olde fool, what eyleth thee to spyën? |

| Though you pray Argus, with his hundred eyes, | Thogh thou preye Argus, with his hundred yën, |

| To be my body-guard and do his best, | To be my warde-cors, as he can best, |

| Faith, he sha'n't hold me, save I am modest; | In feith, he shal nat kepe me but me lest; |

| I could delude him easily — trust me! | Yet coude I make his berd, so moot I thee. |

| “ ‘You said, also, that there are three things — three — | Thou seydest eek, that ther ben thinges three, |

| The which things are a trouble on this earth, | The whiche thinges troublen al this erthe, |

| And that no man may ever endure the fourth: | And that no wight ne may endure the ferthe: |

| O dear Sir Rogue, may Christ cut short your life! | O leve sir shrewe, Jesu shorte thy lyf! |

| Yet do you preach and say a hateful wife | Yet prechestow, and seyst, an hateful wyf |

| Is to be reckoned one of these mischances. | Y-rekened is for oon of thise meschances. |

| Are there no other kinds of resemblances | Been ther none othere maner resemblances |

| That you may liken thus your parables to, | That ye may lykne your parables to, |

| But must a hapless wife be made to do? | But-if a sely wyf be oon of tho? |

| “ ‘You liken woman's love to very Hell, | Thou lykenest wommanes love to helle, |

| To desert land where waters do not well. | To bareyne lond, ther water may not dwelle, |

| You liken it, also, unto wildfire; | Thou lyknest it also to wilde fyr; |

| The more it burns, the more it has desire | The more it brenneth, the more it hath desyr |

| To consume everything that burned may be. | To consume every thing that brent wol be. |

| You say that just as worms destroy a tree, | Thou seyst, that right as wormes shende a tree, |

| Just so a wife destroys her own husband; | Right so a wyf destroyeth hir housbonde; |

| Men know this who are bound in marriage band.’ | This knowe they that been to wyves bonde. |

| “Masters, like this, as you must understand, | Lordinges, right thus, as ye have understonde, |

| Did I my old men charge and censure, and | Bar I stifly myne olde housbondes on honde, |

| Claim that they said these things in drunkenness; | That thus they seyden in hir dronkenesse; |

| And all was false, but yet I took witness | And al was fals, but that I took witnesse |

| Of Jenkin and of my dear niece also. | On Janekin and on my nece also. |

| O Lord, the pain I gave them and the woe, | O lord, the peyne I dide hem and the wo, |

| All guiltless, too, by God's grief exquisite! | Ful giltelees, by goddes swete pyne! |

| For like a stallion could I neigh and bite. | For as an hors I coude byte and whyne. |

| I could complain, though mine was all the guilt, | I coude pleyne, thogh I were in the gilt, |

| Or else, full many a time, I'd lost the tilt. | Or elles often tyme hadde I ben spilt. |

| Whoso comes first to mill first gets meal ground; | Who-so that first to mille comth, first grint; |

| I whimpered first and so did them confound. | I pleyned first, so was our werre y-stint. |

| They were right glad to hasten to excuse | They were ful glad t'excusen hem ful blyve |

| Things they had never done, save in my ruse. | Of thing of which they never agilte hir lyve. |

| “With wenches would I charge him, by this hand, | Of wenches wolde I beren him on honde, |

| When, for some illness, he could hardly stand. | Whan that for syk unnethes mighte he stonde. |

| Yet tickled this the heart of him, for he | Yet tikled it his herte, for that he |

| Deemed it was love produced such jealousy. | Wende that I hadde of him so greet chiertee. |

| I swore that all my walking out at night | I swoor that al my walkinge out by nighte |

| Was but to spy on girls he kept outright; | Was for t'espye wenches that he dighte; |

| And under cover of that I had much mirth. | Under that colour hadde I many a mirthe. |

| For all such wit is given us at birth; | For al swich wit is yeven us in our birthe; |

| Deceit, weeping, and spinning, does God give | Deceite, weping, spinning god have yive |

| To women, naturally, the while they live. | To wommen kindely, whyl they may live. |

| And thus of one thing I speak boastfully, | And thus of o thing I avaunte me, |

| I got the best of each one, finally, | Atte ende I hadde the bettre in ech degree, |

| By trick, or force, or by some kind of thing, | By sleighte, or force, or by som maner thing, |

| As by continual growls or murmuring; | As by continuel murmur or grucching; |

| Especially in bed had they mischance, | Namely a-bedde hadden they meschaunce; |

| There would I chide and give them no pleasance; | Ther wolde I chyde and do hem no plesaunce; |

| I would no longer in the bed abide | I wolde no lenger in the bed abyde, |

| If I but felt his arm across my side, | If that I felte his arm over my syde, |

| Till he had paid his ransom unto me; | Til he had maad his raunson un-to me; |

| Then would I let him do his nicety. | Than wolde I suffre him do his nycetee. |

| And therefore to all men this tale I tell, | And ther-fore every man this tale I telle, |

| Let gain who may, for everything's to sell. | Winne who-so may, for al is for to selle. |

| With empty hand men may no falcons lure; | With empty hand men may none haukes lure; |

| For profit would I all his lust endure, | For winning wolde I al his lust endure, |

| And make for him a well-feigned appetite; | And make me a feyned appetyt; |

| Yet I in bacon never had delight; | And yet in bacon hadde I never delyt; |

| And that is why I used so much to chide. | That made me that ever I wolde hem chyde. |

| For if the pope were seated there beside | For thogh the pope had seten hem bisyde, |

| I'd not have spared them, no, at their own board. | I wolde nat spare hem at hir owene bord. |

| For by my truth, I paid them, word for word. | For by my trouthe, I quitte hem word for word. |

| So help me the True God Omnipotent, | As help me verray god omnipotent, |

| Though I right now should make my testament, | Thogh I right now sholde make my testament, |

| I owe them not a word that was not quit. | I ne owe hem nat a word that it nis quit |

| I brought it so about, and by my wit, | I broghte it so aboute by my wit, |

| That they must give it up, as for the best, | That they moste yeve it up, as for the beste; |

| Or otherwise we'd never have had rest. | Or elles hadde we never been in reste. |

| For though he glared and scowled like lion mad, | For thogh he loked as a wood leoun, |

| Yet failed he of the end he wished he had. | Yet sholde he faille of his conclusioun. |

| “Then I would say: ‘Good dearie, see you keep | Thanne wolde I seye, ‘gode lief, tak keep |

| In mind how meek is Wilkin, our old sheep; | How mekely loketh Wilkin oure sheep; |

| Come near, my spouse, come let me kiss your cheek! | Com neer, my spouse, lat me ba thy cheke! |

| You should be always patient, aye, and meek, | Ye sholde been al pacient and meke, |

| And have a sweetly scrupulous tenderness, | And han a swete spyced conscience, |

| Since you so preach of old Job's patience, yes. | Sith ye so preche of Jobes pacience. |

| Suffer always, since you so well can preach; | Suffreth alwey, sin ye so wel can preche; |

| And, save you do, be sure that we will teach | And but ye do, certein we shal yow teche |

| That it is well to leave a wife in peace. | That it is fair to have a wyf in pees. |

| One of us two must bow, to be at ease; | Oon of us two moste bowen, doutelees; |

| And since a man's more reasonable, they say, | And sith a man is more resonable |

| Than woman is, you must have patience aye. | Than womman is, ye moste been suffrable. |

| What ails you that you grumble thus and groan? | What eyleth yow to grucche thus and grone? |

| Is it because you'd have my cunt alone? | Is it for ye wolde have my queynte allone? |

| Why take it all, lo, have it every bit; | Why taak it al, lo, have it every-deel; |

| Peter! Beshrew you but you're fond of it! | Peter! I shrewe yow but ye love it weel! |

| For if I would go peddle my belle chose, | For if I wolde selle my bele chose, |

| I could walk out as fresh as is a rose; | I coude walke as fresh as is a rose; |

| But I will keep it for your own sweet tooth. | But I wol kepe it for your owene tooth, |

| You are to blame, by God I tell the truth.’ | Ye be to blame, by god, I sey yow sooth.’ |

| “Such were the words I had at my command. | Swiche maner wordes hadde we on honde. |

| Now will I tell you of my fourth husband. | Now wol I speken of my fourthe housbonde. |

| “My fourth husband, he was a reveller, | My fourthe housbonde was a revelour, |

| That is to say, he kept a paramour; | This is to seyn, he hadde a paramour; |

| And young and full of passion then was I, | And I was yong and ful of regerye, |

| Stubborn and strong and jolly as a pie. | Stiborn and strong, and joly as a pye. |

| Well could I dance to tune of harp, nor fail | Wel coude I daunce to an harpe smale, |

| To sing as well as any nightingale | And singe, y-wis, as any nightingale, |

| When I had drunk a good draught of sweet wine. | Whan I had dronke a draughte of swete wyn. |

| Metellius, the foul churl and the swine, | Metellius, the foule cherl, the swyn, |

| Did with a staff deprive his wife of life | That with a staf birafte his wyf hir lyf, |

| Because she drank wine; had I been his wife | For she drank wyn, thogh I hadde been his wyf, |

| He never should have frightened me from drink; | He sholde nat han daunted me fro drinke; |

| For after wine, of Venus must I think: | And, after wyn, on Venus moste I thinke: |

| For just as surely as cold produces hail, | For al so siker as cold engendreth hayl, |

| A liquorish mouth must have a lickerish tail. | A likerous mouth moote han a likerous tayl. |

| In women wine's no bar of impotence, | In womman vinolent is no defence, |

| This know all lechers by experience. | This knowen lechours by experience. |

| “But Lord Christ! When I do remember me | But, lord Crist! whan that it remembreth me |

| Upon my youth and on my jollity, | Up-on my yowthe, and on my jolitee, |

| It tickles me about my heart's deep root. | It tikleth me aboute myn herte rote. |

| To this day does my heart sing in salute | Unto this day it dooth myn herte bote |

| That I have had my world in my own time. | That I have had my world as in my tyme. |

| But age, alas! that poisons every prime, | But age, allas! that al wol envenyme, |

| Has taken away my beauty and my pith; | Hath me biraft my beautee and my pith; |

| Let go, farewell, the devil go therewith! | Lat go, fare-wel, the devel go therwith! |

| The flour is gone, there is no more to tell, | The flour is goon, there is na-more to telle, |

| The bran, as best I may, must I now sell; | The bren, as I best can, now moste I selle; |

| But yet to be right merry I'll try, and | But yet to be right mery wol I fonde. |

| Now will I tell you of my fourth husband.” | Now wol I tellen of my fourthe housbonde. |

| “I say that in my heart I'd great despite | I seye, I hadde in herte greet despyt |

| When he of any other had delight. | That he of any other had delyt. |

| But he was quit, by God and by Saint Joce! | But he was quit, by god and by seint Joce! |

| I made, of the same wood, a staff most gross; | I made him of the same wode a croce; |

| Not with my body and in manner foul, | Nat of my body in no foul manere, |

| But certainly I showed so gay a soul | But certeinly, I made folk swich chere, |

| That in his own thick grease I made him fry | That in his owene grece I made him frye |

| For anger and for utter jealousy. | For angre, and for verray jalousye. |

| By God, on earth I was his purgatory, | By god, in erthe I was his purgatorie, |

| For which I hope his soul lives now in glory. | For which I hope his soule be in glorie. |

| For God knows, many a time he sat and sung | For god it woot, he sat ful ofte and song |

| When the shoe bitterly his foot had wrung | Whan that his shoo ful bitterly him wrong. |

| There was no one, save God and he, that knew | Ther was no wight, save god and he, that wiste, |

| How, in so many ways, I'd twist the screw. | In many wyse, how sore I him twiste. |

| He died when I came from Jerusalem, | He deyde whan I cam fro Jerusalem, |

| And lies entombed beneath the great rood-beam, | And lyth y-grave under the rode-beem, |

| Although his tomb is not so glorious | Al is his tombe noght so curious |

| As was the sepulchre of Darius, | As was the sepulcre of him, Darius, |

| The which Apelles wrought full cleverly; | Which that Appelles wroghte subtilly; |

| 'Twas waste to bury him expensively. | It nis but wast to burie him preciously. |

| Let him fare well. God give his soul good rest, | Lat him fare-wel, god yeve his soule reste, |

| He now is in the grave and in his chest. | He is now in the grave and in his cheste. |

| “And now of my fifth husband will I tell. | Now of my fifthe housbond wol I telle. |

| God grant his soul may never get to Hell!” | God lete his soule never come in helle! |

The Wife of Bath was quite a character. There's much more terrific stuff in her Prologue: highly recommended. (I like the edition and translation of the Tales used in Britannica's Great Books of the Western World. I would note that other translations from Middle English I've seen do not translate the Middle English word queynte as its modern four-letter cognate that we've been discussing, instead substituting euphemisms such as “pudendum.”)

The question might be raised by some that 1) The Canterbury Tales were, after all, written by a man — Geoffrey Chaucer — and 2) how can a man have or should have anything at all to say about a woman's [insert c-word]?

The question might be raised by some that 1) The Canterbury Tales were, after all, written by a man — Geoffrey Chaucer — and 2) how can a man have or should have anything at all to say about a woman's [insert c-word]?

I would hope that stating the issue thus would almost answer superficial aspects of the question by itself. The c-word is unlike the n-word, say, or any ethnic word or slur sometimes used in opprobrium, in that it refers to an item of female sexual anatomy which is shared by both women and men — i.e., women's (male) lovers. (Yes, it's also shared by women's women lovers, if any, but then it's only women!) Just as blacks famously will use the (otherwise derogatory) n-word with each other — frequently affectionately, so it's been reported — so (I happen to know) male and female lovers oftentimes use the c-word in erotic banter and plain sexual discussions between themselves. As a practical matter, men have (whether women like it or not — and I'd hope, generally, they like it) a great deal to say (and do) with regard to women's c-words! Certainly, a writer can write about it.

Beyond issues of superficial nomenclature, there's the underlying question of truth in the Wife of Bath's presentation. The Canterbury Tales, of course, is a work of fiction, as well as being by a man. Nevertheless, there is such a thing as truth in art — even art, involving women characters, composed by men. In this case, it is one woman's (and her five husbands') truth — coming at us from another age to boot — but still, I would judge, there is truth to read here about people. Truth in a sense similar to what Jacob Bronowski was talking about in his slim little book The Common Sense of Science: 3

No one who stops to think about [Tolstoy's] Anna Karenina today believes that it is without morality, and that it makes no judgement on the complex actions of its heroine, her husband, and her lover. On the contrary, we find it a deeper and more moving book than a hundred conventional novels about that triangle, because it shows so much more patient, more understanding, and more heartbreaking an insight into the forces which buffet men and women. It is not a conventional book, it is a true book. And we do not mean by truth some chance correspondence with the facts in a newspaper about a despairing woman who threw herself under a train. We mean that Tolstoy understood people and events, and saw within them the interplay of personality, passion, convention, and the impact on them of the to-and-fro of outside happenings.

Thus, in my view, the Wife of Bath.

UPDATE: 2004-02-24 13:40 UT: Discussion also precedes the quotation above. Jump to Foreword.

UPDATE: 2004-03-11 16:40 UT: A follow-up article “In praise of the C-word II” has been posted.

UPDATE: 2004-04-19 14:00 UT: Geitner Simmons in his terrific Regions of Mind blog has linked to the C-word series here, commenting: “Beautiful work, as usual, by Michael McNeil of Impearls, this time offering translations of ‘The Wife of Bath's Tale’ in middle English as well as modern English. Great graphics, too. He also offers stimulating analysis of the text.”

UPDATE:

2005-07-22 20:20 UT:

Updated acknowledgment to the late Prof. Jane Zatta's Chaucer page which is now hosted at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

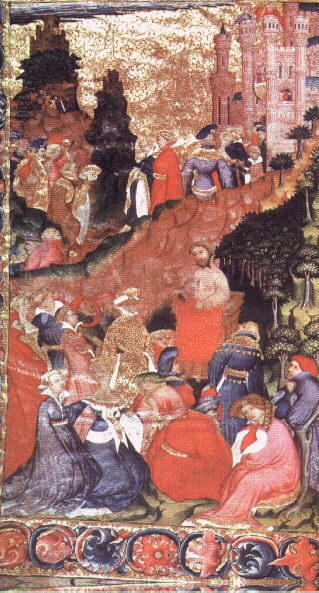

Gratitude is due Harvard and its production of

The Canterbury Tales

for the image of Chaucer's Wife of Bath, as excerpted from the Ellesmere Manuscript.

Thanks too to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for the late Prof. Jane Zatta's

Chaucer

page, including the beautiful graphic of “Geoffrey Chaucer reading from Troilus and Criseyde.”

1 “ku-”, Appendix: Indo-European Roots, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, edited by William Morris, 1969, American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc., and Houghton Mifflin Company, New York; p. 1524.

2

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1340-1400), excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue,” The Canterbury Tales, Modern English version translated by J. U. Nicolson, Middle English version edited by W. W. Skeat, Volume 22: Troilus and Cressida and The Canterbury Tales, Great Books of the Western World, 1952, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., Chicago and London;

Additional links: Various versions of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales are available online. A solely Middle English edition can be found as part of the Middle English Collection at the University of Virginia's Electronic Text Center. Librarius has a Middle English edition of the Tales, including a nice hypertext Middle English glossary. Harvard has an online edition of The Canterbury Tales with a (different than herein) dual-language presentation of the “Wife of Bath's Prologue” as part of its Geoffrey Chaucer page. Jane Zatta's Chaucer page by the late Prof. Jane Zatta at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provides good information as well as many links, including one to “The Chaucer MetaPage” (which Prof. Zatta's Chaucer page calls “an essential link to a hub of Chaucer pages”). Then there's the British Library, where Caxton's 1476 and 1483 printed editions of The Canterbury Tales may be viewed on their original pages. Finally, GeoffreyChaucer.org, presents links to other important Chaucer resources.

3

J. Bronowski, The Common Sense of Science, 1963, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.;

Impearls: 2004-02-08 Archive

Earthdate 2004-02-02

Physicist Freeman Dyson, in his book Infinite in All Directions, continues (see also Simple Tech II) his discussion of the huge impact in history of simple technologies, considering now the spinning wheel: 1

Another technology which [historian Lynn] White retrospectively assesses is the spinning wheel. The spinning wheel was a Chinese invention. The earliest documentary evidence of its existence is a Chinese painting dating from approximately A.D. 1035; it appears to have reached Europe during the thirteenth century. The spinning wheel led to a rapid expansion of European textile manufacture and to a concomitant growth of commerce. The growth was especially rapid in the linen trade. Falling prices led to an immense increase in the use of linen shirts, sheets, towels and of starched and folded linen coifs decking the heads of fashionable ladies. These were the direct consequences of the new technology. But the indirect consequences were of even greater importance. Cheap linen meant an accumulation of linen rags, and the availability of linen rags meant that paper became cheaper than parchment. By the end of the thirteenth century, the great majority of manuscripts were written on paper. There was more paper than the scribes of Europe could cover with their handwriting. The opportunity was open for an enterprising book publisher in Mainz to do away with the scribes and use machinery to put words on paper. In this way the invention of the spinning wheel opened the way for the invention of the printing press.

All these new technologies — printing, spinning, knitting, and haymaking — have become a permanent part of the fabric of modern life. There is no going back to the old ways. The voices of the victims displaced by the new technologies, the scribes displaced by Gutenberg, the old-fashioned hand spinners displaced by the spinning wheel, the forest people displaced by hay, have long been silent. We cannot measure even in retrospect the human costs and benefits of a technological revolution. We do not possess a utilitarian calculus by which to weigh the happiness and unhappiness of the people who were involved in these case histories. Technology assessment Is still an art rather than a science. As Lynn White sums up the lessons learned from his examples: “Technology assessment, if it is not to be dangerously misleading, must be based as much, if not more, on careful discussion of the imponderables in a total situation as upon the measurable elements.”

1

Freeman Dyson, Infinite in All Directions: Gifford Lectures given at Aberdeen, Scotland: April-November 1985, 1988, Harper & Row, New York; Library of Congress catalog no. Q175.3.D97 1988;

Impearls: 2004-02-08 Archive

Earthdate 2004-02-01

Physicist Freeman Dyson, in his book Infinite in All Directions, continues (see also Simple Tech I) his discussion of the impact in history of very simple technologies, using the example this time of knitting: 1

Another technology with far-reaching effects on human society is knitting. Knitting emerged later than hay but just as anonymously. The historical importance of knitting is explained in an article by Lynn White in the American Historical Review of February 1974. The title of the article is “Technology Assessment from the Stance of a Medieval Historian.” The first unequivocal evidence of knitting technology is on an altarpiece painted in the last decade of the fourteenth century, now in the Hamburg Kunsthalle. It shows the Virgin Mary knitting a shirt on four needles for the Christ Child. White collects evidence indicating that the invention of knitting made it possible for the first time to keep small children tolerably warm through the Northern winter, that the result of keeping children warm was a substantial decrease in infant mortality, that the decrease in mortality allowed parents to become emotionally more involved with their children, and that the increasing attachment of parents to children led to the appearance of the modern child-centered family. The chain of evidence linking the knitting needle with the playroom and the child psychiatrist is circumstantial but plausible. As White says at the conclusion of his analysis: “Late medieval mothers and grandmothers with clacking needles undoubtedly assessed knitting correctly as regards infant comfort and health, but that in the long run a new notion of relationships within the family would thereby be encouraged could scarcely have been foreseen.”

1

Freeman Dyson, Infinite in All Directions: Gifford Lectures given at Aberdeen, Scotland: April-November 1985, 1988, Harper & Row, New York; Library of Congress catalog no. Q175.3.D97 1988;

UPDATE: 2004-02-02 03:00 UT: Simple Tech III posted.

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12