|

|

Blogroll

|

|

Most recent articles |

|

Highlights |

|

States and Economies |

|

World economies: 15 of 50 largest economies are U.S. States: |

|

World States – Table 1 |

|

History and Society |

|

Fourth of July aboard the W.W. II aircraft carrier the U.S.S. Hornet |

|

A. L. Kroeber's The Civilization of California's Far Northwest |

|

The Arab Admiralty – and an Arab naval view of the Crusades |

|

Excerpt from “The Wife of Bath's Prologue” by Geoffrey Chaucer |

|

“Horsey” Vikings: exploring origin of the “Rohirrim” in The Lord of the Rings

|

|

The Battle of Crécy by Winston S. Churchill |

|

Monotheistic Paganism, or just what was it Christianity fought and faced? |

|

Medieval constipation advice for travelers: “A ripe turd is an unbearable burden” |

|

Alexis de Tocqueville's bicentennial: Anticipatory censorship in colonial America |

|

Antiquity vs. Modernity: Alexis de Tocqueville on the mind of the slaveholder vs. soul of America |

|

Federalism, and Alexis de Tocqueville on the origins of American democracy |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Looking in the right direction – towards the future – with regard to global warming |

|

Know Your Neighborhood: from Andromeda to Fermions and Bosons |

|

Magnetars and Pulsars: Science's special section on pulsars |

|

The Geneva-Copenhagen Survey of Sun-like Stars in the Milky Way |

|

Galactic Central: the Black Hole at the Center of the Galaxy |

|

Politics and War |

|

America’s strong arm, wielding the Sword of Iraq, slays the multi-headed Hydra of Al Qaeda |

|

Regional and Personal |

|

Tamara Lynn Scott |

What wailing wight

Calls the watchman of the night?

William Blake

Whirl is king

Aristophanes

“Jumping into hyperspace ain't like dustin' crops, boy.”

Han Solo, another galaxy

|

Blogroll |

|

Grand Central Station |

|

Legal and Economic |

|

History and Society |

|

Science, Technology, Space |

|

Politics and War |

|

Eclectic |

|

Regional |

|

Reciprocal |

© Copyright 2002 – 2009

Michael Edward McNeil

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-10-12

Today is the 512th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's discovery of America, a nice round power of two which can be expressed as the number 200 hexadecimal (base 16). Nowadays Columbus's achievement has been heavily clouded by anachronistic moralizing and hackneyed “multicultural” reasoning, with the result that many people today end up quite confused as to whether Columbus achieved anything significant, or maybe was a monster to boot.

It should be clear, however, that one cannot sensibly judge other eras strictly by modern standards. That turns history into a desert, with us oh-so moral moderns suddenly leaping into ethical existence whole-cloth, as it were, out of nowhere, rather than undergoing the organic, painful accumulative growth to the modern sensibility that actually occurred.

Beyond that, people are often mystified how it's possible to “discover” a place where there are people already living. It kind of turns their heads around, thinking about it. As an American of native ancestry expressed it, writing on a private mailing list:

I don't see how any country can say they discovered America… when the Indians (different tribes) were already here. […]. This land was discovered by Indians many years before Europeans put their feet here.

The answer to this logical riddle is that prior to Columbus the human world was divided into disjoint systems of internally communicating civilizations that externally knew nothing about each other. In the Old World, the “known world” of the pre-Modern age is sometimes termed the “Oikoumene,” 1 a Greek word which basically means “inhabited universe” (it's the root from which the English “ecumenical” derives). The Old World Oikoumene as a practical matter knew zilch of the New World, neither the presence of the physical continents of America nor its vigorous native system of civilizations and peoples. Similarly, the New World's civilizations and peoples knew basically nothing of the Old. (Yes, a trickle of Siberian cultural influences reached the Eskimos of the Bering Strait, as well as their slight cultural contact with the Vikings of Greenland during that phase.)

Columbus's great achievement was to introduce the Old and New World civilizational systems to each other, “discovering America” as far as the Old World Oikoumene (known world) was concerned (attaching the two continents of America and its peoples to the formerly known world), and for the native Americans he discovered Europe-Africa-Asia (and everything within it) for them! Fundamentally, Columbus opened up the road across the Oceans, so thoroughly and completely that (unlike the formidable but transient deeds of the Vikings) the way could never be closed up again.

As if that weren't enough, not only was Columbus a master seaman — historian Samuel Eliot Morison put it, “As a master mariner and navigator, no one in the generation prior to Magellan could touch Columbus” — but he was personally responsible for the discovery of more territory (miles of land and coastline explored and surveyed) than any other explorer, including such giants as Magellan and Captain James Cook, in history.

Samuel Eliot Morison, a formidable sailor himself as well as renowned scholar, actually followed the course of Columbus's explorations in his own sailing ship. He describes Columbus's tremendous achievement in a fascinating dual-volume work The European Discovery of America: 2, 3

A glance at a map of the Caribbean may remind you of what he accomplished: discovery of the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola on the First Voyage; discovery of the Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and the south coast of Cuba on the Second, as well as founding a permanent European colony; discovery of Trinidad and the Spanish Main, on his Third; and on the Fourth Voyage, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia. No navigator in history, not even Magellan, discovered so much territory hitherto unknown to Europeans. None other so effectively translated his north-south experience under the Portuguese flag to the first east-west voyage, across the Atlantic. None other started so many things from which stem the history of the United States, of Canada, and of a score of American republics.

And do not forget that sailing west to the Orient was his idea, pursued relentlessly for six years before he had the means to try it. As a popular jingle of the 400th anniversary put it:

What if wise men as far back as Ptolemy

Judged that the earth like an orange was round,

None of them ever said, “Come along, follow me,

Sail to the West and the East will be found.”Columbus had his faults, but they were largely the defects of the qualities that made him great. These were an unbreakable faith in God and his own destiny as the bearer of the Word to lands beyond the seas; an indomitable will and stubborn persistence despite neglect, poverty, and ridicule. But there was no flaw, no dark side to the most outstanding and essential of all his qualities — seamanship. As a master mariner and navigator, no one in the generation prior to Magellan could touch Columbus. Never was a title more justly bestowed than the one which he most jealously guarded — Almirante del Mar Oceano — Admiral of the Ocean Sea.

1 Arnold Toynbee, Chapter 4: “The Oikoumenê,” Mankind and Mother Earth: A Narrative History of the World, 1976, Oxford University Press, New York; pp. 27-37 (and elsewhere in the volume).

2 Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages 1492-1616, 1974, Oxford University Press, New York; p. 267.

3 Check out Aristotle's setting the philosophical stage for Columbus's voyages across the Atlantic nearly two millennia before, which you can read about here.

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-09-11

Interesting news item, entitled “Tiny telescope takes long view to discover big planet,” from last week's Nature journal: 1

A graduate student scored a victory for the little guys last week by discovering a Jupiter-sized planet some 500 light years from Earth using a telescope just 10 centimetres [4 inches] in diameter — smaller than many amateur astronomers have in their backyards.

The discovery was made by Roi Alonso, a student at the Astrophysical Institute of the Canary Islands on Tenerife, Spain, and part of an international team running the Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES). The planet, which lies in the constellation Lyra, isn't the biggest or farthest planet yet discovered, nor the first to be detected by the transit method, which looks for a slight dip in a star's brightness as a planet passes across it. But it is the first pay-off for the TrES survey, which uses three small telescopes in the Canary Islands, Arizona and California to search 12,000 bright stars for planets. Researchers will try to confirm the existence of the planet, dubbed TrES-1, using the 10-metre Keck Telescope in Hawaii. 2

1 Nature, Vol. 431, pp. 8-9, (Issue dated 2004-09-02); doi:10.1038/431008a.

2 “TrES-1: The Transiting Planet of a Bright K0V Star,” Astrophysics, abstract, astro-ph/0408421 (dated 2004-08-23).

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-08-28

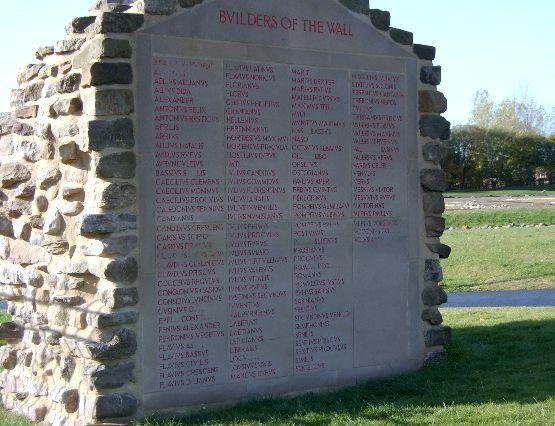

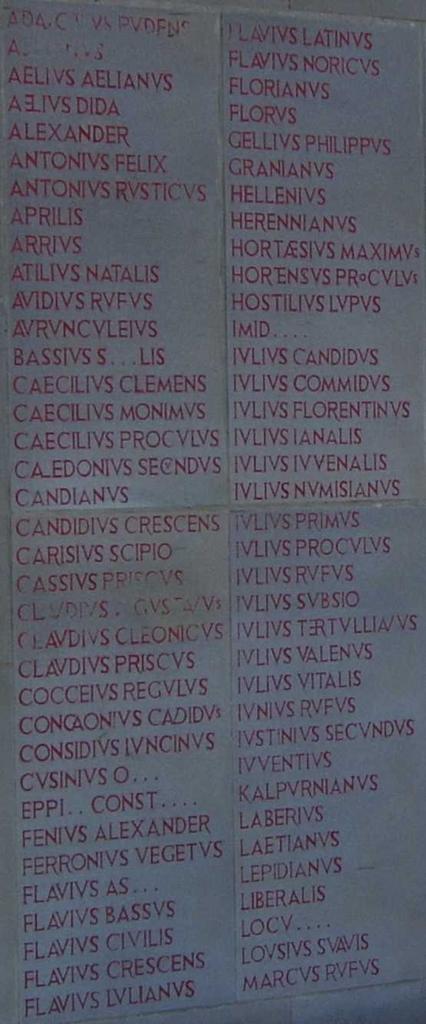

Phil Kennedy, Impearls' correspondent in the far north of England, at Wallsend, sent this photograph of a plaque commemorating the names of the builders of this portion of Hadrian's Wall, a massive complex of stone wall and fortifications erected by the Romans starting in 122 A.D. across the isthmus of northern England (the northern limit of their province of Britannia) as a barrier against the barbarians of what is now Scotland. (At the time, incidentally, the “Scots” themselves [Scoti] still lived only in Ireland.) As Phil writes:

I had nothing to do last Sunday afternoon so went to the Segedunum site (about 5 minutes walk from my front door), the end of the Wall itself (hence Wallsend, where I live), and I noticed a mock wall there with umpteen roman names. When reading the placard beside it, it said that the names were taken from a part of the wall nearby, where the names were listed as men involved in the building of the wall here — back in 122. So I got a pic or two with my camera and the names are interesting to read, and you wonder what sort of people they were. Like: Antonius Felix, Caecilius Clemens, Flavius Bassus, Julius Proculus, Valerius Flavus and so on.

Below are shown the complete list of names on a larger scale. Notice the many two-letter and even longer ligatures (beyond the “Æ” that we're still somewhat used to today) that for longer names were often used to save space in the inscription.

UPDATE: 2005-10-02 23:25 UT: Changed image hosting; minor additions to wording.

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-07-30

| Sex in Antiquity |

People nowadays have a conception of the pre-Christian era as free from the hangups about sensuality and especially sexuality that we're familiar with today, that we think began as a result of the advent of Christianity and the sexual strictures that it brought. Little could be farther from the truth in terms of attitudes during Classical Greek and Roman times towards these subjects.

We return again to that fascinating multi-volume historical series A History of Private Life, which we have had occasion to refer to here at Impearls in the past. From the title one might be inclined to think that the series is just a light-hearted, ribald catalog of sexual escapades from the past. The series scope extends across much more than that, however. Volume I, for example, titled From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, edited by Paul Veyne, includes a terrific chapter, almost 100 pages in length, delving into manifold aspects of the Roman home or domus, including detailed analysis of the architecture of various Roman homes, how the domus functioned as house and economic unit, and the manner in which “private” and “public” spaces were laid out both within it and the Roman city as a whole.

The book also considers deeply how and why the concept of the “private life” of individuals came to be distinguished from their “public life” and the consequences of that fateful division; and later on, how the barbarian invasions of the West scrambled these hard-won distinctions, turning the entire state — a res publica or “public thing,” an incomprehensible concept to the barbarians — in effect into a private estate to be exploited mercilessly by the invaders. Despite their significance and interest, we will not consider these important matters at this point; see the volumes of the series for much more on the distinguishing of “private” versus “public” in history.

In this series we will delve into that other vital aspect of “private life,” sex and, later on, its institutionalized companions, marriage and “the couple,” in classical antiquity. As Paul Veyne writes in his chapter “The Roman Empire” in Volume I: 1

[I]ncoherences and baffling limitations are found in every century. In Greco-Roman culture we find them associated with another pleasure: love. If any aspect of ancient life has been distorted by legend, this is it. It is widely but mistakenly believed that antiquity was a Garden of Eden from which repression was banished, Christianity having yet to insinuate the worm of sin into the forbidden fruit. Actually, the pagans were paralyzed by prohibitions. The legend of pagan sensuality stems from a number of traditional misinterpretations. The famous tale of the debauches of Emperor Heliogabalus is nothing but a hoax perpetrated by the literati who authored that late forgery, the Historia Augusta. The legend also stems from the crudeness of the interdictions: “Latin words are an affront to decency,” people used to say. For such naive souls, merely uttering a “bad word” provoked a shiver of perverse imagination or a gale of embarrassed laughter. Schoolboy daring.

What were the marks of the true libertine? A libertine was a man who violated three taboos: he made love before nightfall (daytime lovemaking was a privilege accorded to newlyweds on the day after the wedding); he made love without first darkening the room (the erotic poets called to witness the lamp that had shone on their pleasures); and he made love to a woman from whom he had removed every stitch of clothing (only fallen women made love without their brassieres, and paintings in Pompeii's bordellos showed even prostitutes wearing this ultimate veil). Libertines permitted themselves to touch rather than caress, though with the left hand only. The one chance a decent man had of seeing a little of his beloved's naked skin was if the moon happened to fall upon the open window at just the right moment. About libertine tyrants such as Heliogabalus, Nero, Caligula, and Domitian it was whispered that they had violated other taboos and made love with married women, well-bred maidens, freeborn adolescents, vestal virgins, or even their own sisters.

This puritanism went hand in hand with an attitude of superiority toward the love object, who was often treated like a slave. The attitude emblematic of the Roman lover was not holding his beloved by the hand or around the waist or, as in the Middle Ages, putting his arm around her neck; the woman was a servant, and the lover sprawled on top of her as though she were a sofa. The Roman way was the way of the seraglio. A small amount of sadism was permissible: a slave, for example, could be beaten in her bed, on the pretext of making her obey. The woman served her lord's pleasure and, if necessary, did all the work herself. If she straddled her passive lover, it was to serve him.

Machismo was a factor. Young men challenged one another in a macho fashion. To be active was to be a male, regardless of the sex of the passive partner. Hence there were two supreme forms of infamy: to use one's mouth to give a woman pleasure was considered servile and weak, and to allow oneself to be buggered was, for a free man, the height of passivity (impudicitia) and lack of self-respect. Pederasty was a minor sin so long as it involved relations between a free man and a slave or person of no account. Jokes about it were common among the people and in the theater, and people boasted of it in good society. Nearly anyone can enjoy sensual pleasure with a member of the same sex, and pederasty was not at all uncommon in tolerant antiquity. Many men of basically heterosexual bent used boys for sexual purposes. It was proverbially held that sex with boys procures a tranquil pleasure unruffling to the soul, whereas passion for a woman plunges a free man into unendurable slavery.

Thus, Roman love was defined by macho domination and refusal to become a slave of passion. The amorous excesses attributed to various tyrants were excesses of domination, described with misleading Sadian boldness. Nero, a tyrant who was weak more than cruel, kept a harem to serve his passive needs. Tiberius arranged for young slave boys to indulge his whims, and Messalina staged a pantomime of her own servility, usurping the male privilege of equating strength with frequency of intercourse. These acts were not so much violations as distortions of the taboos. They reflect a dreadful weakness, a need for planned pleasure. Like alcohol, lust is dangerous to virility and must not be abused. But gastronomy scarcely encourages moderation at table.

Amorous passion, the Romans believed, was particularly to be feared because it could make a free man the slave of a woman. He will call her “mistress” and, like a servant, hold her mirror or her parasol. Love was not the playground of individualists, the would-be refuge from society that it is today. Rome rejected the Greek tradition of “courtly love” of ephebes, which Romans saw as an exaltation of pure passion (in both senses of “pure,” for the Greeks pretended to believe that a man's love for a freeborn ephebe was Platonic). When a Roman fell madly in love, his friends and he himself believed either that he had lost his head from overindulgence in sensuality or that he had fallen into a state of moral slavery. The lover, like a good slave, docilely offered to die if his mistress wished it. Such excesses bore the dark magnificence of shame, and even erotic poets did not dare to glorify them openly. They chose the roundabout means of describing such behavior as an amusing reversal of the normal state of affairs, a humorous paradox.

Petrarch's praise of passion would have scandalized the ancients or made them smile. The Romans were strangers to the medieval exaltation of the beloved, an object so sublime that it remained inaccessible. They were strangers, too, to modern subjectivism, to our thirst for experience. Standing apart from the world, we choose to experience something in order to see what effect it has, not because it is intrinsically valuable or required by duty. Finally, the Romans were strangers to the real paganism, the at times graceful and beautiful paganism of the Renaissance. Tender indulgence in pleasures of the senses that became, also, delights of the soul was not the way of the ancients. The most Bacchic scenes of the Romans have nothing of the audacity of some modern writers. The Romans knew but one variety of individualism, which confirmed the rule by seeming to contradict it: energetic indolence. With secret delight they discussed senators such as Scipio, Sulla, Caesar, Petronius, and even Catiline, men scandalously indolent in private yet extraordinarily energetic in public. It was an open secret among insiders that these men were privately lazy, and such knowledge gave the senatorial elite an air of royalty and of being above the common law while confirming its authentic spirit. Although the charge of energetic indolence was a reproach, it was also somehow a compliment. Romans found this compliment reassuring. Their brand of individualism sought not real experience, self-indulgence, or private devotion, but tranquilization.

1

Paul Veyne, Chapter 1: “The Roman Empire,” Volume I: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, edited by Paul Veyne, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, A History of Private Life, the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1987;

UPDATE: 2009-09-08 17:50 UT: “Sex in Antiquity II – Moral hypochondria” and a preliminary piece “Jerangdu theories of male potency” were posted on 2005-11-05.

UPDATE: 2009-09-08 17:50 UT: “Sex in Antiquity III – the Wages of Adultery” was posted on 2009-09-06.

Labels: ancient Rome, antiquity, Paul Veyne, sex

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-07-19

Inspired by tales of Noah's flood in the Bible, people are often alert for hints that such massive flooding has occurred in the past, sometimes pointing as evidence to indistinct stories they've heard, such as the one we consider here, of great animal death scenes. A correspondent on a space exploration discussion group, as an example, writes as follows in this regard:

Many different cultures describe an “ark-like” event and a Noah-like man. There is also scientific evidence that indicates that many animals were killed and transported far from their natural habitats, as though by wild, rushing water.

I replied: I'd like to see this evidence, because it's precisely the lack of such evidence that leads science to conclude that there never was a worldwide all-embracing flood (local floods are allowed by the evidence, yes). In particular, studies of the multitudinous islands scattered round the oceans of the world show that their various organisms arrived accidentally (in very small numbers in the case of the most remote isles) by wing, by sea, or by floating objects upon it, and then evolved for millions of years (without being wiped out by floods) in total isolation, “radiating” into a spectrum of diverse living forms, filling available ecological niches that on continents would be occupied by more conventional organisms. A worldwide flood would have drowned the flora and fauna of these isolated islands, which manifestly has not occurred.

Moreover, the survival of radically different lineages of organisms (marsupials, giant birds, etc.) on remote continents such as Australia also demonstrates that no catastrophic flood followed by the dispersal of living forms from something like an “ark” ever took place.

Our correspondent then came back:

Woolly mammoths have been found almost perfectly preserved in arctic regions. They were so well preserved that their last meals had still not been digested.

Why is that significant?

1) They died so fast that they were not capable of digesting their last meal (your stomach usually continues to work if you are dying slowly of natural causes).

2) The contents of their stomachs were temperate climate vegetation — not arctic. Woolly Mammoths were not Tundra-dwellers, but that's where they were found.

These carcasses are about 12-13,000 years old.

The bodies exhibit signs of severe stress — as though they were tossed about in fast-rushing water and slammed against rocks.

There's your evidence, Mr. McNeil.

I'm afraid not, though those are very interesting cases. I've already stated that regional floods are perfectly well allowed by the geological and paleontological evidence, which is all we're talking about here. Regional floods, however massive, are a very far cry from the kind of world-embracing, topping-the-highest-mountains floods that the Noah's ark mythology conceives of.

The great volcano Mount Ararat, for example, on whose heights Noah's ark supposedly came to rest, rises to 16,864 feet (5,140 meters) above present sea level, whereas as I intimated before, oceanic island evidence proves conclusively that there has never (for many millions of years) been a flood that raised the level of the oceans by more than a few hundred feet (a hundred meters or so) above today's sea level.

On a regional basis, however, there have been some very massive floods. Probably the granddaddy of “regional” floods occurred a few million years ago when the (natural) Gibraltar dam walling off the almost dry-as-a-bone Mediterranean basin was breached by tectonic forces and the sea re-filled over a thousand years or so in a massive intrusion of seawater which remains to this day as the Mediterranean Sea. This occurred long before prehistoric and historic human times, however. See Philip and Phylis Morrison's book and PBS video series The Ring of Truth for a fascinating chapter concerning this event. 1

Other possibilities commonly cited include the filling of the Black Sea at the close of the last ice age, which did occur during prehistoric human times. This flood, though very sizable, of course falls well short of Noachian in scale, and was even smaller than one would think, since the Black Sea basin was already mostly filled by a large lake prior to the straits of the Dardanelles and Bosporus being breached by rising waters at the end of the ice age. Another example is the draining of prehistoric Lake Bonneville in what is now the western United States. Lake Bonneville was formerly a much deeper and larger lake occupying the basin in northwest Utah and northeastern Nevada that its remnant, shallow Great Salt Lake now resides in. During the ice age, erosion wore away the pass separating the Bonneville basin from the Snake River drainage in Idaho, whereupon the bulk of the lake quickly emptied itself in a huge flood down the Snake and Columbia rivers.

Considering the story of the frozen mammoths that was provided, however, the best examples of regional flooding that we can consider are the breaching of glacial lakes. The example par excellence of such flooding in the United States is the massive Columbia River (so-called “Spokane”) floods from between 15,000 and 12,800 years ago, which originated as a result of the Clark Fork River of western Montana being repeatedly dammed by an intrusion of the great Cordilleran Ice Sheet which occupied the Canadian Rockies during ice age times. As the glacier moved to block the river's exit at the present Pend Oreille Lake in northern Idaho, the Clark Fork backed up in a vast lake known as Glacial Lake Missoula until it basically filled northwestern Montana to the gills, more than 2,000 feet deep at the ice dam, and incorporating as much water, some 500 cubic miles (more than 2,000 km3), as modern Lake Ontario.

Ice, however, is a disastrous material out of which to construct a dam because ice floats, and as the lake behind the dam fills, eventually the ice dam starts to float, whereupon the vast weight of water behind it tears the dam apart and in this case emptied those 500 cubic miles of backed-up water down the Columbia River valley in as little as 48 hours, the waters roaring across eastern Washington State (a wide region known, as a result of the stupendous water erosion, as the “channeled scablands”), and leaving icebergs stranded further down the Columbia River gorge as much as 1,000 feet (300 meters) above the present river level. Think a few mammoths might have been carried off by that? Then the moving glacier would proceed to close off the Clark Fork river valley once again, and some 60 years later the whole process would repeat — over a period of thousands of years, again and again, many dozens of times. See John Eliot Allen and Marjorie Burns' Cataclysms on the Columbia for an entire book devoted to this subject. 2

Glacial lakes and associated large-scale flooding were common on the extremities of ice-age ice sheets, and the instances of frozen mammoths from Siberia that were cited are cases in point. The rivers of Siberia all run exclusively northward, which means even now that the upper courses of Siberian rivers at spring melt flow extremely vigorously while their lower reaches are still locked in ice, producing sizable floods every year. These alone are sufficient to kill herds of unwary animals, such as caribou or (if there still were any) mammoths. However, during the ice age, though the Siberian region was mostly free from ice sheet cover (a matter of the balance of precipitation vs. annual melt, not so much of cold), its rivers flowed towards the then-perpetually frozen Arctic Ocean, and on the way the waters backed up in numerous vast glacial lakes. When those lakes were breached, tremendous downstream flooding would ensue — even more capable of extinguishing life in the mass than the situation we see today.

As for the question raised of how quickly the animals died, when you're killed in a raging torrent typically you do die very quickly, no time for your stomach to digest its contents then. Moreover, since the subarctic ground, even today, is perpetually frozen in permafrost, you're then very quickly frozen, resulting in the preservation of almost fully intact corpses (not mere skeletons) of mammoths which have been discovered.

There's no need to suppose, however, that the mammoth remains in Siberia which have been found were carried to their final resting spots over any very great distances. As we saw in the case of the Glacial Lake Missoula floods, the torrent can rage for hundreds of miles, but we need not presume so for the Siberian mammoths found, nor is any extensive distance traveled required to fit the evidence. One of the intact mammoth corpses was found by the banks of Siberia's Lena River, for example, and there's no particular reason to think that it and others originated very far from where they were found.

Our correspondent asserts that “the contents of their stomachs were temperate climate vegetation — not arctic. Woolly Mammoths were not Tundra-dwellers, but that's where they were found.” On the contrary, woolly mammoths did live in the subarctic region — amidst “tundra” — throughout the ice age, but our correspondent is quite correct that the animals' stomachs contain vegetative matter that doesn't grow there today. Where he errs is presuming that what survives today on the north Siberian plain is the same as what flourished there during the ice age.

It is now believed (as a result of pollen samples and other evidence) that those huge areas maintained during the ice age a rich herbal vegetative and even grassland cover (growing atop permafrost) which supported vast herds of megafauna, much like the African savanna does today, but which plant cover subsequently retreated as a result of the profound ecological changes associated with the ending some 10,000 years ago of the age of ice, being replaced by a much poorer regime.

Thus, mammoths discovered alongside the Siberian rivers probably ate the food found in their stomachs not very far from where they died and their frozen bodies were subsequently exposed.

3,

4

UPDATE:

2004-07-23 14:50 UT:

Added reference to Morrisons' Ring of Truth.

1 Philip and Phylis Morrison, Chapter Four: “Clues,” The Ring of Truth: An Inquiry into How We Know What We Know (book and video series), Vintage Books, a division of Random House, New York, 1987; pp. 154-179.

2 John Eliot Allen and Marjorie Burns, Cataclysms on the Columbia, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, 1986.

3 Adrian M. Lister and Andrei V. Sher, “The Origin and Evolution of the Woolly Mammoth,” Science, Vol 294, Issue 5544 (issue dated 2001-11-02), pp. 1094-1097 [DOI: 10.1126/science.1056370].

4 Eske Willerslev, et al., “Diverse Plant and Animal Genetic Records from Holocene and Pleistocene Sediments,” Science, Vol 300, Issue 5620 (issue dated 2003-04-17), pp. 791-795 [DOI: 10.1126/science.1084114].

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-07-12

There's a fond recollection today enhanced by the passage of time of a uniformly enthusiastic and patriotic response to the threats of Fascism and Naziism during World War II, and a belief that everyone rushed to volunteer and there was little dissent, compared to today, during that war.

Actually, there's a lot of resemblance between attitudes among the left towards that war and this. It's worth reviewing authors from back then for insights into the controversy raging today. Following are excerpts from writings by visionary physicist Freeman Dyson and anti-utopian author George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair) (1984) in this regard.

Physicist Freeman Dyson, in his tremendously thought-provoking book Weapons and Hope, had this to say with regard to popular anticipations in Britain in advance of the Second World War: 1

By that time we had made our break with the establishment and we were fierce pacifists. We saw no hope that any acceptable future would emerge from the coming war. We had made up our minds that we would at least not be led like sheep to the slaughter as the class of 1915 had been. Our mood was no longer tragic resignation, but anger and contempt for the older generation which had brought us into this mess. We raged against the hypocrisy and stupidity of our elders, just as the young rebels raged in the 1960s in America, and for similar reasons. […]

We looked around us and saw nothing but idiocy. The great British Empire visibly crumbling, and the sooner it fell apart the better so far as we were concerned. Millions of men unemployed, and millions of children growing up undernourished in dilapidated slums. A king mouthing patriotic platitudes which none of us believed. A government which had no answer to any of its problems except to rearm as rapidly as possible. A military establishment which believed in bombing the German civilian economy as the only feasible strategy. A clique of old men in positions of power, blindly repeating the mistakes of 1914, having learned nothing and forgotten nothing in the intervening twenty-four years. A population of middle-aged nonentities, caring only for money and status, to stupid even to flee from the wrath to come.

We looked for one honest man among the political leaders of the world. Chamberlain, our prime minister, we despised as a hypocrite. Hitler was no hypocrite, but he was insane. Nobody had any use for Stalin or Mussolini. Winston Churchill was our archenemy, the man personally responsible for the Gallipoli campaign, in which so many of our six hundred died. He was the incorrigible warmonger, already planning the campaigns in which we were to die. We hated Churchill as our American successors in the 1960s hated Johnson and Nixon. But we were lucky in 1938 to find one man whom we could follow and admire, Mahatma Gandhi. […]

We had grand visions of the redemption of Europe by nonviolence. The goose-stepping soldiers, marching from country to country, meeting no resistance, finding only sullen noncooperation and six-hour lectures. The leaders of the nonviolence being shot, and others coming forward fearlessly to take their places. The goose-stepping soldiers, sickened by the cold-blooded slaughter, one day refusing to carry out the order to shoot. The massive disobedience of the soldiers disrupting the machinery of military occupation. The soldiers, converted to nonviolence, returning to their own country to use on their government the tactics that we had taught them. The final impotence of Hitler confronted with the refusal of his own soldiers to hate their enemies. The collapse of military institutions everywhere, leading to an era of worldwide peace and sanity. […]

[The lack of revolt by Hitler's troops from the cold-blooded slaughter of his concentration camps shows just how likely that dream was of coming true. When the war actually began, reality turned out to be quite different from expectations…. –Imp.]

So this was the war against which we had raged with the fury of righteous adolescence. It was all very different from what we had expected. Our gas masks, issued to the civilian population before the war began, were gathering dust in closets. Nobody spoke of anthrax bombs anymore. London was being bombed, but our streets were not choked with maimed and fear-crazed refugees. All our talk about the collapse of civilization began to seem a little irrelevant.

Mr. Churchill had now been in power for five months, and he had carried through the socialist reforms which the Labour party had failed to achieve in twenty years. War profiteers were unmercifully taxed, unemployment disappeared, and the children of the slums were for the first time adequately fed. It began to be difficult to despise Mr. Churchill as much as our principles demanded.

Our little band of pacifists was dwindling. […] Those of us who were still faithful continued to grow cabbages and boycott the OTC, but we felt less and less sure of our moral superiority. For me the final stumbling block was the establishment of the Petain-Laval government in France. This was in some sense a pacifist government. It had abandoned violent resistance to Hitler and chosen the path of reconciliation. Many of the Frenchmen who supported Petain were sincere pacifists, sharing my faith in nonviolent resistance to evil. Unfortunately, many were not. The worst of it was that there was no way to distinguish the sincere pacifists from the opportunists and collaborators. Pacifism was destroyed as a moral force as soon as Laval touched it. […]

Those of us who abandoned Gandhi and reenlisted in the OTC did not do so with any enthusiasm.

We still did not imagine that a country could fight and win a world war without destroying its soul in the process.

If anybody had told us in 1940 that England would survive six years of war against Hitler, achieve most of the political objectives for which the war had been fought, suffer only one third of the casualties we had in World War I, and finally emerge into a world in which our moral and human values were largely intact, we would have said, “No, we do not believe in fairy tales.”

1 Freeman Dyson, Weapons and Hope, 1984, Harper & Row, New York; pp. 111-113, 115-116.

Writer George Orwell wrote this poem in a letter to the Tribune during the war in response to popular pacifist attitudes in Britain in the midst of the Second World War: 1

O poet strutting from the sandbagged portal

Of that small world where barkers ply their art,

And each new “school” believes itself immortal,

Just like the horse that draws the knacker's cart:

O captain of a clique of self-advancers,

Trained in the tactics of the pamphleteer,

Where slogans serve for thoughts and sneers for answers —

You've chosen well your moment to appear

And hold your nose amid a world of horror

Like Dr Bowdler walking through Gomorrah.

In the Left Book Club days you wisely lay low,

But when “Stop Hitler!” lost its old attraction

You bounded forward in a Woolworth's halo

To cash in on anti-war reaction;

You waited till the Nazis ceased from frightening,

Then, picking a safe audience, shouted “Shame!”

Like a Prometheus you defied the lightning,

But didn't have the nerve to sign your name.

You're a true poet, but as saint and martyr

You're a mere fraud, like the Atlantic Charter.

Your hands are clean, and so were Pontius Pilate's,

But as for “bloody heads,” that's just a metaphor;

The bloody heads are on Pacific islets

Or Russian steppes or Libyan sands — it's better for

The health to be a C.O. than a fighter,

To chalk a pavement doesn't need much guts,

It pays to stay at home and be a writer

While other talents wilt in Nissen huts;

“We live like lions” — yes, just like a lion,

Pensioned on scraps in a safe cage of iron.

For while you write the warships ring you round

And flights of bombers drown the nightingales,

And every bomb that drops is worth a pound

To you or someone like you, for your sales

Are swollen with those of rivals dead or silent,

Whether in Tunis or the B.B.C.,

And in the drowsy freedom of this island

You're free to shout that England isn't free;

They even chuck you cash, as bears get buns,

For crying “Peace!” behind a screen of guns.

In 'seventeen to snub the nosing bitch

Who slipped you a white feather needed cheek,

But now, when every writer finds his niche

Within some mutual-admiration clique,

Who cares what epithets by Blimps are hurled?

Who'd give a damn if handed a white feather?

Each little mob of pansies is a world,

Cosy and warm in any kind of weather;

In such a world it's easy to “object,”

Since that's what both your friends and foes expect.

At times it's almost a more dangerous deed

Not to object; I know, for I've been bitten.

I wrote in nineteen-forty that at need

I'd fight to keep the Nazis out of Britain;

And Christ! How shocked the pinks were! Two years later

I hadn't lived it down; one had the effrontery

To write three pages calling me a “traitor,”

So black a crime it is to love one's country.

Yet where's the pink that would have thought it odd of me

To write a shelf of books in praise of sodomy?

Your game is easy, and its rules are plain:

Pretend the war began in 'thirty-nine,

Don't mention China, Ethiopia, Spain,

Don't mention Poles except to say they're swine;

Cry havoc when we bomb a German city,

When Czechs get killed don't worry in the least,

Give India a perfunctory squirt of pity

But don't inquire what happens further East;

Don't mention Jews — in short, pretend the war is

Simply a racket “got up” by the tories.

Throw in a word of “anti-Fascist” patter

From time to time, by way of reinsurance.

And then go on to prove it makes no matter

If Blimps or Nazis hold the world in durance;

And that we others who “support” the war

Are either crooks or sadists or flag-wavers

In love with drums and bugles, but still more

Concerned with cadging Brendan Bracken's favours;

Or fools who think that bombs bring back the dead.

A thing not even Harris ever said.

If you'd your way we'd leave the Russians to it

And sell our steel to Hitler as before;

Meanwhile you save your soul, and while you do it,

Take out a long-term mortgage on the war.

For after war there comes an ebb of passion,

The dead are sniggered at — and there you'll shine,

You'll be the very bull's-eye of the fashion,

You almost might get back to 'thirty-nine,

Back to the dear old game of scratch-my-neighbour

In sleek reviews financed by coolie labour.

But you don't hoot at Stalin — that's “not done” —

Only at Churchill; I've no wish to praise him,

I'd gladly shoot him when the war is won,

Or now, if there was someone to replace him.

But unlike some, I'll pay him what I owe him;

There was a time when empires crashed like houses,

And many a pink who'd titter at your poem

Was glad enough to cling to Churchill's trousers.

Christ! How they huddled up to one another

Like day-old chicks about their foster-mother!

I'm not a fan for “fighting on the beaches,”

And still less for the “breezy uplands” stuff,

I seldom listen-in to Churchill's speeches,

But I'd far sooner hear that kind of guff

Than your remark, a year or so ago,

That if the Nazis came you'd knuckle under

And peaceably “accept the status quo.”

Maybe you would! But I've a right to wonder

Which will sound better in the days to come,

“Blood, toil and sweat” or “Kiss the Nazi's bum.”

But your chief target is the radio hack,

The hire pep-talker — he's a safe objective,

Since he's unpopular and can't hit back.

It doesn't need the eye of a detective

To look down Portland Place and spot the whores,

But there are men (I grant, not the most heeded)

With twice your gifts and courage three times yours

Who do that dirty work because it's needed;

Not blindly, but for reasons they can balance,

They wear their seats out and lay waste their talents.

All propaganda's lying, yours or mine;

It's lying even when its facts are true;

That goes for Goebbels or the “party line,”

Or for the Primrose League or P.PU.

But there are truths that smaller lies can serve,

And dirtier lies that scruples can gild over;

To waste your brains on war may need more nerve

Than to dodge facts and live in mental clover;

It's mean enough when other men are dying.

But when you lie, it's much to know you're lying.

That's thirteen stanzas, and perhaps you're puzzled

To know why I've attacked you — well, here's why:

Because your enemies all are dead or muzzled.

You've never picked on one who might reply.

You've hogged the limelight and you've aired your virtue,

While chucking sops to every dangerous faction,

The Left will cheer you and the Right won't hurt you;

What did you risk? Not even a libel action.

If you would show what saintly stuff you're made of,

Why not attack the cliques you are afraid of?

Denounce Joe Stalin, jeer at the Red Army,

Insult the Pope — you'll get some come-back there;

It's honourable, even if it's barmy,

To stamp on corns all round and never care.

But for the half-way saint and cautious hero,

Whose head's unbloody even if unbowed,

My admiration's somewhere near to zero;

So my last words would be: Come off that cloud,

Unship those wings that hardly dared to flitter,

And spout your halo for a pint of bitter.

1 George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair), “As One Non-Combatant to Another (A Letter to ‘Obadiah Hornbooke’),” Tribune, 1943-06-18.

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-07-11

James Joyner in Outside the Beltway critiques a recent piece by Victor Davis Hanson on what the proper response should be to another massive terrorist attack in the U.S. on the scale or worse than 9-11. Donald Sensing in One Hand Clapping then picks up this story, commenting “James Joyner takes VDH mildly to task for what I agree is a rare lousy column on VDH's part.”

While the indicated article by Victor Davis Hanson isn't a favorite of mine (I prefer this recent piece by him frankly), still I think he's making an important point here, and much as I respect both Joyner and Sensing, I believe both are getting Hanson wrong, as well as misinterpreting history.

In the indicated piece Hanson uses the term “Shermanesque” — referring to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's invasion of Georgia and the Carolinas during the American Civil War — as inflicting “collective punishment,” as indeed it did, on these southern regions for their role in furthering the bloody War Between the States while sitting back, far behind the former battle lines, more or less fat and happy. Joyner in his reply then picks up on Hanson's phrase as somehow implying “unmeasured attack,” as he put it, perhaps even “nuking the entire Muslim world” along with “annihilat[ing] the entire populations of the Middle East.”

Now people who have read my work know I'm hardly one to argue for “unmeasured attack,” or “annihilating the entire populations of the Middle East” — quite the reverse. From what I can see, however, Hanson's article does not argue for any of that.

In fact, Hanson says nothing in his piece about killing on a vast scale in response to a large-scale terrorist attack, and moreover it's really a slur on William Tecumseh Sherman and what he accomplished during the American Civil War to imply that his invasion of the South massacred whole populations or even small portions thereof. Yes, Gen. Sherman's army did destroy troop concentrations which tried to oppose it, and went on to deliberately demolish much civilian and public property, engendering (as Joyner pointed out) long-lasting “regional enmity.”

Nevertheless, murder was left out of the equation. Here's what Winston Churchill (yes, that Churchill) had to say about it in his superb History of the English-Speaking Peoples (which has an excellent section on the U.S. Civil War by the way): 1

Georgia was full of food in this dark winter. Sherman set himself to march through it on a wide front, living on the country, devouring and destroying all farms, villages, towns, railroads, and public works which lay within his wide-ranging reach. He left behind him a blackened trail, and hatreds which pursue his memory to this day. “War is hell,” he said, and certainly he made it so. But no one must suppose that his depredations and pillage were comparable to the atrocities which were committed during the World Wars of the twentieth century or the barbarities of the Middle Ages. Searching investigation has discovered hardly a case of murder or rape.

Thus, though Sherman destroyed much property (and earned lasting hatred from southerners as a result), the nearly total lack of civilian casualties is a remarkable humanitarian record and achievement — one must note amidst the carnage of the bloodiest war (out of one-tenth the present population) in U.S. history — not an example of “unmeasured attack,” certainly not the equivalent of “nuking the entire Muslim world.”

Victor Davis Hanson is a historian, and surely is aware of this detail about Sherman's campaign — even if much of the public (especially the South of the U.S.) has built up this myth of Sherman's “atrocities.”

In my view, that's what Hanson is advocating here: communicating to the supporters of terrorism that “War is Hell” without invoking wanton massacre.

As he writes in the subject piece, “Perhaps it would be best to inform hostile countries right now of a (big) list of their assets — military bases, power plants, communications, and assorted infrastructure — that will be taken out in the aftermath of another attack, a detailed sequence of targets that will be activated when the culpable terrorists' bases and support networks are identified and confirmed.”

Culprit regimes should “anticipate the consequences should another 3,000 Americans be incinerated at work.”

That doesn't sound like massacre to me, and as Hanson points out, could well help prevent another massacre — of Americans.

1 Winston S. Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Four: The Great Democracies, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York, 1958, pp. 258-259.

Impearls: 2004-10-10 Archive

Earthdate 2004-06-26

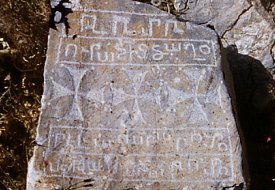

| Greater Armenia |

Joel in his intriguing Far Outliers blog, which we've had occasion to mention before here at Impearls, has been quoting from Robert D. Kaplan's year 2000 book Eastward to Tartary: Travels in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the Caucasus, providing fascinating glimpses of Armenia, Trabzon (the medieval Byzantine city of Trebizond) and other formerly Armenian-populated portions of present day Turkey, as well as of Azerbaijan.

Our only disappointment is that Kaplan provides too scanty a view of Armenian history, most particularly the medieval period when Greater Armenia, including far more than the present Armenian Republic, was in its heyday. To remedy this drawback Impearls proceeds to reveal its own look at medieval Armenian history, drawing from a now public-domain chapter in the first edition of the renowned Cambridge Medieval History, by early twentieth century French scholar of Armenia Frédéric Macler (1869-1938), Professor of Armenian for many years at the École nationale des Langues orientales vivantes, Paris. 1

We will also make frequent reference to the splendid pictorial “VirtualAni” site, which folks definitely ought not miss.

Following is an index of the parts into which Frédéric Macler's chapter “Armenia” has been divided:

Greater Armenia→ Introduction

→ The Arab Conquest

→ Recovery and Independence

→ The Arabs return, but are driven out

→ (Mostly) Peace and prosperity

→ Greeks and Turks

→ Little Armenia and Aftermath

→ Acknowledgments and References

→ (End)

UPDATE: 2004-07-03 17:50 UT: Corrected a few typos; modified photograph usage at the request of VirtualAni.

UPDATE: 2004-07-13 14:00 UT: Joel at Far Outliers, whose posting inspired this whole thing, has linked back to this article (under the title “Greater Armenia Impearled”) with lengthy quotations and the comment, “To add depth to the brief mentions of Armenia on this blog and elsewhere, the wonderfully informative Impearls ‘proceeds to reveal its own look at medieval Armenian history […].’ I'll post just a few paragraphs from each part. Visit Impearls for the rest, plus illustrations, maps, notes, and acknowledgments.”

Jakub at a site called Social Bookmarks has linked to this piece, under the title “Medieval Armenia.”

Nathan at an interesting blog I hadn't previously been aware of called The Argus, devoted as it says to “watching Central Asia and the Caucasus,” linked to this article, commenting “The extent of my what I can say I definitely know about Armenia is its location and that it has a long and fascinating history. Joel points to a series of posts from Impearls on Medieval Armenia. Don't miss it!”

Matt at another blog new to me called Blogrel (which I'd thought was a cute bloggish pun on “doggerel,” but is actually a union of “blog” plus the word grel meaning “to write” in Armenian) then linked to the piece, adding: “Impearls has a detailed post about Greater Armenia (Via The Argus). It's an ‘all you ever wanted to know about historical Armenia but were afraid to ask.’ […] This is a novel use of a blog. A blog about history. One thing is I don't see any way to make comments, but maybe that's a good idea. Make sure you have a good cup of haykakan surtch and read the full post.”

Last but not least, Geitner Simmons at his wide-ranging Regions of Mind blog, has linked to the Armenia piece (along with our Northwestern California article) with the comment: “Michael McNeil continues to demonstrate creativity at his blog Impearls. Michael has put together a spectacular package about early Armenian history. In another post, he examines some aspects of natural history in California's Klamath Mountains. The graphics are first-rate — a wide range of architectural and cultural images involving Armenia, plus a terrific satellite photo and mountain images in regard to northwestern California. Michael's look at Armenia underscores the devastation and brutality involved as warring empires and kingdoms struggled for control.” Geitner illustrates with his own striking photo of a structure dating from early medieval Armenia.

UPDATE: 2009-11-09 13:10 UT: Updated to fix broken picture links, and a couple of lingering typos.

Labels: ancient Rome, antiquity, Arab civilization, Armenia, Byzantium, medieval

| Introduction by Frédéric Macler |

Lying across the chief meeting-place of Europe and Asia, Armenia suffered immeasurably more from the conflict of two civilisations than it profited by their exchange of goods and ideas. If the West penetrated the East under pressure from Rome, Byzantium, or crusading Europe, if the East moved westwards, under Persian, Arab, Mongol, or Turk, the roads used were too often the roads of Armenia.

This was not all. East and West claimed and fought for control or possession of the country. Divided bodily between Rome and Persia in pre-Christian times, an apple of discord between Persia and the Byzantine Empire during the early part of the Middle Ages, Armenia for the rest of its national history was alternately the prey of Eastern and Western peoples. When the Armenian kingdom was strong enough to choose its own friends, it turned sometimes to the East, sometimes to the West. It drew its culture from both. But, belonging wholly neither to West nor to East, it suffered consistently at the hands of each in turn and of both together.

The stubborn pride of the Armenians in their national Church prevented them from uniting permanently either with Christendom or with Islâm. Though driven by eastern pressure as far west as Cilicia, where it was in touch with the Crusaders, Armenia never held more than a doubtful place in the state-system of medieval Europe. Sooner than sink their identity in Greek or Roman Church, the Armenians more than once chose the friendship of infidels. On the other hand, whether as neighbours or as enemies, as allies or as conquerors, the races of the East could never turn the Armenians from their faith. When Armenia ceased to exist as a State, its people kept alive their nationality in their Church. As with the Jews, their ecclesiastical obstinacy was at once their danger and their strength: it left them friendless, but it enabled them to survive political extinction.

Isolated by religion, Armenia was also perpetually divided against itself by its rival princes. Like the Church, the numerous princely houses both preserved and weakened their country. They prevented the foundation of a unified national State. But a large Power stretching perhaps from Cappadocia to the Caspian borders, and disabled by ill-defined frontiers, could never have outfaced the hostility of Europe and Asia. A collection of small principalities, grouped round rocky strongholds difficult of access, had always, even after wholesale conquest, a latent faculty of recovery in the energy of its powerful families. The Arabs could have destroyed a single royal line, but, slaughter as they might, Armenia was never leaderless: they could not exterminate its nobility. The political history of Armenia, especially during the first half of the Middle Ages, is a history of great families. And this helps to explain the puzzling movement of Armenian boundaries — a movement due not only to pressure from outside, but also to the short-lived uprising, first of one prince, then of another, amidst the ruin, widespread and repeated, of his country.

During the triumph of Rome and for many generations of Rome's decline Armenia was ruled by a national dynasty related to the Arsacidae, kings of Parthia (b.c. 149 − a.d. 428). The country had been for many years a victim to the wars and diplomacy of Persia and Rome when in a.d. 386−7 it was partitioned by Sapor III and the Emperor Theodosius. From 387 to 428 the Arsacid kings of Armenia were vassals of Persia, while the westernmost part of their kingdom was incorporated in the Roman Empire and ruled by a count.

The history of the thousand years that followed (428−1473) is sketched in this chapter. {Note: except for consideration of an aftermath of the medieval period, in the more detailed sketch below we end soon after the start of the twelfth century – Ed.} It may be divided into five distinct periods. First came long years of anarchy, during which Armenia had no independent existence but was the prey of Persians, Greeks, and Arabs (428−885). Four and a half centuries of foreign domination were then succeeded by nearly two centuries of autonomy. During this second period Armenia was ruled from Transcaucasia by the national dynasty of the Bagratuni. After 1046, when the Bagratid kingdom was conquered by the Greeks, who were soon dispossessed by the Turks, Greater Armenia never recovered its political life.

Meanwhile the third period of Armenia's medieval history had opened in Asia Minor, where a new Armenian State was founded in Cilicia by Prince Ruben, a kinsman of the Bagratuni. From 1080−1340 Rubenian and Hethumian princes ruled Armeno-Cilicia, first as lords or barons (1080−1198), then as kings (1198−1342). During this period the Armenians engaged in a successful struggle with the Greeks, and in a prolonged and losing contest with the Seljûqs and Mamlûks. Throughout these years the relations between the Armenian rulers and the Latin kingdoms of Syria were so close that up to a point the history of Armeno-Cilicia may be considered merely as an episode in the history of the Crusades. This view is strengthened by the events of the fourth period (1342−1373), during which Cilicia was ruled by the crusading family of the Lusignans. When the Lusignan dynasty was overthrown by the Mamlûks in 1375, the Armenians lost their political existence once more. In the fifth and last period of their medieval history (1375−1473), they suffered the horrors of a Tartar invasion under Tamerlane and finally passed under the yoke of the Ottoman Turks.

| The Arab Conquest by Frédéric Macler |

When Ardashes, the last Arsacid vassal-king, was deposed in 428, Armenia was governed directly by the Persians, who already partly controlled the country. No strict chronology has yet been fixed for the centuries of anarchy which ensued (428−885), but it appears that Persian rule lasted for about two centuries (428−633). Byzantine rule followed, spreading eastward from Roman Armenia, and after two generations (633−693) the Arabs replaced the Greeks and held the Armenians in subjection until 862.

In this long period of foreign rule, the Armenians invariably found a change of masters a change for the worse. The Persians ruled the country th{r}ough a succession of Marzpans, or military commanders of the frontiers, who also had to keep order and to collect revenue. With a strong guard under their own command, they did not destroy the old national militia nor take away the privileges of the nobility, and at first they allowed full liberty to the Katholikos and his bishops. As long as the Persians governed with such tolerance, they might fairly hope to fuse the Armenian nation with their own. But a change of religious policy under Yezdegerd II and Piroz roused the Armenians to defend their faith in a serious of religious wars lasting until the end of the sixth century, during which Vardan with his 1036 companions perished for the Christian faith in the terrible battle of Avaraïr (454). But, whether defeated or victorious, the Armenians never exchanged their Christianity for Zoroastrianism.

On the whole, the Marzpans ruled Armenia as well as they could. In spite of the religious persecution and of a dispute about the Council of Chalcedon between the Armenians and their fellow-Christians in Georgia, the Armenian Church more than held its ground, and ruined churches and monasteries were restored or rebuilt towards the opening of the seventh century. Of the later Marzpans some bore Armenian names. The last of them belonged to the Bagratuni family which was destined to sustain the national existence of Armenia for many generations against untold odds. But this gleam of hope was extinguished by the fall of the Persian Empire before the Arabs. For when they conquered Persia, Armenia turned to Byzantium, and was ruled for sixty years by officials who received the rank of Curopalates and were appointed by the Emperor (633−693). The Curopalates, it appears, was entrusted with the civil administration of the country, while the military command was held by an Armenian General of the Forces.

Though the Curopalates, too, seems to have been always Armenian, the despotic yoke of the Greeks was even harder to bear than the burden of religious wars imposed by the Persians. If the Persians had tried to make the Armenians worship the Sacred Fire, the Greeks were equally bent on forcing them to renounce the Eutychian heresy. As usual, the Armenians refused to yield. The Emperor Constantine came himself to Armenia in 647, but his visit did nothing to strengthen Byzantine authority. The advance of the Arabs, who had begun to invade Armenia ten years earlier under ‘Abd-ar-Rahîm, made stable government impossible, for, sooner than merge themselves in the Greek Church, the Armenians sought Muslim protection. But the Arabs exacted so heavy a tribute that Armenia turned again to the Eastern Empire. As a result, the Armenians suffered equally from Greeks and Arabs. When they paid tribute to the Arabs, the Greeks invaded and devastated their land. When they turned to the Greeks, the Arabs punished their success and failure alike by invasion and rapine. Finally, at the close of the seventh century, the Armenian people submitted absolutely to the Caliphate. The Curopalates had fled, the General of the Forces and the Patriarch (Katholikos) Sahak IV were prisoners in Damascus, and some of the Armenian princes had been tortured and put to death.

A period of unqualified tyranny followed. The Arabs intended to rivet the chains of abject submission upon Armenia, and to extort from its helplessness the greatest possible amount of revenue. Ostikans, or governors, foreigners almost without exception, ruled the country for Baghdad. These officials commanded an army, and were supposed to collect the taxes and to keep the people submissive. They loaded Armenia with heavy imposts, and tried to destroy the princely families by imprisoning and killing their men and confiscating their possessions. Under such treatment the Armenians were occasionally cowed but usually rebellious. Their national existence, manifest in rebellion, was upheld by the princes. First one, then another, revolted against the Muslims, made overtures to the enemies of Baghdad, and aspired to re-found the kingdom of Armenia.

Shortly after the Arab conquest, the Armenians turned once more to their old masters, the Greeks. With the help of Leo the Isaurian, Smbat (Sempad) Bagratuni defeated the Arabs, and was commissioned to rule Armenia by the Emperor. But after a severe struggle the Muslims regained their dominion, and sent the Arab commander Qâsim to punish the Armenians (704). He carried out his task with oriental ferocity. He set fire to the church of Nakhijevan, into which he had driven the princes and nobles, and then pillaged the country and sent many of the people into captivity.

These savage reprisals were typical of Arab misrule for the next forty years, and after a peaceful interval during which a friendly Ostikan, Marwân, entrusted the government of Armenia to Ashot Bagratuni, the reign of terror started afresh (758). But, in defiance of extortion and cruelty, insurrection followed insurrection. Local revolts, led now by one prince, now by another, broke out. On one occasion Mushegh Mamikonian drove the Ostikan out of Dwin, but the Armenians paid dear for their success. The Arabs marched against them 30,000 strong; Mushegh fell in battle, and the other princes fled into strongholds (780). Though in 786, when Hârûn ar-Rashîd was Caliph, the country was for the time subdued, alliances between Persian and Armenian princes twice ripened into open rebellion in the first half of the ninth century. The Arabs punished the second of these unsuccessful rebellions by wholesale pillage and by torture, captivity, and death (c. 850).

| Recovery and Independence by Frédéric Macler |

As the long period of gloom, faintly starred by calamitous victories, passed into the ninth century, the Arab oppression slowly lightened. The Abbasid Empire was drawing to its fall. While the Arabs were facing their own troubles, the Armenian nobility were founding principalities. The Mamikonian family, it is true, died out in the middle of the ninth century without founding a kingdom. Yet, because they had no wide territories, they served Armenia disinterestedly, and though of foreign origin could claim many of the national heroes of their adopted country: Vasak, Mushegh, and Manuel, three generals of the Christian Arsacidae; Vardan, who died for the faith in the religious wars; Vahan the Wolf and Vahan Kamsarakan, who fought the Persians; David, Grigor, and Mushegh, rebels against Arab misrule. The Arcruni and the Siwni, who had also defended Armenia against the Arabs, founded independent states in the tenth century. The Arcruni established their kingdom (Vaspurakan) round the rocky citadel of Van, overlooking Lake Van (908). Later, two different branches of their family founded the two states of the Reshtuni and the Antsevatsi. The Siwni kingdom (Siunia) arose in the latter half of the century (970). Many other principalities were also formed, each claiming independence, the largest and most important of them all being the kingdom of the Bagratuni.

Like the Mamikonians, the Bagratuni seem to have come from abroad. According to Moses of Chorene, they were brought to Armenia from Judaea by Hratchea, son of Paroïr, in b.c. 600. In the time of the Parthians, King Valarsaces gave to Bagarat the hereditary honour of placing the crown upon the head of the Armenian king, and for centuries afterwards Bagarat's family gave leaders to the Armenians. Varaztirots Bagratuni was the last Marzpan of the Persian domination, and the third Curopalates of Armenia under the Byzantine Empire. Ashot (Ashod) Bagratuni seized the government when the Arabs were trying to dislodge the Greeks in the middle of the seventh century, and foreshadowed the later policy of his family by his friendliness towards the Caliph, to whom he paid tribute. He fell in battle, resisting the Greeks sent by Justinian II. Smbat Bagratuni, made general of the forces by Justinian, favoured the Greeks. Escaping from captivity in Damascus, it was he who had defeated the Arabs with the help of Leo the Isaurian, and governed the Armenians from the fortresses of Taïkh. In the middle of the eighth century, another Ashot reverted to the policy of his namesake, and was allowed by Marwân, the friendly Ostikan, to rule Armenia as “Prince of Princes.” In consequence he refused to rebel with other Armenian princes when the Arab tyranny was renewed, and for his loyalty was blinded by his compatriots. Of his successors, some fought against the Arabs and some sought their friendship; Bagratuni princes took a leading part on both sides in the Armeno-Persian rebellions suppressed by the Arabs in the first half of the ninth century.

The Bagratuni were also wealthy. Unlike the Mamikonians, they owned vast territories, and founded a strong principality in the country of Ararat. Their wealth, their lands, and their history made them the most powerful of Armenian families and pointed out to them a future more memorable than their past. Midway in the ninth century, the power of the Bagratuni was inherited by Prince Ashot. The son of Smbat the Confessor, he refounded the ancient kingdom of Armenia and gave it a dynasty of two centuries' duration. Under the rule of the Bagratuni kings Armenia passed through the most national phase of its history. It was a conquered province before they rose to power, it became more European and less Armenian after their line was extinct. Like Ashot himself, his descendants tried at first to control the whole of Armenia, but from 928 onwards they were obliged to content themselves with real dominion in their hereditary lands and moral supremacy over the other princes. This second and more peaceful period of their rule was the very summer of Armenian civilisation.

Ashot had come into a great inheritance. In addition to the provinces of Ararat and Taïkh, he owned Gugarkh and Turuberan, large properties in higher Armenia, as well as the towns of Bagaran, Mush, Kolb, and Kars with all their territory. He could put into the field an army of forty thousand men, and by giving his daughters in marriage to the princes of the Arcruni and the Siwni he made friends of two possible rivals. For many years his chief desire was to pacify Armenia and to restore the wasted districts, and at the same time to earn the favour of the Caliphate. In return, the Arabs called him “Prince of Princes” (859) and sent home their Armenian prisoners. Two years later Ashot and his brother routed an army, double the size of their own, led into Armenia by Shahap, a Persian who was aiming at independence. Ashot's politic loyalty to the Arabs finally moved the Caliph Mu‘tamid to make him King of Armenia (885−7), and at the same time he likewise received a crown and royal gifts from the Byzantine Emperor, Basil the Macedonian. But Armenia was not even yet entirely freed from Arab control. Tribute was paid to Baghdad not immediately but through the neighbouring Ostikan of Azerbâ’îjân, and the coronation of Armenian kings waited upon the approval of the Caliphs.

During his brief reign of five years, Ashot I revived many of the customs of the old Arsacid kingdom which had perished four and a half centuries earlier. The crown, it seems, was handed down according to the principle of primogeniture. The kings, though nearly always active soldiers themselves, do not appear to have held the supreme military command, which they usually entrusted to a “general of the forces,” an ancient office once hereditary in the Mamikonian family, but in later times often filled by a brother of the reigning king. In Ashot's time, for instance, his brother Abas was generalissimo, and after Ashot's death was succeeded by a younger brother of the new king.

The Katholikos was, after the king, the most important person in Armenia. He had been the only national representative of the Armenians during the period of anarchy when they had no king, and his office had been respected by the Persians and used by the Arabs as a medium of negotiation with the Armenian princes. Under the Bagratid kings, the Katholikos nearly always worked with the monarchy, whose representatives it was his privilege to anoint. He would press coronation upon a reluctant king, would mediate between kings and their rebellious subjects, would lay the king's needs before the Byzantine court, or would be entrusted with the keys of the Armenian capital in the king's absence. Sometimes in supporting the monarchy he would oppose the people's will, especially in a later period, when, long after the fall of the Bagratuni dynasty, King and Katholikos worked together for religious union with Rome against the bitter hostility of their subjects.

Ashot made good use of every interval of peace by restoring the commerce, industry, and agriculture of his country, and by re-populating hundreds of towns and villages. For the sake of peace he made alliances with most of the neighbouring kings and princes, and after travelling through his own estates and through Little Armenia, he went to Constantinople to see the Emperor Leo the Philosopher, himself reputedly an Armenian by descent. The two monarchs signed a political and commercial treaty, and Ashot gave the Emperor an Armenian contingent to help him against the Bulgarians.

Ashot died on the journey home, and his body was carried to Bagaran, the old city of idols, and the seat of his new-formed power. But long before his death, his country's peace, diligently cherished for a life-time, had been broken by the Armenians themselves. One after another, various localities, including Vanand and Gugarkh, had revolted, and although Ashot had been able to restore order everywhere, such disturbances promised ill for the future. The proud ambition of these Armenian princes had breathed a fitful life into a conquered province only to sap the vitality of an autonomous kingdom.

| (Blank last screen) |

|

2002-11-03 2002-11-10 2002-11-17 2002-11-24 2002-12-01 2002-12-08 2002-12-15 2002-12-22 2002-12-29 2003-01-05 2003-01-12 2003-01-19 2003-01-26 2003-02-02 2003-02-16 2003-04-20 2003-04-27 2003-05-04 2003-05-11 2003-06-01 2003-06-15 2003-06-22 2003-06-29 2003-07-13 2003-07-20 2003-08-03 2003-08-10 2003-08-24 2003-08-31 2003-09-07 2003-09-28 2003-10-05 2003-10-26 2003-11-02 2003-11-16 2003-11-23 2003-11-30 2003-12-07 2003-12-14 2003-12-21 2003-12-28 2004-01-04 2004-01-11 2004-01-25 2004-02-01 2004-02-08 2004-02-29 2004-03-07 2004-03-14 2004-03-21 2004-03-28 2004-04-04 2004-04-11 2004-04-18 2004-04-25 2004-05-02 2004-05-16 2004-05-23 2004-05-30 2004-06-06 2004-06-13 2004-06-20 2004-07-11 2004-07-18 2004-07-25 2004-08-22 2004-09-05 2004-10-10 2005-06-12 2005-06-19 2005-06-26 2005-07-03 2005-07-10 2005-07-24 2005-08-07 2005-08-21 2005-08-28 2005-09-04 2005-09-11 2005-09-18 2005-10-02 2005-10-09 2005-10-16 2005-10-30 2005-11-06 2005-11-27 2006-04-02 2006-04-09 2006-07-02 2006-07-23 2006-07-30 2007-01-21 2007-02-04 2007-04-22 2007-05-13 2007-06-17 2007-09-09 2007-09-16 2007-09-23 2007-10-07 2007-10-21 2007-11-04 2009-06-28 2009-07-19 2009-08-23 2009-09-06 2009-09-20 2009-12-13 2011-03-27 2012-01-01 2012-02-05 2012-02-12