|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

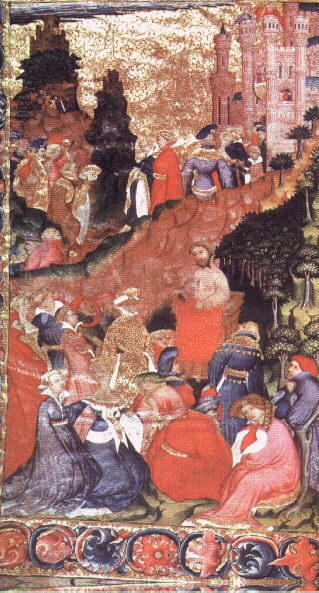

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: In praise of the C-word - Afterword

Item page — this may be a chapter or subsection of a larger work. Click on link to access entire piece.

Earthdate 2004-02-13

The Wife of Bath was quite a character. There's much more terrific stuff in her Prologue: highly recommended. (I like the edition and translation of the Tales used in Britannica's Great Books of the Western World. I would note that other translations from Middle English I've seen do not translate the Middle English word queynte as its modern four-letter cognate that we've been discussing, instead substituting euphemisms such as “pudendum.”)

The question might be raised by some that 1) The Canterbury Tales were, after all, written by a man — Geoffrey Chaucer — and 2) how can a man have or should have anything at all to say about a woman's [insert c-word]?

The question might be raised by some that 1) The Canterbury Tales were, after all, written by a man — Geoffrey Chaucer — and 2) how can a man have or should have anything at all to say about a woman's [insert c-word]?

I would hope that stating the issue thus would almost answer superficial aspects of the question by itself. The c-word is unlike the n-word, say, or any ethnic word or slur sometimes used in opprobrium, in that it refers to an item of female sexual anatomy which is shared by both women and men — i.e., women's (male) lovers. (Yes, it's also shared by women's women lovers, if any, but then it's only women!) Just as blacks famously will use the (otherwise derogatory) n-word with each other — frequently affectionately, so it's been reported — so (I happen to know) male and female lovers oftentimes use the c-word in erotic banter and plain sexual discussions between themselves. As a practical matter, men have (whether women like it or not — and I'd hope, generally, they like it) a great deal to say (and do) with regard to women's c-words! Certainly, a writer can write about it.

Beyond issues of superficial nomenclature, there's the underlying question of truth in the Wife of Bath's presentation. The Canterbury Tales, of course, is a work of fiction, as well as being by a man. Nevertheless, there is such a thing as truth in art — even art, involving women characters, composed by men. In this case, it is one woman's (and her five husbands') truth — coming at us from another age to boot — but still, I would judge, there is truth to read here about people. Truth in a sense similar to what Jacob Bronowski was talking about in his slim little book The Common Sense of Science: 3

No one who stops to think about [Tolstoy's] Anna Karenina today believes that it is without morality, and that it makes no judgement on the complex actions of its heroine, her husband, and her lover. On the contrary, we find it a deeper and more moving book than a hundred conventional novels about that triangle, because it shows so much more patient, more understanding, and more heartbreaking an insight into the forces which buffet men and women. It is not a conventional book, it is a true book. And we do not mean by truth some chance correspondence with the facts in a newspaper about a despairing woman who threw herself under a train. We mean that Tolstoy understood people and events, and saw within them the interplay of personality, passion, convention, and the impact on them of the to-and-fro of outside happenings.

Thus, in my view, the Wife of Bath.

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12